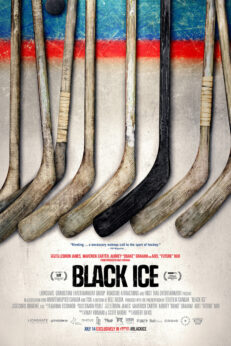

The new documentary Black Ice is a hard-hitting deep dive into the world of hockey and the history of Canada when it comes to race, racism, and Black Canadians. There are facts and revelations that challenge the narrative around race in the sport—and also pushback against the widespread image of a country that mainstream popular culture likes to consider the “gentler” part of North America in comparison to the United States. The film will no doubt ruffle some feathers (on both sides of the border), challenge some long-held beliefs, and ultimately (hopefully) bring forth a deeper conversation regarding the history of hockey and the role Black people have played in a variety of Western cultures.

Directed by filmmaker Hubert Davis (Hardwood), Black Ice displays the challenges, triumphs, and unique experiences faced by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) hockey players past and present. The film mixes firsthand accounts by a variety of professional players with a historical exploration into the roots of the game, dating as far back as the mid-1800s. Director Davis also tackles racist patterns that have spanned generations and continue to influence hockey and the country of Canada as a whole.

Directed by filmmaker Hubert Davis (Hardwood), Black Ice displays the challenges, triumphs, and unique experiences faced by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) hockey players past and present. The film mixes firsthand accounts by a variety of professional players with a historical exploration into the roots of the game, dating as far back as the mid-1800s. Director Davis also tackles racist patterns that have spanned generations and continue to influence hockey and the country of Canada as a whole.

There’s something in the documentary for both sports and history lovers. For starters, if you thought hockey was a predominantly white sport with hardly any players of color, then this film serves as a nice introduction to the fact that this very prevalent view is a false one—and has been since the inception of the sport. Viewers will hear from present Black hockey stars like P.K. Subban and Wayne Simmonds and see a harrowing interview with former professional hockey player Akim Aliu, who dared to speak out against the racist abuse he suffered at the hands of a former coach in a world where players of color are encouraged to simply keep their heads down and play.

Black Ice explores the story of the Colored Hockey League (CHL), which was an all-Black ice hockey league founded in Nova Scotia in 1895. The league featured teams from across Canada’s Maritime Provinces (a region of Eastern Canada consisting of the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island), and operated for several decades, lasting until 1930.

The teams that were part of this league had names such as “Jubilee” and “Moss Backs,” which on the surface seem simple enough, but actually connect to coded language in reference to the Underground Railroad (a network of secret routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early 19th century to help enslaved African Americans escape into free states), and the emancipation of enslaved Black people in the Americas.

The time period of the CHL’s existence also upsets another narrative—that concerning exactly what kind of communities have made up the Black presence in Canada. While there is a significant population of relatively recently immigrated Black Canadians of Caribbean and African origins, the history of Black people in Canada goes much further back. Black Ice touches upon the fact that Canada was often the last stop on the Underground Railroad and that many Black people set up their homes in Canada and have contributed to the culture.

The film connects the racism faced by Black hockey players to the anti-Black experiences Black Canadians have faced for some time. One activist in the doc expresses how often Canadians pride themselves on being “better” at race and inclusion than the U.S., and that they hold onto the notion that “America is where the real racism is.” Yet, history tells a different story.

Black Ice doesn’t just want to talk about hockey, it aims to make the connection of how hockey is a reflection of a larger society afflicted by systemic racism that stands in the way of true progress. The film goes to great lengths to have local activists and advocates really break down what systemic racism is and how it isn’t just a racist player or manager here or there, but rather an environment that emboldens racists to be racist without any repercussions.

This is also not just an issue relevant to the experience of men. Black Ice also takes time to focus on Black women hockey players past and present. A highlight of the film is Saroya Tinker’s story about being a Black woman professionally playing hockey today and the challenges she has faced. Blake Bolden, the first African-American player to compete in the National Women’s Hockey League, also tells her story of discrimination despite her love for the sport.

Socio-economic issues are taken on, such as how working-class young people—mainly of color—are being priced out of pursuing the sport completely because they often don’t get assistance regarding expensive equipment needed to train. Hockey’s not a cheap sport, and kids’ hockey charities like the one run by Canadian donut chain Tim Horton’s simply aren’t enough. For a sport so closely identified with Canada, the film questions why it is seemingly icing out (pun intended) potentially future stars of the game based on race and class.

There is a lot to take in when watching Black Ice, but director Davis does a fine job of putting forth the themes in a digestible way. Despite the film being hard-hitting with facts and information, the aesthetic of the doc is gentle and cozy. This may not appeal to some who need a constant barrage of vibrant graphics and music to keep their attention when watching a film. Instead, the movie seemingly invites viewers to get comfortable as they take a journey through over 100 years of hockey history and race relations in Canada. Davis is correctly confident in the fact that the topics, interviews, and revelations are compelling enough without all the bells and whistles.

Black Ice will no doubt garner attention due to superstar athlete Lebron James and music star Aubrey “Drake” Graham being executive producers on the project, but it is attention well deserved. As an interviewee in the doc expresses, “We [Black people] are integral to everything this country [Canada] thinks it is.” This sentiment is felt throughout the film in a powerful way.

Viewers may never look at hockey—or Canada—the same way again.

Black Ice will play exclusively in AMC Theaters nationwide on July 14, 2023.