LONG BEACH, Calif.—South Korean Everywoman Hansol Jung is a director, playwright (with an M.F.A. from the Yale School of Drama), and lyricist. She has translated over thirty English-language musicals into Korean. I don’t know what her religious affiliation is, if any, but surely she is aware that a large percentage of the population in her country are ardent Christians. Her countryman, the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, was a right-wing religious leader vested in numerous profitable business ventures; with a mass following in his Unification Church who believed he was the messiah, he exemplified for many around the world the excesses of the ego-driven, prosperity gospel brand of Christianity now also common in America.

“Religion can do two opposite things,” she said in an interview. “It can destroy, hurt, and be an instigator of violence, but it can also be the only thing capable of controlling that violence.”

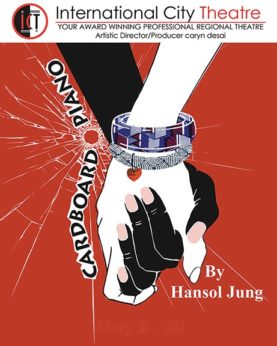

Showing her adventuresome spirit of casting far and wide for the subjects of her plays, Jung has set Cardboard Piano against the backdrop of the 30-year-long civil war in northern Uganda. Her harrowing drama confronts the religious and cultural roots of hatred and intolerance, as well as the human capacity for forgiveness and love.

The play, now receiving its Los Angeles County premiere in Long Beach, was developed during a residency at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center’s National Playwrights Conference, and premiered in 2016 in Kentucky as a part of the Humana Festival at the Actors Theatre of Louisville.

“I saw the premiere in Louisville and have chased the rights ever since,” says director/producer caryn desai. “This play is incredibly powerful and touching, and it’s relevant to so many issues we face in the world today.”

The two-act play begins in a church just after midnight on January 1, 2000. The new millennium has arrived and to the surprise of some, the world has not imploded. In a remote corner of Uganda, Chris (Allison Blaize), the impulsive 16-year-old daughter of an American missionary and his wife, is participating in a secret private wedding ceremony with a local teenage girl Adiel (Dashawn “Dash” Barnes), which they record on a cassette player. After the ceremony Chris has planned for them to elope to Tunisia, and from there Chris imagines they’ll find their way back to the U.S., where Adiel can receive professional schooling. Obviously, this all takes place before same-gender marriage was accepted anywhere.

But the ceremony is disrupted by violence when Pika (JoJo Nwoko), a 13-year-old child soldier fleeing the atrocities of war and the crimes of the local warlord—not named, but possibly Joseph Kony of the Lord’s Resistance Army, who sought to install a regime based on the Ten Commandments—stumbles in, wounded and scared, and flashing both a gun and a knife toward the two young women.

Chris and Adiel manage to calm Pika down, put some first aid on his lesion, and give him some comfort. Chris also provides redemption with the aid of techniques Chris is familiar with from the South African Truth and Reconciliation movement following the demise of the apartheid system. They record his confession, his repentance, and Chris’s forgiveness. (Her full name is Christina, but she prefers Chris. The Christ-ian significance of her name can not be incidental.) It all comes apart when Pika’s fellow soldier (Demetrius Eugene Hodges) comes searching for him and when Pika discovers that the two women who rescued him are lesbians!

The denouement unfolds in Act 2, which takes place in that same church in 2014. The traumatized Pika has now become Paul, fire-and-brimstone pastor. He is now in his late twenties, celebrating his second wedding anniversary with Ruth (played by Barnes), a beautiful young woman from the city who out of her love for Paul, despite his damaged past, has agreed to settle in this distant, isolated village. She pleads for a local man Francis (played by Hodges), who wants to stop by and see the pastor, but Paul doesn’t want him in his church. Suddenly out of the blue, Chris, now thirty-ish, appears from America, bearing her father’s ashes and seeking to bury them at this church where he had felt religiously most fulfilled. The reunion between Chris and Paul does not proceed smoothly, each of them bearing the scars of a decade and a half before.

Ruth asks her husband if Francis isn’t like the one lost sheep out of a flock of a hundred who needs Paul’s special ministry, but Paul rejects that saying the other 99 in this community are lost too! Repentance, it seems, is never complete, and new factors continually call into question the integrity of the redemption.

Uganda is one of those countries often visited by North American evangelicals who, seeing their anti-gay crusade fail at home, have flooded over to Africa, as well as to Russia, trying to convince governments there to pass stringent homophobic laws. We are not privy, of course, to the financial emoluments that may guarantee this persuasion, but we may presume them to be generous.

Uganda is famous for its severe so-called “Kill the Gays Bill” (the Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2014) which in its original iteration provided for the death penalty for LGBTQ people. In few African countries today is homosexuality generally tolerated. Even in South Africa, where LGBT rights are enshrined in the Constitution, and same-gender marriage is legal, repression against gays and lesbians persists.

A familiar old joke has it that the European colonialists brought the Bible to the Africans on the resource-rich land, and now the Europeans have the land and the natives have the Bible. This territory is explored brilliantly in Barbara Kingsolver’s novel The Poisonwood Bible.

I was struck by the complete originality of this play and its social relevance, not just to the African context but here at home as well, where under the Trump administration, many advances made by the LGBTQ movement have fallen under the menacing gaze of the White House. Before the end of June we shall hear from the Supreme Court—now packed unconscionably with the right-wing Neil Gorsuch after the Senate refused to allow President Obama a rightful nomination—in the Cakemasters case, whether or not “religious freedom” in this country now means the unrestrained freedom to impose your religious beliefs on any customer, client or patient who walks through the door of your business. I might have wished for the connection between American evangelical homophobia and African anti-gay attitudes to be spelled out more explicitly, but it was faintly implied and not necessary dramatically.

As, in his own words, the “openly gay, first generation Nigerian American” actor JoJo Nwoko says in an interview with Rage Monthly, “Pika is a pastor who believes religion has erased the awful things that have happened in his past. Someone knocks on his church doors one day, who brings back all of the demons he thought he’d gotten rid of. Like the saying goes, you can run, but you can’t hide.”

After all the fraught tension has exploded, in this challenging play with four actors and six characters, will it dissipate, or will the cycle of hatred simply reproduce its venom from generation to generation? Does forgiveness mean the same thing for the forgiver and the forgiven? Perhaps not.

The set design by Yuri Okahana is an effective open wooden structure. Donna Ruzika provided the lighting design, and Kim DeShazo the costumes. The song “Unchained Melody”—“I need your love, God speed your love”—plays a critical role.

Cardboard Piano runs Thurs., Fri. and Sat. at 8 pm and Sun. at 2 pm, through May 20, at the International City Theatre, located in the Long Beach Performing Arts Center at 330 East Seaside Way in Long Beach 90802. For reservations and information, call (562) 436-4610 or go to the theatre website. This play is recommended for mature audiences, ages 16 and up.