Prominent anti-apartheid activist Winnie Madikizela-Mandela died April 2 in Johannesburg, South Africa, after a long illness. She was 81.

Madikizela-Mandela may be best known in the U.S. as the wife of Nelson Mandela, to whom she was married from 1958 to 1996. Nelson Mandela, who died in 2013, was imprisoned throughout most of their marriage and Madikizela-Mandela’s own activism against white minority rule led to her being imprisoned for months at a time and placed under house arrest for years.

South African Nobel laureate and former archbishop Desmond Tutu said of Winnie: “She refused to be bowed by the imprisonment of her husband, the perpetual harassment of her family by security forces, detentions, bannings, and banishment. Her courageous defiance was deeply inspirational to me, and to generations of activists.”

Upon her death, the South African Communist Party (SACP) issued a statement:

“The contribution that Comrade Winnie made to the South African revolution, her sacrifices to the course, and on the other hand, the reactionary, repressive, and torturous responses she endured from the apartheid regime, can produce volumes of history, humanities, and social science books…. The SACP reiterates its perspective, in memory of Comrade Winnie, for the forging of a progressive women’s movement.”

Childhood and student days

Nomzamo Winifred Zanyiwe Madikizela was born in Bizana, in the Transkei [a territorial authority under apartheid’s Bantustan policy] on Sept. 26, 1936. Her father was a history teacher and her mother taught science.

In 1953, Winnie was admitted to the Jan Hofmeyr School of Social Work in Johannesburg, where she saw the full effects of apartheid on a daily basis.

Apartheid was a system of institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination that existed in South Africa between 1948 and 1994. The system was based on total white supremacy and the repression of the black majority (Africans, “coloureds,” and Asian South Africans) for the benefit of the minority of politically and economically dominant Afrikaners and other whites.

Winnie completed her degree in social work in 1955, finishing at the top of her class, and was offered a scholarship for further study in the U.S. She was also offered the position of medical social worker at the Baragwanath Hospital, making her the first Black member of staff to fill that post. Winnie decided to remain in South Africa. While working at the hospital, her interest in national politics continued to grow.

Life with Nelson Mandela

Winnie was 22 when she met Nelson; he was sixteen years her senior. He was already a famous anti-apartheid figure and one of the key defendants in the Treason Trial, which started in 1956. From the very beginning, their relationship was defined by a commitment to political change.

Despite government restrictions on the movements of Treason Trial defendants, Winnie and Nelson were married in Bizana on June 14, 1958. Their marriage was to prove both powerful and dangerous. Life married to one of apartheid’s most famous opponents was a difficult one, and the Mandela residence was a site of frequent police raids.

In October 1958, Winnie took part in a mass women’s action in Johannesburg to protest against the apartheid government’s infamous pass laws. The police arrested 1,000 women.

They decided not to apply for immediate bail, but to rather spend two weeks in prison as a further protest. Then pregnant, Winnie saw first hand the squalid conditions of South African prisons, and her commitment to the struggle only intensified.

It was this event that took Winnie out of Nelson’s shadow in eyes of the public, but also one that alerted national security to her own power as a voice of political dissent. Shortly afterwards, she lost her job at Baragwanath hospital, and then gave birth to their first daughter.

Nelson arrested, Winnie fights on

On March 30, 1961, nine days after the police murdered 69 people during an anti-pass demonstration at Sharpeville, Nelson Mandela was arrested in a police raid on the Mandela home, the beginning of his 27-year detention.

Realizing Winnie’s potential to carry on the cause, police slapped her with a banning order restricting her movements to Johannesburg, prohibiting her from entering any educational premises, and barring her from attending or addressing any gatherings where more than two people were present. Media outlets were no longer permitted to quote anything she said.

Police increased their harassment and intimidation, with regular raids occurring on her house. And agents of the state took advantage of Winnie’s imposed isolation to infiltrate her life and offer their support, while betraying her to apartheid officials.

At the end of May 1963, Nelson Mandela was transferred without warning to Robben Island, a place of isolation where many anti-apartheid activists were imprisoned. In June of that year, Winnie was permitted to visit her husband for the first time. She travelled 870 miles from Johannesburg to Cape Town before a six-mile journey over choppy seas to Robben Island. Once there the couple was allowed to meet for just 30 minutes, separated by wire mesh, no seats, and a security detail in easy listening distance. They were not permitted to speak to one another in Xhosa, only in English or Afrikaans.

Authorities even targeted their daughters, Zenani and Zindziswa. Winnie enrolled them in schools, only for the security police to insist that the schools have them expelled. This was in addition to the continued raids on her house, her banning order, and frequent last minute refusals to allow visiting her husband in jail.

Winnie described the harassment and trauma of the raids:

“That midnight knock when all about you is quiet. It means those blinding torches shone simultaneously through every window of your house before the door is kicked open. It means the exclusive right the security branch have to read each and every letter in the house. It means paging through each and every book on your shelves, lifting carpets, looking under beds, lifting sleeping children from mattresses, and looking under the sheets. It means tasting your sugar, your mealie meal, and every spice on your kitchen shelf. Unpacking all your clothing and going through each pocket. Ultimately it means your seizure at dawn, dragged away from little children screaming and clinging to your skirt, imploring the white man dragging Mummy away to leave her alone.”

In 1965, a new and more severe banning order was handed to Winnie barring her from going anywhere other than her neighborhood of Orlando West. She was hounded out of jobs. Due to her continued problems finding her daughters a school, Winnie eventually sent them to Swaziland where she was able to enroll them in school.

