Editor’s note: Eric Gordon is translating several fictional works written by Portuguese Communist Party leader Álvaro Cunhal under the pseudonym Manuel Tiago. The Six-Pointed Star is the second in what is hoped to be a series of works put out in English for the first time by International Publishers. Below is an interview between People’s World and Gordon.

C.J. Atkins: Nice to sit down with you again. When we talked last, it was about the first of the Manuel Tiago works of fiction that you translated, Five Days, Five Nights. Now International Publishers has issued The Six-Pointed Star. So this project is well under way now.

Eric A. Gordon: Yes, it is, book two out of a projected eight. These interviews could become habit-forming!

Atkins: And how’s it going?

Gordon: It appears the first book did pretty well in terms of sales. How do I know? I don’t have their actual sales numbers, but for several weeks International Publishers (IP) had it on their list of their three top-selling items. There were a few reviews—an excellent one in People’s World, thank you!—and I got quite a lot of favorable reader comments from friends. We started with that book because the Portuguese publishers felt that it had always been one of their most popular titles and should find an equally receptive audience here in the U.S.

We don’t have a grand scheme for the rest of the series. I’m just taking them one at a time, not even in chronological order by original date of publication. In the long run, when they’re all available, I don’t think the order will matter much. I’m saving the 500-page epic novel Until Tomorrow, Comrades for last, by which time I should be really steeped in his style.

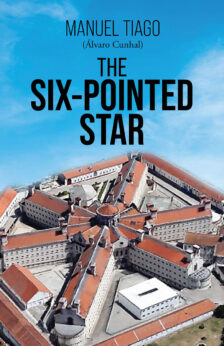

The Six-Pointed Star was first published in 1994. When I saw the title I imagined it might be about the quasi-underground community of clandestine Jews in Portugal, but of course, I was way off. As the cover so powerfully shows, it’s about a prison with six wings emanating from a central rotunda.

Atkins: As we’ve talked about before, Manuel Tiago was the pen named used by Álvaro Cunhal, the longtime leader of the Portuguese Communist Party. Did he base this book on personal experiences?

Gordon: He sure did! Cunhal himself spent 11 years in the Portuguese prison system for his Communist activism and leadership. It’s very clear he derived much of his raw material about prison life from his years in the clutches of the Portuguese fascist state, and from other actual cases he knew about. There’s mention in the book of a Communist prisoner who dies of starvation, but that is the actual story of Militão Ribeiro, who died in the Lisbon Penitentiary on Jan. 2, 1950, weighing just 37 kilos (81.5 lbs.). Most of the characters depicted in this novel, however, had been convicted for other types of crimes—violent, mostly—not typically fitting the profile of a political prisoner.

Cunhal spent over seven years in that same six-pointed Lisbon Penitentiary from 1949 to 1956. He was kept incommunicado for 14 months, and that experience, in particular, is recapitulated in the novel. Later, due to his poor health, he was transferred to the infirmary. The conditions being less harsh, it was here that he came to know some of the hundreds of common prisoners he fictionally describes in the novel.

In 1956, Cunhal was transferred to the Fort of Peniche, from which he escaped, with nine other comrades, on Jan. 3, 1960—one of the most spectacular and daring escapes in the history of the world communist movement. Formally, his prison term was already over. But he had also been condemned to arbitrary “security measures,” which allowed for successive indefinite extensions at the will of the PIDE, the political police. It’s interesting to note the date of that escape—ten years and one day after the death of Militão Ribeiro. Possibly an homage to him?

Atkins: There is a substantial body of prison literature, much of it quite political. I’m thinking of Alexander Berkman’s Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, the South African play The Island by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona, based on the notorious Robben Island prison where Nelson Mandela was held for 27 years. There’s Men in Prison by Victor Serge, Dario Fo’s play Accidental Death of an Anarchist, and of course, I’d be remiss to forget The Gulag Archipelago by Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and lots more, I know. Where does The Six-Pointed Star fit into this catalog?

