In his presidential campaign, Donald Trump adopted a very hostile anti-China tone. However, after assuming office, his actions toward China proved largely a continuation of established policy. Why? What are the prospects for the future of the U.S.-China relationship?

In his campaign, Trump elevated the now standard anti-China rhetoric of both Democrats and Republicans to a new level. He blamed China’s supposed cheating approach to trade for swindling the U.S., resulting in trade deficits and job loss. He said he would declare China a currency manipulator and spoke of applying a 45 percent tariff to Chinese goods.

Shockingly, he took a congratulatory phone call from Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen and referred to the One-China policy, the foundation of U.S.-China relations for 40 years, as a “bargaining chip.” Rex Tillerson, the nominee for secretary of state, said China should be denied access to its new installations in the South China Sea. If implemented, this approach would have yielded a rapid deterioration in U.S.-China relations.

After the new administration took office though, much of this rhetoric evaporated. The One-China policy was reaffirmed, and after a review, the U.S. announced that China was actually not a currency manipulator. There was less chance of military confrontation in the South China Sea. U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership reduced economic pressure. Secretary of State Tillerson, during a visit to Beijing, dropped the anti-China talk and even repeated some of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s favorite rhetoric, calling for cooperation, non-confrontation, and mutual respect.

Why did the new U.S. administration moderate its position?

Splits in capital

U.S. capitalism, since the 1980s, has been relatively ambivalent in its attitude towards China. While all sectors of capital would probably like to see regime change in Beijing leading to a more U.S.-compliant government, there are a number of strategies at work.

With the expansion of China’s private sector in the 1980s, U.S. corporations have made big profits in China, and many companies like Boeing, Apple, GM, and Ford have major commitments there. Wall Street banks seek to penetrate Chinese markets, thus leading them to support normal relations; their strategy is one of soft power. They think that liberal values and practices like democracy, human rights, freedom of speech, direct elections, and consumerism will appeal to youth, grow a new middle class, and undermine communism. The U.S.’ role, then, is to support Chinese elements who will oppose and eventually topple the Communist Party of China and institute Western-style political institutions.

Other sectors of U.S. capital, however, see a rising China as the fundamental threat to U.S. global hegemony. This group focuses on long-term strategic considerations, is more ideological, and is less concerned with immediate corporate profits. It backs the “pivot” to Asia, or the encirclement of China with bases and alliances. U.S. support for reviving militarism in Japan and installation of an anti-ballistic missile system in South Korea are elements of this approach.

The Chinese government has adopted a wait-and-see attitude towards Trump, responding not to his talk but to his actions. President Xi is willing to negotiate trade but will not change his position on core issues bearing on national sovereignty. If Trump wants to more productively engage with China, he should study up on its history and recent development. Which segment of U.S. capital will win out in shaping his policy is still an open question.

Roots of China’s foreign policy

To understand China’s foreign policy, it is necessary to know some basic history. China was for many centuries the dominant power in East Asia. This changed in 1839-42 as British naval power defeated China in the First Opium War, beginning the “century of humiliation.” China subsequently lost a series of wars to Britain, France, and Japan and lost control over its coastal seas, culminating in the U.S. Seventh Fleet asserting dominance over the Taiwan Straits in 1949, thereby enabling Chiang Kai-shek to seize power in Taiwan.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai repeatedly expressed the desire to have friendly relations with the U.S. But with the Korean War in 1950, Chinese troops, in alliance with the Soviet Union, fought the U.S. to a bitter stalemate.

China’s foreign policy has long been based on what the government refers to as the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, jointly issued with India in 1954 and adopted by the Bandung Conference in 1955 by the non-aligned movement: 1) mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; 2) non-aggression; 3) non-interference in internal affairs; 4) equality and cooperation for mutual benefit; and 5) peaceful coexistence.

Major ideological and policy disputes led to the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s, but eventually China began to emerge from its Cultural Revolution isolation to advance its “Three Worlds Theory” in 1974. This targeted both U.S. imperialism and “Soviet social-imperialism” and sought to position China as leader of the Third World. However, China’s strong anti-Soviet stance often led to alignment with U.S. strategy and produced confusion in national liberation and left-wing movements globally.

