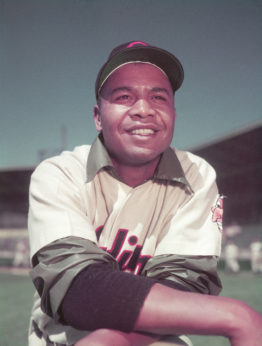

If you ask even the most casual baseball fan who the first African American to play in the major leagues was, virtually everyone would say “Jackie Robinson.” But if you ask them who the second African American was, you would most likely receive a blank stare. That’s not surprising in a society that values being #1, with all the rest just considered irrelevant. Which is a shame because that second African American was arguably a better overall player than the first.

Larry Doby debuted with the Cleveland Indians of the American League just 11 weeks after Jackie did with the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League. The racist abuse directed at Robinson has been well documented, but there are few recorded instances of such abuse of Doby, although undoubtedly there were (just look at the racist history of the Chief Wahoo logo and the recent debut of a commemorative #42 Chief Wahoo logo cap, in honor of Jackie Robinson—completely ignoring the racist abuse directed towards indigenous people). However, there were many times in the coming years when Doby faced the same poisonous racist attitudes as Robinson, particularly while playing spring training games in the South.

Doby didn’t have the immediate success that Robinson had in 1947, as he hit only .156 with no home runs and 2 RBIs in just 32 at bats and was used almost exclusively as a pinch hitter.

But 1948 was different: That season saw the emergence of Doby as one of the best hitters in the American League and the equal of Robinson. In his first full season,

Doby hit .301 and smacked 14 home runs and 66 RBIs while Robinson batted .296 with 12 home runs and 85 RBIs. As 2017 marked the 70th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s triumphant entrance into major league baseball, 2018 should be celebrated as the 70th anniversary of the arrival of Larry Doby, a Hall of Famer in his own right.

Doby was born in South Carolina, where his grandfather had been a slave. When Larry turned 14 he moved to Paterson, New Jersey, to live with his mother. In high school Doby was the only African American on the football and baseball teams and one of two on the basketball team. Those experiences helped to prepare him for the struggles to come.

Doby’s path to the major leagues was very different from Robinson’s. Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey signed Robinson to a professional baseball contract in August of 1945 and sent him to the Dodgers Triple-A team in Montreal for the 1946 season. Although he was the only black player in the International League, Robinson was well-received by the fans and his teammates in Montreal. However, when the Royals played games in the South, he heard the kind of racist insults he was to encounter the following year with the Dodgers. Rickey had intentionally let Robinson play one year in the minors with the expectation that Robinson would be on the Brooklyn team in 1947, and talked with him extensively about what to expect to hear during his first season and how to react to it.

Doby had no such time to prepare. On July 1, 1947, Cleveland owner Bill Veeck signed Doby while he was playing for the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League, and only days later Doby walked into the Indians clubhouse in Chicago. It was not the welcome he had hoped for. According to Doby, when he was introduced to the team, four players refused to shake his hand. When he took the field before the game to warm up, no one would play catch with him until second baseman Joe Gordon threw him a ball. Doby never forgot the gesture.

Black journalists and the Daily Worker

But Doby and Robinson might never have had a chance to play in the majors if it hadn’t been for a number of black journalists and several sportswriters for the Daily Worker, the Communist Party’s newspaper. As sports editor Lester Rodney recollected:

“We may have had a little something to do with that [Doby’s signing] too, because after Jackie came in, we kept mentioning other black players we thought had major league potential, and Doby was one of them. We saw him a lot because he played for the Newark Black Eagles right across the river from New York. So we began harping on Doby. When Veeck brought Doby directly up to Cleveland, he was consciously declaring that desegregation wouldn’t be confined to the National League. But Doby was overwhelmed. He had a terrible first year with Cleveland. They easily could have dropped him. But Veeck didn’t want to give up. He asked Lou Boudreau, Cleveland’s playing manager, and Lou said, ‘This guy’s gonna be a good hitter but he’s pressing. Let’s move him (from second base) to the outfield. He’s young and fast,’ so that’s what they did, and the next year—this was 1948—he was a key guy in pushing the Indians to the pennant and World Series championship, the last Cleveland won.”

Read the Daily Worker’s original 1947 Opening Day coverage from Lester Rodney.

Doby appeared in his first game as a pinch hitter and struck out. A greater disappointment awaited him after the game. He didn’t stay at the Del Prado Hotel with his teammates, but at the DuSable Hotel located in the largely black South Side of Chicago. This wouldn’t be the last time that he had different accommodations—something he would suffer more often than not for the rest of his major league career.

When Doby made his home debut in Cleveland a few days later, there were no protests by fans, and there is no record of any taunting by the Philadelphia players. One week later, two more black players, Henry Thompson and Willard Brown of the Kansas City Monarchs, were given contracts by the St. Louis Browns, but they were both released 30 days later. It looked like the American League clubs might integrate more quickly than National League teams. When the Indians played in Washington at the end of July, a group passed out flyers with the title “Why Wait Senators?” that implored fans to contact owner Clark Griffith and ask him to sign black players as the Indians and Browns had done. It didn’t do any good: Griffith wouldn’t hire a black player until 1954, seven years later.

Doby’s struggles at the plate prompted several scouts to suggest that he would have been better off in the minors for his first year as Jackie Robinson had done, instead of going directly to the major leagues. It’s possible that owner Bill Veeck, being aware that Cleveland’s two farm clubs were located in Oklahoma City and Baltimore, two cities with large Southern white populations, believed it would have been more difficult for Doby to cope with those crowds than the ones in major league cities, none of them located in the South.