Winnie still continued to organize assistance for political prisoners. Then, on the night of May 12, 1969, she awoke to the familiar sounds of a police raid. After ransacking the property, they took her away in a police van, under the 1967 Terrorism Act, No. 83, which allowed the arrest without a warrant of anyone perceived to be endangering the maintenance of law and order, indefinite detention, and imprisonment in solitary confinement without access to a lawyer or a relative.

During a period of non-stop interrogation, Winnie was kept awake for five days and five nights. After every kind of coercion imaginable, the interrogation team brought a prisoner into the adjacent interview room and began torturing him. They made sure she could hear everything that was happening. Winnie’s interrogators told her that her silence was causing unnecessary pain to others fighting for the cause, and eventually, her will broken, she acquiesced. Not surprisingly, it has been speculated that like so many South Africans traumatized by the brutality of life under apartheid, Winnie may have long suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

On December 1, 1969, Winnie’s trial finally began. A well-respected human rights lawyer represented Winnie and co-defendants. After many complications, Winnie’s release was finally secured. She had spent a total of seventeen months in prison, with thirteen of those in solitary confinement, and was not convicted of anything in the end.

Winnie’s first banning order expired while she was in jail. Almost immediately upon being released, she was served with another, lasting five years. More stringent restrictions forbade her from leaving the house between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m. making it impossible to see her husband.

Winnie’s life outside of jail meant relentless police raids, with intrusions into her home sometimes happening up to four times a day. Her house was routinely burglarized, vandalized, and even bombed.

Youth movements and the Soweto uprising

By the mid 1970s, unrest amongst South African youth had become increasingly militant. Steve Biko had founded the Black Consciousness Movement in 1969. The formation of the all-black South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) followed soon after. Winnie found herself in a new role to as the symbolic mother to the burgeoning student movement. To the apartheid regime, she became a significant political figure in her own right, as opposed to merely being the determinedly courageous wife of Nelson Mandela.

In May 1976, just a few weeks before the famous student uprising in Soweto, Winnie helped to establish the Soweto Parents’ Association. Soweto, a township in the city of Johannesburg, was meant to exist only as a “dormitory town” for black Africans who worked in white peoples’ houses, factories, and gold mines. The uprising was a series of demonstrations and protests led by black schoolchildren that began on the morning of June 16, 1976.

Students from numerous Sowetan schools began to protest in the streets of Soweto in response to the forced introduction of the Afrikaans language as the medium of instruction in local schools. It is estimated that 20,000 students took part in the protests. They were met with fierce police brutality. The number of young protesters killed by police is usually given as 176, but estimates of up to 700 have been made.

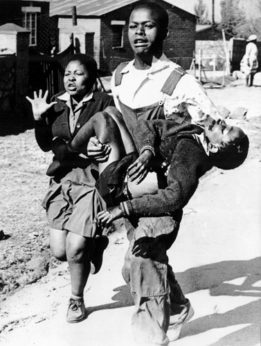

A photo by Sam Nzima became an icon of the Soweto uprising as it flashed worldwide: Hector Pieterson being carried by fellow student Mbuyisa Makhubo after being shot by South African police. His sister, Antoinette Sithole, runs beside them. Pieterson was rushed to a local clinic and declared dead on arrival. Winnie attended his funeral along with thousands of others.

In the weeks that followed, Winnie helped youth and parents who had been arrested, injured, or killed in the protests. The police attempted to pin responsibility for inciting the uprising on Winnie. Police held her in custody for five months, eventually releasing her in December 1976 without charge. In January 1977, she was served with a new five-year banning order.

Then, in the early hours of the morning on May 15, 1977, a police contingent arrived at Winnie’s doorstep to take her away. On instruction from the government, she was exiled to Brandfort, a small agricultural town around 25 miles southwest of Johannesburg.

Prior to her arrival, the Department of Bantu Affairs had informed locals that a dangerous female—a “terrorist”—would be moving there and that they should avoid contact with her at all costs. This backfired.

Instead of being demoralized by her isolation and the racism of local shop owners, Winnie continued flouting racist apartheid legislation and refusing to be cowed by unjust segregationist laws. Opinion polls taken during her first two years in Brandfort showed that she was seen to be the second most important political figure in the country (after Zulu chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi). While she was living out her banishment, she established a local gardening collective, a soup kitchen, a mobile health unit, a day care center, an organization for orphans and juvenile delinquents, and a sewing club.

Winnie’s banishment only came to an end in 1986. She was at last free to return home.

The ending of apartheid, the struggle continues

After years of anti-apartheid struggle and many fighters’ deaths, on February 2, 1990, President F.W. De Klerk unbanned the African National Congress (ANC). Just over a week later, on February 11, Nelson Mandela walked out of prison hand in hand with Winnie Madikizela-Mandela to a reception of hundreds of thousands of supporters. The couple was finally reunited after almost 30 years of separation, a separation that understandably took its toll on them and their marriage. They were divorced in 1996. As the mother of their two daughters, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and her ex-husband appeared to rebuild a friendship in the final years before his 2013 death.

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela remained a venerated figure in the ruling ANC, which has led South Africa since the end of apartheid. She continued to tell the party “exactly what is wrong and what is right at any time,” said senior ANC leader Gwede Mantashe.

Barbara Russum contributed to this article. Sources include South African History online (SAHO), Associated Press, and the South African Communist Party (SACP).

Comments