NEW YORK—Dame Ethel Smyth was an early champion of feminism and equality. Deceased some 74 years now, she is finally achieving public consciousness in the era of #MeToo, Stormy Daniels, and the annual Women’s March.

The bitter irony is that this spokeswoman of democracy, women’s liberation, LGBTQ rights and radical cultural work has stood, at best, as a footnote of late-Romantic period British music. In her time, Smyth struggled against conservative music academics, as much as the flagrant sexism riddling paternalistic gentry, who sought to have her disavowed. Born just outside of London in 1858, Smyth was formally educated in English music colleges before traveling to Germany, where she embarked upon a close study of Brahmsian composition. Debuting several early works by the 1870s, Smyth earned critical acclaim and yet experienced the disdain of male musicians, culminating in the refusal by many to perform the works of “a lady composer.”

Smyth traveled throughout Europe over the last decades of the 19th century, ever independent, composing prolifically. Her works in this period included an opera, Fantasio, and her noted piece for chorus and orchestra, the Mass in D. She conducted her own music in the concert halls of Germany, France and Britain, breaking new ground in this decidedly male forum.

While in Florence Smyth first encountered Harry Brewster, an American expatriate with whom she would hold a powerfully, visceral bond. She called “HB” her soul-mate and greatest champion, and together they explored classical Greek dramas, contemporary French poetry and philosophy. Brewster helped her write the librettos of several operas but also embarked upon his own literary projects. Among these was an 1891 work of fiction, The Prison: A Dialogue, which metaphysically portrayed an innocently convicted man living out his final days in solitary confinement. Brewster died in 1908.

Smyth became a central figure in the British women’s movement, composing the theme of UK suffragettes, “The March of the Women,” in 1911. Inspired by the leading feminist Emmeline Pankhurst, she enthusiastically defied police orders during a rally for voting rights and was among a large group jailed for 60 days, convicted of throwing stones at the windows of Parliament. It is said that as her sister inmates sang the anthem, she conducted the proceedings through bars with a jail-issued toothbrush. Smyth was an active member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, a particularly radical branch of feminists, and spoke openly of her lesbian lifestyle, defying Tory hysterics.

The composer suffered crushing blows throughout her career, none more so than the hearing loss which greatly curtailed her role as conductor. She found new inspiration in the writing of essays and books and it was through this medium that she befriended Virginia Woolf, who also became a lover. In 1922, her artistic merits were finally acknowledged by the British government which granted her the Member of the British Empire honor and the title of Dame.

At age 72, in 1930, Smyth completed her last major composition, The Prison, a symphony for female and male soloists, chorus and orchestra, adapted from Brewster’s novelette. With this piece, she was able to symbolically realize the isolation she’d experienced throughout much of her life, but refused to be paralyzed by. And with advancing deafness, the remainder of Smyth’s existence was clouded by having to adapt to a more present inner world. Still, she was able to successfully conduct the world premiere of the piece at Edinburgh’s Usher Hall in February 1931, an act that must have given her the greatest sense of accomplishment: The silence which rapidly encroached upon her was here confronted by Smyth’s own resolve and core strength, much as the Prisoner character (the bass vocalist) and his Soul (the soprano) interact to an end most powerful and moving.

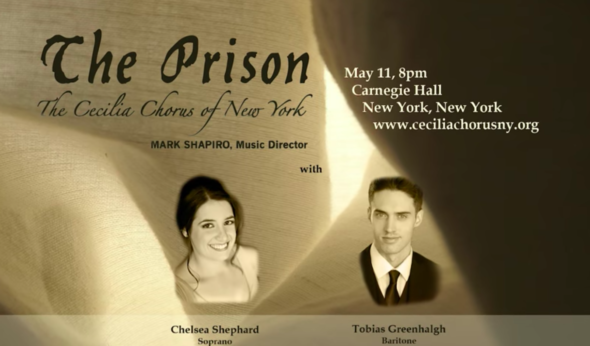

The Prison, with a text drawn from Harry Brewster, received a Carnegie Hall performance on May 11 by the Cecelia Chorus of New York, with orchestra conducted by Mark Shapiro. Baritone Tobias Greenhalgh and soprano Chelsea Shephard were the soloists. Dame Ethel is posthumously brought to the wider attention of what remains a male-dominated music industry.

The Prison is composed squarely in the late Romantic style, classically aligned, meticulously plotted, but painted with emotional flourishes associated with the back-to-nature philosophy of the latter 1800s. Bits of programmatic music, character motifs, antiphony and flowing counter-themes offer an atmosphere that represents both the protagonist’s sense of urgency as much as the confined stasis of the singular setting.

Throughout, the Prisoner and his Soul exchange thoughts which lead toward his realization of life’s beauty and majesty, even when marked by such repressive terms. “A great yearning seized me,” the Prisoner sings devoutly. “I would like to go out once more among the living! Can nothing of it all be good to others?” he ponders and asks what he would say to those existing freely. His Soul responds: “Tell them that no man lives in vain…,” a concept well rooted in progressive, humanist philosophy.

The role of the chorus, as designated by the Greek dramatists Brewster so admired, is narrative and speaks more to the audience than the characters down front. Acting as an aggregate higher power or perhaps the conscience of society itself, the Voices state: “We are full of immortality/This hour that is with us now/Will endure forever.” More so, the protagonist’s growth is exemplified in Part II, the morning, it would seem, of his execution. He exclaims: “I disband myself/And travel on forever in your scattered paths/Wherever you are there shall I be/I survive in you!/I set my ineffaceable stamp/On the womb of time,” an homage to collectivism that holds an endearing similarity to the final writing of IWW labor organizer, journalist and songwriter Joe Hill, unjustly executed in Utah seven years after Brewster’s death. Hill’s “Last Will” alerted his followers to his wishes for cremation, “And let the merry breezes blow/My dust to where some flowers grow/Perhaps some fading flowers then/Would come to life and bloom again.” John Steinbeck’s masterwork The Grapes of Wrath offers a still more poignant statement: “I’ll be all around in the dark. I’ll be everywhere you look. Wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there…”

It’s also useful to recall that the execution of the falsely accused anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, had taken place in 1927, only three years before Smyth completed The Prison.

Dame Ethel Smyth’s music accompanied the oppressed women of England in their struggle for a truly democratic voice. A composer of prodigious skill and talent, and a bold visionary in a time of profound reaction, Smyth’s rediscovery may have occurred at just the right time to inspire a new generation of feminist activists. On both sides of the Atlantic.

Comments