Deng Xiaoping, coming to power after Mao’s death, adopted the “crouching tiger” approach – lie low, build up strength, don’t take leadership. This was during China’s period of rapid industrialization and trade expansion based on low wages, exports, and encouragement of foreign investment. Paramount, according to Deng’s strategy, was the need to build a strong economy and advanced technology. Friendly relations with Japan and the West were the priority at the beginning, although eventually China became a huge trading partner with many countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The speed of China’s expansion was facilitated by its “no strings attached” trade and investment policy, which makes no political demands on developing countries, in contrast to the IMF, World Bank, and Western countries which pressure for neoliberal policies, structural adjustment, and austerity budgets.

Today, “crouching tiger” has been replaced by “China’s peaceful rise,” introduced by President Hu Jintao in 2005. Beijing wants a peaceful global environment to enable its continued economic and social development. It thus opposes hegemony and supports the trend towards a multi-polar world. This means commitment to multilateral institutions such as the United Nations, the G77 plus China, the G20, the Shanghai Cooperation organization, and BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

President Xi Jinping has called for a new type of “win/win diplomacy” where cooperation is primary and relations based on mutual benefit. Increasing globalization is the long-term trend but it must be inclusive and not controlled by corporate interests.

China’s foreign policy is thus based on lofty ideals which overlap with peace movement sentiment. Like most developing countries and people of the world, China wants economic and social development, not war.

“Belt and Road” and other new international initiatives

The new Chinese-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) may have been boycotted by the U.S., but most Asian and European countries, including the U.K., are participating.

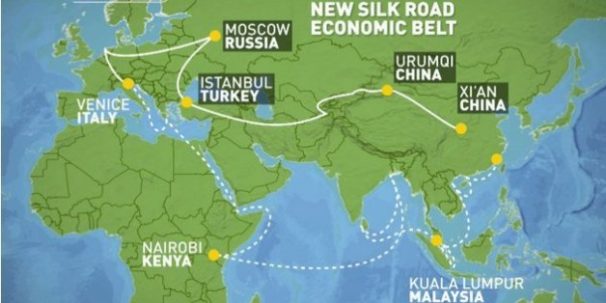

The bank is helping finance a major new international economic effort: the ambitious “Belt and Road” initiative. Launched in 2013, this plan includes large-scale cooperative development and infrastructure projects involving dozens of countries in Southeast and South Asia, and west to Central Asia and Russia, to the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and the east coast of Africa.

Favorable financial terms are extended through the Silk Road Fund and the AIIB. At an international meeting in May, Xi announced $100 billion worth of projects with eventual total investment projected at one trillion dollars. The Belt (overland through central Asia) and Road (new maritime silk road leading from Southeast Asia across the Indian Ocean), if successful, will considerably strengthen China’s international economic influence as well as bolster development in its own poorer interior provinces. It is one part of China’s huge program of investment in the developing world.

The Obama administration initiated the U.S.’ “pivot” or rebalancing to Asia-Pacific, often seen as a strategy to thwart a rising China. China is modernizing its military, however, with a new emphasis on coordinated air and sea operations and the ability to fight and win local high-tech wars. In part, this is a response to the U.S. military buildup.

China is also reasserting what it sees as its traditional position in the South and East China Seas. Tensions have decreased in 2017 as Asian countries are moving towards negotiations and avoiding confrontation, but China’s neighbors are very aware of the long history of Chinese regional domination.

China is modernizing its arsenal of nuclear weapons, which consists of about 300 nuclear warheads and long-range ballistic missiles. The Chinese have a no-first-strike policy and advocate nuclear disarmament; however, they also feel that the largest and most aggressive nuclear superpower, the United States, should take the lead in the disarmament process.

China has just one overseas military base, a refueling station in Djibouti to help with patrols against pirate ships off the coast of East Africa. The Chinese have no formal military alliances, although in recent years there have been large-scale joint military exercises with Russia.

China is a signatory and strong supporter of the Paris Climate agreement. While still the world’s number one emitter of greenhouse gases, and plagued with a bad smog problem in major cities, the Chinese have been gradually reducing their dependency on coal and have committed to generating 20 percent of their energy from renewable resources by 2030.

The government invests in renewables on a large scale and the country has the world’s biggest installation of solar and wind energy. Many feel that China will have an opportunity to be a world leader in fighting climate change, especially as the Trump administration has backed out of the Paris agreement.