Gordon: Prisons are pretty ugly and arbitrary places wherever they are, and this book shows that applies to fascist Portugal as well. My original thinking was that the title alone might suggest that Jewish theme to other readers as well, so I was considering giving the book a subtitle: “Inside and Outside a Portuguese Fascist Prison.” In the end, the striking cover graphic makes the meaning of the title abundantly clear, so we abandoned that idea. But the book really is about the full character of Portugal during its most oppressive period, with all the social classes represented, many of the social movements cropping up, the nature of work and the peasantry, the vast, unrelieved poverty, the place of women, the hypocrisies of the Church. We look inward and we look outward, people enter and leave the prison as inmates or as visitors, and what we see is a seamless composite tapestry of intimate pen-portraits of the author’s characters against a field of gritty social realism.

I am prejudiced, of course, but I do believe that The Six-Pointed Star, now available to a wider English-language readership, will join the select company of great books on this theme.

Atkins: Is it depressing?

Gordon: The main villain in the story is, of course, the fascist system itself, whose crimes are collectively far worse, in terms of how many people they harm than those of these unsavory prisoners. There is a kind of Noir sensibility about the book, which doesn’t flinch from exposing the noisy, metallic tedium of useless prison life, nor from telling some truly horrific, even voyeuristic tales of “true crime.” And yet, he’s a Communist writer. Almost by definition, he cannot come across as hopeless. Through it all, we see caring, friendship, sacrifice, compassion, intelligence, love, conscious political resistance, a passionate curiosity about the world, even a kind of saintliness, and all the other qualities that make humans human. Prison in and of itself does not cancel a person’s humanity. That may be in itself the single most important “message” the book is trying to communicate.

Atkins: Prison activists often say that the humanity of a system can be judged by how it treats its prisoners. Would Manuel Tiago agree with that?

Gordon: As a committed Communist, Cunhal appreciated that the successful development of each individual human being is important in equal measure with the success of the larger community and that they are interdependent. As a panoramic view of prison life, with many close-ups on any number of unique characters, Cunhal’s treatment inherently asks whether the full balance of an individual’s humanity can even be achieved under capitalist conditions, much less the fascist society he is describing. I think prisons in the Nordic lands may be the best they get, with an emphasis less on degrading punishment as such, and more on understanding and rehabilitation.

Atkins: At the end of Five Days, Five Nights you have a section called “Some Questions to Ponder and Discuss.” That’s a little unusual for a work of fiction, isn’t it? Unless it’s an edition intended for classroom use. Are you doing the same with Six-Pointed Star?

Gordon: Yes, we are, and yes, it’s unusual. But it’s also unusual for a publishing house like IP to release a whole series of fictional works—by anyone, much less in translation from a Portuguese writer. Its catalog is generally filled out by serious nonfiction works. Here’s my thinking on this. There are thousands of book clubs and study groups that might pick up one or more of the Manuel Tiago books, not to mention individual readers. This material is quite a bit off the beaten path for most readers, so I felt they might need some help sussing out the meaning and implications of these works. These discussion points make the act of reading a more collective process. I hope it doesn’t sound presumptuous of me, but as his first and only translator in English so far—speaking only of his fiction, of course—I don’t know how much longer I’ll be around to share whatever insight I’ve gained into these works. So I thought it best to do what I can now to aid this and the next generation of readers in approaching them. I’ve tried to formulate some leading questions that will encourage deeper appreciation of the unstated nuances of these stories, and people may not agree with one another in their answers. But at least they’ll have their opportunity to consider these points and express themselves.

Atkins: Anything more?

Gordon: Yes, one more thing I’d like to mention. The Portuguese are rightfully proud of their literary tradition and are eager to share it with the world. So they established a fund to give modest encouragement to publishers around the world that release translations of Portuguese writers. For this prison novel International Publishers earned the support of The General Directorate for Books, Archives and Libraries/DGLab and Camões, Instituto da Cooperação e da Língua. Of course, we’re very proud of that, and naturally, we give proper acknowledgment.

Order a copy of The Six-Pointed Star from International Publishers.