A new book by Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire, explores the history of police violence and Black resistance in U.S. cities during the 1960s and ’70s.

The first pages of Hinton’s eye-opening study describe the historic day in February 1960 when four Black students sat down at a whites-only lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. This was the origin of the famously nonviolent “sit-in” movement that brought demands for integration, voting rights, jobs, and education to 55 cities and 13 states.

Nine years later, students in Greensboro were still protesting, but not peacefully. Now the controlling dynamic was a “cycle of violence” between law officers and students, culminating in the killing of North Carolina A&T University sophomore Willie Grimes in May 1969.

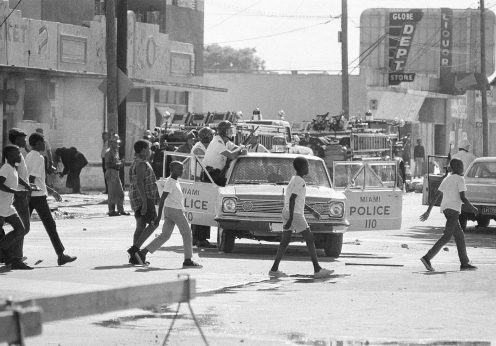

That Greensboro became a site of racial bloodshed was not unusual. As Hinton shows, “Between 1964 and 1972, the United States endured internal violence on a level not seen since the Civil War. Every major urban center in the country burned during those eight years.” Since then, the author asserts, Americans have been living in a nation and a national culture created in part by the extreme violence of this period.

A touchstone for Hinton’s analysis is the work of the Kerner Commission, appointed by Lyndon Johnson during the “long, hot summer” of 1967 to investigate the origins and motives of racial conflict in American cities.

The commission’s 426-page report, progressive for its time, found that the cause of urban “riots” was not Black lawlessness but white racism. It warned that American institutions were permeated by systemic racial injustice, and that the nation itself consisted of “two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

In accordance with the commission’s mandate, the Kerner Report identified a remedy. It called for full and immediate integration of Black citizens into “the mainstream of American life” and stated that this goal could only be achieved by massive investment of federal resources to equalize opportunity in minority communities.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, convinced that such “radical” conclusions were impossible to implement, ignored them. Instead, LBJ did what the USA frequently does: He doubled down on brute force. The “massive investment” that could have improved people’s lives was rerouted toward hiring thousands of police, equipping them with ever deadlier weaponry, and inserting them into African-American communities.

Hinton’s book does a historical deep dive into a great many Black protest actions. One that happened in my adopted hometown of Akron, Ohio, is a good example. Over four nights in August 1970, law officers brandished shotguns and used tear gas and night sticks to disperse street crowds in Black neighborhoods.

The mayor of Akron called a meeting of Black community leaders in order to find out, in his words, “what you people can do to help stop these kids from continuing their rampage.” The businessmen and agency representatives in attendance blandly replied there was little they could do.

But the tone shifted when four Black militants entered the room. They denounced the police and cited “200 years of repression from the white man” as the cause of the rebellion. When they made concrete demands for jobs, programs, and an end to harassment, the mayor and police chief refused to negotiate. That evening, the conflict in the streets resumed. When it was all over the local newspaper sided with the police without mentioning the grievances of the Black insurgents, who were called “hoodlums” and “far out radicals.”

In the Akron uprising, Hinton sees a lesson: “Perhaps if the Akron Police Department would have fully committed to de-escalation in the troubled community, this spate of renewed violence would have been prevented.”

Each well-researched chapter of America on Fire lays out similar encounters, both headline-making and little-known. Here is a partial list of book’s insights:

- President Johnson’s strategies repressed mass violence, but they ironically made further violence inevitable.

- The cause of the conflicts Hinton highlights was “unnecessary and aggressive police interventions in Black communities,” which accumulated into hostility and set off preemptive, violent reactions.

- The so-called urban riots of the 1960s and ’70s can only be understood as rebellions. They were not based on a wave of criminality; they were a sustained insurgency. They were not attacks on American institutions but appeals for inclusion within them.

- In this period there emerged a “cycle” of over-policing and rebellion, of police brutality and community violence that defined life in segregated low-income urban areas.

- In Black neighborhoods, aggressive policing became a fact of life. The message was that Black people should get used to police surveillance of their pickup basketball games, walks home from work, and family barbecues. Poverty and harassment gave residents good reason to rebel.

- Throughout the 20th century, whenever people of color disrupted the status quo, white people formed armed groups. In the East St. Louis massacre of 1917 and Tulsa massacre of 1921, white mobs, backed by law enforcement, destroyed the future of Black communities. On a smaller scale, this happened in dozens of cities in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

- The idea that “both sides” were responsible for the violence was based on the assumption that the status quo of second-class citizenship for Blacks was acceptable and should remain in place.

- White people could attack Black people and face no consequences; Black people were criminalized and punished for defending their communities. The white majority saw no reason to end the domination of political and economic institutions that systematically excluded African Americans from jobs, housing, and educational opportunities.

- U.S. policymakers had a choice between overwhelming brute force and positive meaningful action to remove racial inequities. They generally pursued the “punitive path,” and still do.

- The militancy of the Black Panthers and other groups was part of a broader movement to replace the white value system—capitalism—with a system based on cooperation and community. Since the capitalist state would not guarantee Black residents protection or rights, it was up to the people themselves.

Eventually the book’s analysis extends into racial conflicts in Miami in 1980, Los Angeles in 1992, Cincinnati in 2001, Ferguson in 2014 and yes, Minneapolis in 2020, all of which contribute to the presentation of striking truths that resonate today.

Elizabeth Hinton is a professor of law, history and African American Studies at Yale. Her book is valuable for its clear-eyed assessment of familiar social phenomena:

- Police violence causes community violence. The cycle of violence and rebellion can be broken, but not by the application of more violence. Patrolling low-income neighborhoods with outside forces does not promote public safety.

- Embracing mass incarceration as a policy response is counterproductive. Instead it functions merely as a crime promotion program.

- Full partnership and equal opportunity in all facets of society can’t happen while the white elite still holds racist attitudes that prevent it from truly sharing power.

- The “us against them” mentality of police culture must be replaced. The solution is not necessarily defunding the police but reimagining and restructuring their role as social service providers.

Hinton acknowledges that change is possible and that in 2021, some lawmakers are listening. But she predicts that the country “will continue to see the fires of rebellion.” Violence will not end, the author asserts, until the nation stops expecting police to manage conditions that are beyond their control.

America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s

by Elizabeth Hinton

Liveright Publishing, 2021, 396 pages

ISBN-10: 1631498908

ISBN-13: 978-1631498909