In the Far East of Russia, near the city of Khabarovsk, a 14,000 square-mile area slightly larger than the state of Maryland borders on China with an estimated population of 170,000. The name of its capital, Birobidzhan, with 75,000 inhabitants, is often used to refer to the whole district, which is officially called the Jewish Autonomous Region (JAR).

The Trans-Siberian railroad passes across the region, connecting Europe with Russia’s Pacific Asian coast by the shortest route. The Amur River on the JAR’s southern border provides a waterway out to the Pacific Ocean.

Birobidzhan, seven time zones east of Moscow, is a curious anomaly of history.

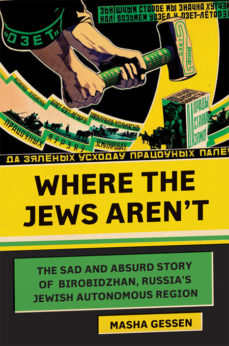

Jewish-Russian-American lesbian writer Masha Gessen’s new book Where the Jews Aren’t: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Region is more of an interpretation than a history, and is almost uniformly depressing in what it recounts. About the only “fun fact” one can cite is its post-Soviet era flag, a white rectangle crossed horizontally by seven narrow stripes symbolizing a rainbow. Anyone would be forgiven if they thought it was the flag of the LGBTQ Autonomous Republic.

Holding and governing the wide, sparsely populated Siberian expanse has been a challenge ever since the Czars claimed national sovereignty over all that land clear out to the Pacific. In the 19th century they sent Cossacks out to establish villages there and start taming the wilderness as a protection from potential future incursion from the far more populous China. Russia – under any regime – has always been sensitive about its borders.

Gessen’s principal contribution is to situate the Birobidzhan story in historical and theoretical context. Only after the rise of the national movements in the 19th century was it even possible for Jews to imagine a “national” homeland. To do so was to re-imagine Jews as more than a religious subset of society, but in ethnic terms as a “people” like any other. The secular Jewish historian Simon Dubnow formulated the idea of Jewish autonomism, the theory of cultural, ethnic, religious, linguistic, and in some ways legal independence of a group living within the outlines of a larger nation-state. A hundred years ago, achieving such a recognized status in Europe seemed far more achievable than the quixotic, visionary Zionist project of re-establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine, which few Jews embraced.

After the Russian Revolution, the new Soviet Union had a plethora of “national” questions to settle. Certain constituent republics, such as Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, etc., were logical entities, as they held a substantially homogeneous population with its own language and territory – and not coincidentally, all of them either on a foreign border or a Soviet coast.

And then there were dozens of peoples with their own languages and cultures living on land they had historically inhabited, that for various reasons were not numerous or advanced enough, or suitably situated geographically to merit “republic” status but could be considered in the light of “autonomist” theory. Marxist theoreticians spent whole careers fine-tuning the definitions of nationality in order to organize them into the USSR. Their culture was encouraged and promoted as long as it was “national in form, socialist in content.”

In 1934 the JAR was formally established as the answer to the Jewish people’s centuries-long yearning for a homeland of their own, with Yiddish, the Germanic language spoken not universally but very widely by European Jews, as one of its official languages. Hebrew, the language of religion, and of the growing Zionist settlement in Palestine, was repressed.

A few Soviet Jews were excited by the JAR, and some from capitalist countries as well, but most preferred the intellectual and social stimulation in the big cities of European Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Early settlements in the JAR were crude and pathetic.

But the fate of the Jews was inevitably tied to the fate of the USSR, and almost as soon as the “autonomous” region came into view, the political purges of the mid-1930s started. Loyal comrades who had sacrificed everything for their ideals were suddenly arrested, tried, and liquidated. The top leadership of the JAR similarly suffered such decapitation.

For a while, during Great Patriotic War (as World War II is known to the Russians), the Central Asian republics of the USSR and also the JAR provided refuge from the Nazi Holocaust. But almost as soon as the war was over, Stalin once again went on a rampage, against perceived spies, rootless cosmopolitans, foreign accomplices, traitors to the country and the party, and nationalists. Gessen lays out this sorry history as it affected the Jews, but in fairness she might also have brought out that the crackdown against “nationalism” affected all of the ethnicities in the Soviet Union. A policy of Russification came to be applied with a broad brush across the Soviet lands.

Gessen is understandably concerned for the fate of her fellow writers, and uses the case of David Bergelson over many chapters of her short book (170 pages) to trace the Birobidzhan story. It’s valuable to hear about this deeply conflicted man who constantly juggled all of his loyalties- family, linguistic, literary, religious, political, and national. He was among those Jewish poets, writers and community leaders prominent in the wartime Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, whom Stalin had executed on August 12, 1952. (They were posthumously acquitted in 1955, after Stalin’s death.) Much of her book is really more about the general Soviet Jewish experience – which she lived personally – than Birobidzhan itself.

She also gives us shorter pen portraits of other writers and denizens of Birobidzhan whose devotion to Yiddish compels admiration, but all too little and too late. Her sources, however, do not seem to include books in Yiddish.

Today almost no one speaks Yiddish in Birobidzhan, although since the fall of the Soviet Union there is something of a religious and cultural revival. No more than ten percent of the population there even has any Jewish roots, much less considers itself Jewish. Some tourists visit this still named “Jewish Autonomous Region” out of a sense of curiosity about what might have been – a modern, secular, socialist, self-governing, mostly agrarian Jewish Arcadia – but it remains, as it always was, a dreary backwater of Jewish life.

In one way, at least, the dream of a thriving community way out in Eastern Siberia did produce a positive result, although not particularly Jewish. It did help to establish and settle Russia’s borderland area and insure the country’s territorial integrity at least for the foreseeable future, and that was in large part the point of it all from the beginning.

Masha Gessen

Where the Jews Aren’t: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Region

New York: Shocken/Nextbook, 2016

170 pp., with index and bibliography