LOS ANGELES — The Hollywood Red Scare, lasting from 1947 to about 1960, was not the first in the United States. The first goes back to the Chicago Haymarket Affair of 1886 in the midst of a mass movement calling for the eight-hour day. Anarchists were hanged for that. A generation later, the government targeted the revolutionary syndicalist union, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or “Wobblies”), as well as the radical Socialists led by Eugene V. Debs, erasing their free speech rights and putting integrated labor and immigrant communities under sanction. Once again, after the Russian Revolution, capitalist politicians, fearing that American Communists might instigate a movement to overthrow the government, resorted to mass deportations. The anti-radicalism, racism, and nativism of those eras find their echoes today in the anti-woke MAGA hysteria that extends far beyond the persona of our immediate past president.

In an authoritative, comprehensive exhibition currently on view at the Skirball Cultural Center, visitors can explore the history and impact of the Hollywood Red Scare and its contemporary implications. What the red scare of the Forties has in common with its predecessors is the abandonment of civil liberties, First Amendment protections for speech, association and assembly, in the rush for exemplary “patriotic” punishment, intimidation, and imprisonment.

The show was created by and is on loan from the Jewish Museum Milwaukee, but augmented by images and artifacts specifically relating to Los Angeles.

In October 1947, in the wake of the Allied victory in World War II and in the ramp-up of panic over America’s new enemy, its erstwhile ally the Soviet Union, the House Un-American Activities Committee called on Hollywood figures to testify about allegations of Communist propaganda in American films. No convincing evidence was ever found of it, but in the frenzy of the times, the film industry became the first mass employer to adopt a blacklist against employees whose political beliefs ran counter to government- and corporate-generated propaganda against socialism.

The late Forties were a time of labor upsurge, with many pent-up demands coming forward that had been downplayed for almost a decade in the interest of wartime unity. The march of socialism around the world—the Soviets recovering from war, Eastern Europe, China, even the popularity of Communist parties in Western Europe—threatened U.S. global hegemony. What if the U.S. labor movement turned radical again?

As the exhibition turns its spotlight on congressional proceedings, investigations, and motives, as well as the various ways creatives and executives responded, it demonstrates not so much “how the politics of Hollywood can shape the entire country,” as its didactics state, but how the politics of the country shaped not only Hollywood but the entire cultural, intellectual, economic, social and environmental character of the country.

The attack against Hollywood—to yank it into conformity with post-war U.S. exceptionalism—was cut of the same cloth as the attack on Communists in the labor movement. Although the jailed Hollywood Ten are much talked about and written about, it was thousands of other workers, in the motion picture industry and more broadly throughout the labor movement, who also, away from the bright lights, suffered the stings of blacklisting, firing, and loss of employment.

Panels and display cases treat such topics as the larger political witch-hunt against the left would be most dramatic, most effective, if the nation could be shown that even some of their most admired actors, writers, and directors, could be shown to be treacherous snakes answering to Moscow’s call.

The broader labor aspect of the story largely escapes the creators of Blacklist, but not utterly. On display is an “Advance CIO Bulletin” dated Sept. 26, 1945, in which a loud-mouthed Rep. John Rankin of Mississippi was overheard in the House restaurant outlining his scheme. His bluster was taken down and summarized:

- The Committee will go out to Hollywood for a quick job on alleged red influences in the movie industry—especially among the screen [writers]. Incidentally, garner lots of publicity in the process.

- Bring a few real life Communists to Washington for investigation here.

- [And] here’s the payoff—tie in the whole thing with the unions, especially those of the CIO. They’re to be the real targets.

Indeed, despite the presence, several times, of union organizing as a theme in the recent film Oppenheimer—of academics, students, technicians, lab workers, etc.—the connection between the threat to the establishment of workers organizing and the threat of Soviet-sponsored spies has been little commented upon.

It’s not to be forgotten that many of the congressmen who interrogated Hollywood creatives had opposed FDR’s New Deal not even a decade before, and were in no rush for the U.S. to enter the war against Nazi Germany.

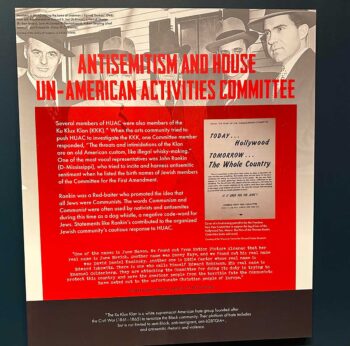

Why is it Jewish museums—in Milwaukee and now in L.A.—are so interested in the Blacklist? That’s not hard to answer: Six of the Hollywood Ten—John Howard Lawson, Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, and Samuel Ornitz—were Jews. And many of the studio founders and officers, who feared for the success of their empires if they dared stand up to the censors, were also Jewish. Part of the human interest is precisely to examine the drama of those caught in the crosshairs—both those who suffered under and those who enforced the blacklist.

Though not particularly focused on in the exhibition, it was also the era of the Rosenbergs’ ordeal. In a post-war era when colleges still limited admission of Jews, when housing covenants still forbade selling property to Jews, when social clubs excluded Jews, the national ethos connected Jews with communism, spying, cosmopolitanism, disloyalty.

Though not particularly focused on in the exhibition, it was also the era of the Rosenbergs’ ordeal. In a post-war era when colleges still limited admission of Jews, when housing covenants still forbade selling property to Jews, when social clubs excluded Jews, the national ethos connected Jews with communism, spying, cosmopolitanism, disloyalty.

