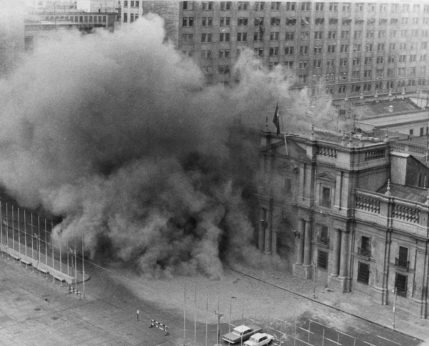

On the morning of September 11, 1973, , British-made Hawker Hunter jets bombed La Moneda presidential palace in Santiago, Chile. Hours later, Chile’s elected head of state, President Salvador Allende, was dead.

Soldiers raided working-class districts across the country rounding up left-wing activists. Around 40,000 were incarcerated in Chile’s National Stadium, awaiting interrogation. Many faced torture and imprisonment, others execution. Hundreds of other militants simply “disappeared.” Allende’s government of Popular Unity was replaced by a military junta headed by General Augusto Pinochet.

The experience of Popular Unity and its dramatic and bloody end is dealt with in a new book from Praxis Press, 1000 Days of Revolution. This book contains nine chapters, each one written by a prominent Chilean communist as part of their party’s attempt to self-critically analyze the weaknesses of Popular Unity. These articles were originally published in the Prague-based World Marxist Review and subsequently published as a book in 1978.

The Chilean experience was a sustained attempt to advance to socialism through a non-armed strategy based on a constitutionally elected government. Popular Unity’s failure has often been taken by its leftist critics as definitive proof of the impossibility of any such path.

Other commentators from the then-powerful Eurocommunist current drew opposite conclusions, stressing instead the need for a purely “democratic road” to socialism, one that would seek compromise and consensus between mass political forces and traditions rather than through the intensification of class conflict.

The conclusions reached in this volume reject both these viewpoints. Specifically, they stress the confirmation of two fundamental insights of Marxism.

First, that the left cannot simply take over the existing machinery of government and the state from the existing ruling class and use it for different ends. Second, that no successful revolutionary movement can succeed unless it can consolidate and maintain a political majority in society.

Leftist critics of Popular Unity tend to emphasize the first factor, reformist critics the second. In reality, they are complementary elements and are fused within all revolutionary processes. Popular Unity’s defeat was due to the failure to resolve these questions.

Key economic changes by Popular Unity, above all the nationalization of the copper industry, sent shock waves to Wall Street and the White House, where they feared that the Chilean experiment would be repeated elsewhere unless it was stopped—at any cost.

Starting with just 36 percent of the vote in the 1970 presidential elections, Popular Unity faced constant challenges to create and sustain a political majority. This was not an arithmetical challenge but a political one, as communist theoretician Volodia Teitelboim stressed.

“We have said that the peaceful path is practicable only if the idea of the revolution wins the minds of the majority of the people and prompts it to act. When the forces favoring change have achieved overwhelming superiority, no opportunities are left for a reactionary rising, let alone for its success.”

The creation of Popular Unity was a remarkable achievement, bringing together Marxists, radicals, secularists, and Christians. However, as Gladys Marin points out in her chapter, “one of the main problems of the Chilean revolutionary process was that no solid and homogeneous revolutionary leadership was brought into being.”

The unity of the Communist and Socialist parties was more highly advanced and longer established than in most other countries. Nonetheless, differences of emphasis, pace, and direction emerged; sometimes these were successfully resolved, but at other times they became a source of friction.

The nature of the Chilean revolutionary process itself was debated. While many in the Socialist Party and other left groups saw Chile as undergoing a fully socialist revolution, the Chilean Communists categorized the initial stage of the revolution as being “national-democratic.”

This meant that to begin with, revolutionary measures should be directed not against private property in general but focused instead on foreign imperialism and the domestic oligarchy, whose monopolistic exploitation of the economy set them not only against the working class and peasantry but also against the middle strata and even sections of the smaller bourgeoisie.

Efforts had to be made to either win these forces or at least to neutralize them.

The Christian Democrats took over a quarter of the votes (28 percent) in the 1970 presidential poll and were influential among these middle strata. They retained significant working-class influence, with just over a quarter of the total votes cast in the main trade union federation in 1972, but its leadership also had close ties to big business.

The vacillation of the middle strata is also illustrated by the fact that two successive left splits from the Christian Democrats, MAPU in 1969 and the Christian Left in 1972, entered Popular Unity.

Traveling in the opposite direction, the Radical Party suffered right-wing splits to the opposition.

Initially, the Christian Democrats confirmed Salvador Allende’s presidency and supported the nationalization of the copper industry. However, by 1973, the Christian Democratic leadership had allied with the far-right National Party.

Despite mounting difficulties, the March 1973 parliamentary elections saw Popular Unity win 44 percent of the vote, preventing the right-center bloc winning the two-thirds parliamentary majority needed to oust Allende.

Orlando Millas writes: “At a time when we had won power only in part, it was essential to democratize every field of activity, to carry out far-reaching democratization measures in economic management, extend democracy to the judiciary and the control machinery, achieve a balance of forces in favor of democracy among the military, and bring the administrative system into line with genuinely democratic standards.

“We stopped halfway in this respect. The Popular Unity government failed to establish effective democracy in decisive fields. Its gains, while impressive and highly noteworthy, were clearly inadequate.”

In Washington, the “40 Committee,” consisting of President Richard Nixon, National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, CIA representatives, and others, met to discuss U.S. interference in Chile.

Pedro Rodriguez notes: “In Chile, imperialism did its utmost to destabilize the popular government. Economically, it resorted to a financial and technological blockade. With the help of Chile’s financial clans, it mounted desperate opposition inside the country, boycotting production, leaking currency abroad, and speculating in capital.”

Once electoral defeat of Popular Unity had proved impossible, the counterrevolutionary forces turned decisively towards military action.

In the view of Teitelboim, “‘Peaceful transition’ is a correct term only in so far as it rules out civil war, but because of the many vicissitudes, it cannot bypass the law which says that violence is the ‘midwife’ of history.

“We should have always borne this in mind, should have remembered that the very act of changing path presupposes ‘changing horses’ and continuing our advance.”

The downfall of Popular Unity was first and foremost a political defeat, the later military blows came only once the political atmosphere had been created that allowed the coup to succeed.

Communist Party of Chile General Secretary Luis Corvalan remarked: “Since 1963, the party had been giving its members military training and making efforts to acquire enough arms to defend the government that we were confident the people would set up, but this was not enough, because our activity in this direction was not accompanied by the main thing, namely persistent and sustained propaganda to give the popular movement a correct attitude to the military.”

It would be wrong to take Chile’s experience in 1970-73 as illustrating every possible challenge that left governments will automatically face from the right. There are, nonetheless, sufficient common features to encourage today’s generation of activists to study the past. 1000 Days of Revolution sets out to do that.

1000 Days of Revolution: Chilean Communists on the Lessons of Popular Unity 1970-73, will be published later this year by Praxis Press in the UK. They can be contacted at praxispress@me.com.