Unfortunately, many of the Indians’ spring training games were played in Southern and Southwestern states, where Doby was treated like any other black person. In Tucson, where Cleveland had its training facility, Doby was refused a room at the Santa Rita Hotel where the rest of the players stayed. Instead, he ended up staying with a local black family in March of 1947 and every spring training until 1954.

His experiences as a player were even worse. At the Lubbock, Texas, ballpark, he was denied entry because he wasn’t wearing his Indians uniform. It was only when the team’s traveling secretary showed up that he was finally let in. When the team was scheduled to play in Texarkana, Doby put on his uniform before going to the ballpark. Unable to get a taxi because of Jim Crow, he walked to the stadium but was again refused entry, even though he had his uniform on. When manager Lou Boudreau showed up, Larry was finally let in. Things weren’t any better inside the ballpark: Doby had to be removed from the game in the fifth inning when bottles were thrown at him.

A few days later in Houston, racist taunts were hurled at him when he came to bat against Larry Jansen, one of the best pitchers in the National League. Doby responded with a 500-foot home run over the centerfield fence. Although some of those same fans applauded him as he rounded the bases, he was still seething, recalling that “I resented their cheers.”

Larry Doby, Satchel Paige, and Steve Gromek

Doby would not be the only black ballplayer with the Indians during his break-out season. Ageless Satchel Paige, considered by many as the greatest pitcher of all time, was signed by Veeck on July 7, one week after signing Doby. Doby and Paige became roommates, but it wasn’t a comfortable relationship. The 42-year-old Paige loved catfish and he would fry them up in their hotel room, which irritated Doby to no end as he hated catfish. “They live in the mud and eat anything,” he said.

But when Doby, incensed by a racist heckler in St. Louis, attempted to get to the fan and use his bat to stop the abuse, Satchel was one of the players to keep Doby away from him. Paige did much to help Cleveland to the pennant in 1948, appearing in 21 games, throwing two shutouts, and finishing the season with a 6-1 record and an ERA of 2.48.

Although Doby started poorly in 1948, he began to hit consistently in June, and by the end of the season he had established himself as the Indians’ centerfielder of the future. Cleveland, New York and Boston had been fighting each other all summer for the pennant, and down the stretch of the last 20 games Doby hit .396 with 3 home runs and 10 RBIs. Cleveland won the one-game playoff against the Red Sox, and the Indians won their first pennant since 1920.

In game four of the 1948 World Series, Doby homered to help pitcher Steve Gromek to the 2-1 win. A photo of the two of them hugging each other was published in newspapers throughout the country—probably the first time that readers had seen black and white athletes celebrating together. Doby recalled that “the picture was more rewarding and happy for me than actually hitting the home run. It was such a scuffle for me before that picture. The picture finally showed a moment of a man showing his feelings for me. I think enlightenment can (result) from such a picture.”

Cleveland went on to win the Series in six games over the Boston Braves, and when Doby and his wife Helyn returned to Paterson, they were greeted with a banner over City Hall that read “Welcome Home Larry Doby. Paterson is proud of you.” A crowd of 3,000 people attended a ceremony to honor Doby. He was the toast of the town—but not to everyone. When Larry and Helyn tried to buy a house in an upscale neighborhood in Paterson, all of a sudden there were no houses for sale or they had been sold just before the Dobys arrived. Doby had endured enough abuse and wasn’t going to put up with this. With the help of the mayor, Larry and Helyn found a house in an attractive middle-class neighborhood.

Larry Doby played a total of 13 seasons: Ten of them with Cleveland, two with the Chicago White Sox, and there was one more year when he played part of the season with the Detroit Tigers and part with the White Sox. He ended up with a .283 lifetime batting average with 253 home runs and 970 RBIs. Doby was voted by fans to the American League All-Star team seven times, playing in seven All-Star games in seven of his ten seasons with Cleveland.

He had 5-100 RBI and 8-20 home run seasons (five seasons in which he drove in 100 or more runs, and in eight seasons he hit 20 or more home runs). Doby played 166 straight games without an error in centerfield. He was the first black player to lead either major league in home runs. In 1954 he led the American League in home runs and RBIs and finished second in the voting for Most Valuable Player.

#2 once again

In 1978, Doby took over as manager of the White Sox in mid-season and won 37 games while losing 50. Unfortunately, Bill Veeck, former owner of the Indians and now his boss of the White Sox, thought the team should have won more games, and Doby was let go at the end of the season. In an odd coincidence, Larry Doby was second again: Frank Robinson became the first black manager in the major leagues when he was hired by Cleveland—the team Doby had hoped to manage someday—on October 3, 1974.

Larry Doby was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on March 3, 1978. On April 3, 2017, Republican Rep. Jim Renacci of Ohio’s 16th Congressional District introduced a bill, along with Democrats and other Republicans, to “award a Congressional Gold Medal in honor of Lawrence Eugene ‘Larry’ Doby in recognition of his achievements and contributions to American major league athletics, civil rights, and the Armed Forces during World War II.” One year later, it hadn’t come up for a vote, even though it was sponsored by a Republican in a Republican-controlled Congress.

When asked how he was able to deal with racial prejudice throughout his career, particularly in the first few years, Doby said, “I had to take it. But I fought back by hitting the ball as far as I could. That was my answer.” He died in 2003 at the age of 79.

In his memoirs, Bill Veeck echoed what a lot of players and sportswriters believed when he said, “If Larry had come just a little later, when things were just a little better, he might very well have become one of the greatest players of all time.”

Comments