It was not hard for Jews to see the HUAC hearings as a new iteration of the Spanish Inquisition’s show trials, its autos da fé. As the exhibition’s informative panels tell us, “Witnesses could not cross-examine those who accused them as they would in a trial, despite efforts by attorneys for both ‘friendly’ and ‘unfriendly’ witnesses to do so. ‘Friendly’ witnesses were given congressional immunity; their accusations stood unchallenged, and those who were defamed could not sue for libel or take legal action.”

At the same time, Blacklist does not shrink from certain truths. One panel states:

“The first political party in the United States to be racially integrated, the Communist Party of America (CPUSA) attracted members of racial and ethnic minority groups in part because of its civil rights platform, which fought against segregation and built alliances with a variety of progressive groups to oppose Nazis and Fascists.

“Jews had a long history of engagement with CPUSA through the Party’s work within the labor movement. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, many American Jews worked in the textile and garment industry, where questions of economic justice, safety, and inequality resulted in unionization. According to Communist Party historians, almost half of CPUSA membership was Jewish in the 1930s and ’40s.”

The aforementioned Mississippi John Rankin was always keen to list the birth names of Jewish actors and directors to indicate their Jewishness.

“In this era of political division,” wrote the Los Angeles Times in response to this show, “and considering the rollbacks of civil liberties in this country, the exhibition has urgent contemporary context.”

Prompted by wartime anti-fascist films that were seen to glorify the USSR, such as Mission to Moscow, the FBI started reviewing film content for Communist messaging as early as 1942. Its agents maintained files on movies they considered subversive. In 1947, the conservative film industry group Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals hired author Ayn Rand, a figurehead for conservative, pro-business, and capitalist ideology, to write a guide titled “Screen Guide for Americans” that tallied a list of topics screenwriters should avoid. A negative view of bankers, in particular, stood out as a big no-no. The mass media picked up this perspective.

“There is a tendency” in some Hollywood films, wrote Richard E. Combs in American Legion Magazine (Mav 1949), “to emphasize racial and religious intolerance, discrimination, poor housing, crooked politicians, and unemployment, and at the same time play down the priceless heritage of individual enterprise and cherished freedoms that our way of life affords.”

“We’ll have no more Grapes of Wrath, no more Tobacco Road,” said Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, “we’ll have no more films that deal with the seamy side of American life. We’ll have no more films that treat the banker as the villain.”

One of the rare instances of establishment pushback came from The Fund for the Republic, which published its perhaps somewhat belated “Report on Blacklisting” in 1956. It characterized “the very nature of the filmmaking process, which divides creative responsibility among a number of different people and which keeps ultimate control of content in the hands of top studio executives; the habitual caution of moviemakers with respect to film content; and the self-regulating practices of the motion picture industry…prevented such propaganda from reaching the screen in all but possibly rare instances.”

Panels and display cases treat such topics as “Hollywood (Briefly) Fights Back,” “The Clash of Directorial Titans,” “Naming Names,” “Navigating the Blacklist,” “Exile,” “Paul Robeson: Black and Blacklisted,” “The Clearance Machine,” “Media and the Mob Mentality.” Hazel Scott, Gertrude Berg (Molly Goldberg), and the film Salt of the Earth all get their own displays.

One panel on the 1960 film Spartacus, produced by its star Kirk Douglas, and directed by Stanley Kubrick with a screenplay by Dalton Trumbo, often cited as the film that broke the blacklist, unaccountably fails to mention its basis in blacklisted Jewish writer Howard Fast’s 1951 novel of the same name which he initially had to self-publish. It helped the film that the newly elected President John F. Kennedy publicly crossed an American Legion picket line to see it.

In an interactive section near the end of the exhibition, a dozen or so movie posters are displayed. Visitors are invited to open each panel to find a synopsis of the picture inside, with its Blacklist associations, and excerpts from its FBI file. The Boy with Green Hair, a 20th Century-Fox production from 1948, fell under the FBI purview because of its Blacklisted director (Joseph Losey) and screenwriters (Ben Barzman and Alfred Lewis Levitt), and also because the project had originally been meant for Adrian Scott, who had been fired by RKO before production began. The visitor can read excerpts from the FBI’s overview of the film, about a young orphan with a shaved head, whose hair grows back green, as a commentary on “the harmful effects of war on children.” “The Daily Worker,” the FBI reports, “reviewed the picture favorably… It cited an alleged parallel between the abusive treatment of the boy because of the color of his hair, and the discrimination against [Black people] because of the color of their skin.”

As the thematic palette of American films paled in the 1950s, to avoid complex characters and subjects, like racism, poverty, the economic struggles of returning veterans, and nuanced depictions of minority groups, the overall mission of the motion picture industry turned to promoting the “American way of life,” with “normal” consumerist families and romantic comedies. The openly anti-Communist films Hollywood created tended to be box-office bombs.

The media sponsor of this exhibition is The Hollywood Reporter. At the entrance to the show, a wall of Hollywood Reporter front pages from the era defines the growing impact of the Blacklist on the industry.

A 15-minute film The Hollywood Ten (1950) is screened in a small vestibule almost immediately across the corridor at the entrance to Blacklist. It belongs to the Skirball’s permanent installation, and is not part of the show. Unfortunately, many visitors will miss seeing it, because there’s no signage directing them to it. Attendees should make a point of viewing it. Distributed by The Film Division of the Southern California National Council of the Arts, Sciences, & Professions, this documentary features short speeches from each member of the Hollywood Ten. Pictured here are Adrian Scott with the CPUSA’s “cultural commissar” in Hollywood, playwright, and screenwriter John Howard Lawson.

Blacklist: The Hollywood Red Scare is on view through Sept. 3 at the Skirball Cultural Center, 2701 N. Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles 90049. More information about the exhibition and its related programming can be found here.