Bisbee, Arizona, is a haunted city. It’s a Mexican border town and just 35 miles from Tombstone, where staged gunfights at the O.K. Corral are a daily faked tourist attraction.

At one time the richest city in Arizona, it’s haunted by the memory of the Phelps-Dodge copper mines that were its reason for being for a century beginning in the 1870s. Now they are closed. Today it’s a fairly liberal-minded place, populated by long-time residents who have deep roots there, and by a new demographic of visitors and tourists who have fallen in love with its old-timey Western romance, its scenic desert beauty, and its openness to artists and freethinkers. A substantial percentage of the population, then and now, is Mexican American.

And Bisbee is truly haunted by the tragic events of July 12, 1917. The town’s Copper Queen Mine was in its heyday producing copper for war munitions. Most of the workers were Mexican, Mexican-American, or immigrants from Europe’s Slavic countries. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) had organized them to declare a strike when their demands for better pay, safer working conditions, and for an end to racial and ethnic discrimination were summarily rejected. Some of its more politically advanced members may also have wanted to put a crimp in the war machine.

Cochise County Sheriff Wheeler formed a posse, deputizing and arming hundreds of men to “save the women and children” from the socialist, communist “mob” whose radical demands threatened the company’s wartime profits. Deputies raided homes, rounding up an estimated 1200 Wobblies and anyone else they perceived as sympathetic to the workers. Guns drawn, they surrounded a march of strikers, forcing them into a nearby ballpark. The authorities gave them one last chance to return to work, but no one budged. Instead, they sang “Solidarity Forever,” with some verses in Spanish.

Many “respectable” townspeople believed a so-called “law of necessity” applied, which overruled any established legal notions of due process. The workers were nothing more than “rattlesnakes” with whom there was no compromising. They were vermin to be eradicated, told they would be killed if they ever returned to Bisbee. Friends and neighbors assisted the deputies in the roundup. Some Wobblies who resisted were shot in their own homes.

The striking workers were placed into boxcars and shipped eastward. They were dropped off in the desolate, burning New Mexico desert without food or water and left to their fates.

Funny thing, though: All the deputies were Anglo men, and all the deportees were either Mexican-American or immigrants. The action had more the aspect of an ethnic cleansing than the settlement of a labor dispute. Who defines who is American? It’s one of the longest-running unanswered questions in U.S. history.

As the centennial of these events approached, how did the people of Bisbee face this history? How would they mark the occasion? With smug satisfaction that their granddaddies did what was right, if not what was legal; or with revulsion at the abuse of men who sought only to improve their lot in life? Some families were divided. But again, all the old racial splits in town came to the fore.

A citizens’ commission came together and decided they would stage a community-wide re-enactment of the day. Documentary filmmaker Robert Greene, a professor of film at the University of Missouri, thought this might be a valuable opportunity to examine how a town assesses its violent past. In some ways, the project of making the film, choosing and interviewing subjects, recruiting residents to become the sheriff, the mayor, the Mexican IWW agitator, the Mexican-American teenager torn between his protective mother and the workers’ clear rationale for striking, became a giant Truth and Reconciliation session for the town.

In the Ray family, a deputized grandfather arrested his own brother who was allied with the strikers, and sent him off on the train to an uncertain destiny, left as food for birds, as a ballad of the time relates. Susan Ray’s two sons, Mel and Steve, play their grandfather and great-uncle.

A self-described actor, James West, plays the part of the mine manager, John C. Greenway. Interestingly enough, while “between jobs” that rarely materialized, West had worked for the federal government doing security on planes deporting people back to their home countries.

Conceived in the fall of 2016, when Greene paid a visit to Bisbee (his mother-in-law had a sweet little vacation cottage in town), the project spun off into another dimension when, against expectation, the man who came in second in the popular vote became president. By the time of the July 12, 2017, re-enactment, U.S. policy toward immigrants had turned into a virtual replay of the hysteria of a century before. Now the word “deportation” came alive with new meanings that no one in Bisbee would ever forget again. “The subtext is text,” Greene said at a post-screening talkback Sept. 25 at the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts hosted by Professor Michael Renov. “By December 2016, people knew this film was going to mean something else.”

“The movie could work if you care about the people,” Greene added. Although the film includes a few scripted scenes—such as the wrenching mother-son conversation played by Mary Ellen Dunlap, the first Hispanic—and the first woman—elected (as a Republican) as a clerk of the Superior Court, and a local teenager Fernando Serrano, who plays what might be called the moral center of the film; or the panel of owners declining to negotiate (which amusingly includes “God, Country and the Copper Queen Mine,” an original bosses’ song, of which there are few in the folk literature)—much of the rest of the film evolved organically.

Townspeople chose the roles they wanted to play, and thought of words their characters would say. It was critical for the filmmaker, who also wrote and edited, not to reach consensus on the meaning of the events a century ago. For many it is still part of their personal and family identity to defend the rightness of their forebears’ actions one way or the other. “I’m definitely not interested in objectivity,” Greene said. “It’s not balanced, it’s human.” On the other hand, he expanded in response to a questioner, “You can’t see cattle cars and not think of the Holocaust.”

In a twist of ultimate irony, most of the deportees did not die out in the boiling July New Mexico desert. The IWW was militantly against World War I, yet they saved their lives either by enlisting or being drafted into the army. Perhaps, as one of the Wobblies speculates, the owners refused to negotiate because they had simply gotten out of the workers what they needed.

No one was ever indicted for carrying out the illegal vigilante deportation. It almost got lost to history.

As a documentary, the film takes some risks. It’s shaped into six “chapters,” which Greene explained saying that as he reviewed his footage, the material suggested several starting points. It reworks some old Wobbly songs from the famous Little Red Songbook, as if surrealistically streaming through the characters’ minds, especially that of the teenage Fernando (the musical direction is by Keegan DeWitt). It establishes place by seconds-long shots of interviewees as they silently prepare to speak.

We are never to forget that the film is essentially about people today relating out of their own experience to the sad episode of a century ago. We actually go into some of the 2000 miles of tunnels in the mine, so the cinematographers (lead credit to Jarred Alterman) get to play with many types of chiaroscuro effects. Footage of the mine pits paints the screen in abstract geological art. The film title obviously compresses two dates a century apart into one abbreviation.

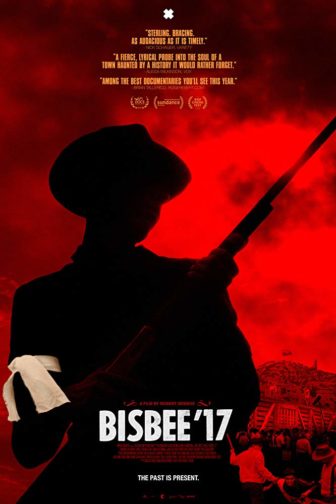

Bisbee ’17 is remarkable, passionate and important filmmaking. Don’t let this one slip away. It opens at the Laemmle theatres in Santa Monica and Pasadena, Calif., on Sept. 28. Check local listings for future nationwide release.

A trailer for the film can be viewed here.