SAN DIEGO—“Horror takes the angst of being Black in America and gives it a space.” Those were the words of author, artist, and curator John Jennings, leading a San Diego Comic Con (SDCC) panel on his latest project, the horror comic anthology Box of Bones. The ten-part series, touted as “Tales from the Crypt Meets Black History,” mixes horror, history, and activism to relate a story that weaves together the painful past of racial oppression with the present conditions of a people still striving for true equality. The panel was presented by the Comic Arts Conference, a smaller conference held within SDCC that aims to take a more academic and layered approach to sequential (comic) art, and focused on the intersectional identity in the series as it relates to horror, alternative history, revenge and restorative justice.

Creator John Jennings was joined on the panel with series collaborators, letterer Damian Duffy, colorist Stanford Carpenter, and cover illustrator Stacey Robinson. The panel highlighted the genesis of the project, drawing on the impact of the African diaspora, systemic racism, and the Black experience.

The plot of Box of Bones concerns a Black lesbian graduate student, Lyndsey, who begins her dissertation work on a mysterious box. The box tends to pop up during the most violent and troubled times in Africana history. Her research on the object leads her on a surreal journey through the history of the Black experience, from West Philadelphia riots to Haitian slave uprisings. Chaos ensues wherever the box is found, and Lyndsey soon begins questioning her own sanity as she experiences these phenomena. The box contains monsters, each reflecting terror and stereotypes associated with Blackness.

The plot of Box of Bones concerns a Black lesbian graduate student, Lyndsey, who begins her dissertation work on a mysterious box. The box tends to pop up during the most violent and troubled times in Africana history. Her research on the object leads her on a surreal journey through the history of the Black experience, from West Philadelphia riots to Haitian slave uprisings. Chaos ensues wherever the box is found, and Lyndsey soon begins questioning her own sanity as she experiences these phenomena. The box contains monsters, each reflecting terror and stereotypes associated with Blackness.

Jennings explained that the idea for the project came from wanting to create a series based on the spoken word poem by famed writer Amiri Baraka, entitled “Black Dada Nihilismus.” “Essentially the theme of the poem is about the ‘make you want to holler moment.’ The moment when there is nothing left. The moment when there’s no justice. What does that moment look like in a box? That’s what the poem is about. It’s about transforming yourself into the thing that people say that you are. Transforming yourself into the other Black body that society [projects onto you],” the author explained. Citing how the genre of horror can be used to showcase that moment, Jennings said further, “The poem goes into those spaces, and a lot of times horror can be used to unpack those themes. [I decided] to take the traditional European pop culture aspect of horror and thought about what a Black horror space would look like.”

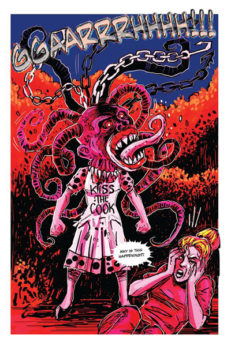

The Black horror space Jennings envisions makes for some terrifying creatures, as the author displayed the various monsters within the box and what they represent for Black people. “All the different archetypes are based on essentially taking Black stereotypes, or figures known within the Black community, and pushing them into the furthest extent in which they can go. You push it too far and it becomes horror. The abject,” Jennings explained.

One monster, called The Dark, designed after the pronged collar given to runaway slaves, is reflective of the Jim Crow era of United States history. Another monster called The Suffering, is the manifestation of the Black Buck, also known as the Brute, stereotype of Black men. The monster called Night Doctor is a symbol of medical oppression of Black people, such as the Tuskegee Experiment Syphilis Study in which Black men for years went untreated for syphilis in order for white doctors to study the effects. The Wretched monster is a lynching tree that captures people and makes them a ‘pickaninny,’ which is a racist stereotype of Black children. Jennings said that he believes his most horrifying and powerful monster is the one, in the form of a female body, that represents the tears of Black mothers. It embodies the suffering and pain of Black mothers who have lost their children to violence and oppression.

One monster, called The Dark, designed after the pronged collar given to runaway slaves, is reflective of the Jim Crow era of United States history. Another monster called The Suffering, is the manifestation of the Black Buck, also known as the Brute, stereotype of Black men. The monster called Night Doctor is a symbol of medical oppression of Black people, such as the Tuskegee Experiment Syphilis Study in which Black men for years went untreated for syphilis in order for white doctors to study the effects. The Wretched monster is a lynching tree that captures people and makes them a ‘pickaninny,’ which is a racist stereotype of Black children. Jennings said that he believes his most horrifying and powerful monster is the one, in the form of a female body, that represents the tears of Black mothers. It embodies the suffering and pain of Black mothers who have lost their children to violence and oppression.

Highlighting that this wasn’t their first time using horror to explore socio-political themes, Duffy cited one of his collaborative works with Jennings entitled “The Hole: Consumer Culture.” The story is a science fiction horror story about the buying and selling of race in America, and the simultaneous worship and degradation of African Americans in popular culture. Duffy explained that “Systems of representation, particularly mass media, and capitalism in general, strengthen and reify these stereotypes. A lot of those themes [in The Hole] parallel with Box of Bones.”

Jennings added that The Hole and Box of Bones are examples of an emerging “ethno gothic” trend, which takes horrific supernatural spaces in storytelling, and uses that trauma to unpack ideas around the horrors of racism and oppression. Jennings highlighted the book Infidel, which is about a monster that lives in an apartment complex and feeds off of xenophobia, as another example of this emerging practice.

“Horror merges how complicated, ugly, and terrifying race and gender is in this country,” Duffy said. “Horror allows you to go out into the spaces of the unknown in a way that other genres don’t,” Carpenter added.

Jennings noted that over twenty-five artists of different races, cultures, and generations worked on Box of Bones. The co-creator and writer of the series, along with Jennings, is Ayize Jaima-Everett. Everett is the creator of the series Liminal People. Jennings also highlighted the role of Black women in the series. “We wanted to disrupt the narrative [of the patriarchal space] by having the main two characters be women of color. We also have a lot of women of color behind the scenes on the project.”

Jennings emphasized that the story is not limited to one country or place. He explained, “Box of Bones isn’t just about the Black experience in North America, but the entire diaspora. The genesis of the box is on a slave ship.”

The first book of the Box of Bones series can be purchased on Comixology.

Like free stuff? So do we. Here at People’s World, we believe strongly in the mission of keeping the labor and democratic movements informed so they are prepared for the struggle. But we need your help. While our content is free for readers (something we are proud of) it takes money — a lot of it — to produce and cover the stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, can keep us going. Only you can make sure we keep the news that matters free of paywalls and advertisements. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by becoming a $5 monthly sustainer today.