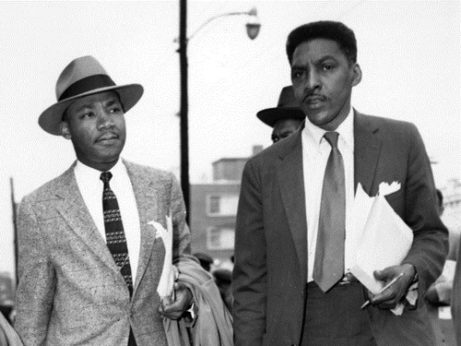

As America observes the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, there is one name you may not hear: Bayard Rustin. A close confidant and mentor of King, Rustin (1912-1987) was a key leader of the civil rights movement and chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He proved to be a transformative figure in the fight for racial justice, even introducing King to the Gandhian principles of nonviolence that would come to define the struggle. He also happened to be gay.

Rustin understood that we are all connected. His commitment to solidarity and passion for organizing made him a natural fit for the labor movement. He launched the AFL-CIO’s A. Philip Randolph Institute to extend the fight for economic justice to people of color. He knew that achieving a just society required securing jobs and freedom for all Americans. That vision for an inclusive, empowered coalition resonates just as powerfully decades later.

“I think the most important thing I have to say is…try to build coalitions of people for the elimination of all injustice,” Rustin said in the final years of his life, reflecting on the continuing fight for social change.

“Because if we want to do away with the injustice to gays, it will not be done because we get rid of the injustice to gays. It will be done because we are forwarding the effort for the elimination of injustice to all. And we will win the rights for gays or blacks or Hispanics or women within the context of whether we are fighting for all.”

Today the forces of division and greed are relentlessly trying to draw lines of separation based on race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Rural against urban. Black against white. Gay against straight. Immigrant against native-born. And economic security against social justice. Rustin knew these were false choices. That’s why he deliberately put himself at the intersection of every major movement for broad, progressive change.

As a young man in the ’30s and ’40s, Rustin never hid his sexuality. He was proud and self-assured, and that was deemed a liability by some of his fellow civil rights leaders. Rustin was forced to operate behind the scenes. He was rarely allowed to serve as a spokesman, and even his leadership of the 1963 march was downplayed publicly. The movement for racial justice was hurt by that concession to homophobia.

At the same time, the labor movement struggled with its own institutional racism. Black leaders were few and far between. Contracts were not always equal. Some white members resisted integration. It’s a history we are still working to overcome today.

If Rustin taught us anything, it’s the importance of being our fully authentic selves and standing shoulder to shoulder against those who seek to divide us. No exceptions. No apologies. To win an economy and a society that are truly fair and just, no one can be left behind and no one should be asked to hide who they are.

Rustin was a bridge builder. At the A. Philip Randolph Institute, he forged an interracial coalition dedicated to promoting equality and freedom for all. By doing so, he helped pave the way for today’s generation of openly LGBTQ union leaders, including Randi Weingarten of the American Federation of Teachers and Stuart Appelbaum of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, a part of the United Food and Commercial Workers, to take their place on center stage.

Rustin also embodied the profound importance of the labor movement to the LGBTQ community. Today, in half of all states, the only thing protecting workers from being fired because of who they are is a union contract. And LGBTQ union members increasingly have a voice on same-sex spousal benefits and transgender health care. At Pride at Work, we are continuing to push for progress, including passage of long-overdue federal employment nondiscrimination legislation.

Bayard Rustin said to be afraid is to behave as if the truth is not true. We are not afraid. And our truth is clear. Working people need each other. We stand on the shoulders of heroes who dreamed and marched and fought and organized. King envisioned a united progressive coalition building a more just and equitable society. Rustin helped bring that work to life every single day. Let’s remember them both and let’s honor their memory by doing our part to finish the job.

This article also appeared in The Advocate, “the world’s leading LGBTQ+ news source,” reposted by permission of the authors.

Shellea Allen is a co-president of Pride at Work.

This article originally ran in People’s World on April 5, 2018.

On February 5, 2020, California Gov. Gavin Newsom pardoned Rustin in line with his program of pardoning those prosecuted in the state by virtue of discriminatory laws.

In 1953 Rustin had been arrested in Pasadena on a “morals charge” after being found with another man and having consensual sex in a parked car. Rustin spent about eight weeks in jail for that “crime.”

“In California and across the country,” Gov. Newsom said in a written statement, “many laws have been used as legal tools of oppression, and to stigmatize and punish LGBTQ people and communities and warn others what harm could wait them for living authentically.” At the same time, Newsom encouraged others seeking exoneration on similar charges to make their cases known. In the 1970s California reversed the law making consensual same-gender sex a crime. It is time, Newsom added, to provide relief from the “abuses of the past.”

Eric A. Gordon contributed the above information to the article.

Comments