Domestic shifts

Shifts in domestic policy also affect China’s outlook on the world. Today, it has a mixed economy, with socialist and capitalistic sectors, but is moving in the direction of more socialism, according to the Communist Party. The move towards strengthening socialism has been pronounced since the 2008 global recession. While growth has slowed, this is in part deliberate, due to the shift to a different economic model, the “new normal.”

Moving away from an export-oriented, low-wage strategy, China is now developing a more mature, innovation-driven, service-oriented economy, with emphasis on building domestic consumption and government services, rather than export manufacturing, as drivers of growth. China still refers to itself as being in the first or primary stage of socialism, planning to achieve a moderately well-off society by 2021 and a developed socialist country by 2049.

The Communist Party will convene its 19th Congress this fall, which will be a time of political maneuvering as a new leadership group is elected. Xi Jinping, recently named as a “core leader,” appears to be in a strong position. Under him, politics have shifted to the left, if viewed from a Western viewpoint; for example, there is more discussion of core socialist values, emphasis on Marxism-Leninism in education, and more critique of bourgeois Western influences. The leading role of the Communist Party has been affirmed. In foreign policy, Xi’s orientation has tilted toward the developing world and Russia, rather than accommodating the West and Japan for export markets.

Former Communist Party General Secretary Hu Jintao, at his 2012 speech summing up ten years in office, identified problems within the party itself as the biggest threat to its support among the people and thus its ability to continue in power. In addition to illegal activities such as bribery and nepotism, there are serious problems of bureaucratism, arrogance, and excessive perks among officials – all resented by the people. Soon after taking office in 2013, Xi Jinping launched a popular anti-corruption campaign which has seen the prosecution of many officials.

Xi often stresses the importance of “core socialist values” as the ideological and moral foundation for China, amid concerns the country has lost its way during the three-decade economic boom. Corruption, alienation, and other social problems have intensified, with increasing individualism and crass consumerism.

At a December 2016 conference, Xi strongly reaffirmed the supremacy of Marxism and socialism in Chinese institutions of higher learning. The greater emphasis of Marxist teachings has led to greater funding for research bodies such as the Academy of Marxism of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

China’s rising: Unique in the world

China is a unique country: A 4000-year-old civilization that saw feudalism give way to both democratic and socialist revolutions in the 20th century, followed by a historic program of rapid industrialization. Today, China still has the world’s largest population and industrial working class, as well as an 89-million-member communist party.

Its continuing rise will be one of the most important features of the 21st century going forward. As for Americans, they are impacted not only by Chinese-made products but also by growing Chinese job-producing investments in the United States. Chinese companies now own billion-dollar enterprises such as AMC theaters, GE’s appliance division, Motorola mobile phones, Smithfield foods, as well as New York’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel. Together, they account for around 100,000 U.S. jobs.

China rose from the relative isolation of the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s to be the world’s largest trading country today, as measured in total value of imports and exports. One of the largest recipients of foreign direct investment starting in the 1980s, China is now the largest source of investment funds in the developing world, surpassing the World Bank and Western institutions. Its military modernization is beginning to challenge U.S. dominance in its coastal regions. Chinese influence in international relations is also increasing with an activist orientation in the United Nations, the Paris Climate Accord, and international bodies such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

China is also rebuilding a center for the world’s working class parties. For example, the World Socialism Forum is held in Beijing in October. The World Association for Political Economy in Shanghai publishes the World Review of Political Economy and organizes international conferences; the 2017 conference is in Moscow. Xi Jinping’s The Governance of China was published in English and distributed in U.S. bookstores, and exchange visits by Chinese Marxist scholars are becoming more frequent.

China is not well understood by the left, progressives, or the U.S. general public. U.S. mainstream media, quite positive in the 1980s when the government was expanding the private market, is now mostly one-sided and negative during a period when socialism is strengthening. A balanced perspective is needed, telling both sides of China’s complex and often contradictory reality. Socialists and communists too need to study socialist construction from the Chinese perspective.

Conclusion

The pursuit of dominance by U.S. imperialism in the context of declining capitalism will sharpen global class contradictions and tensions with the developing world. The capitalist United States could directly oppose the People’s Republic of China, the product of a socialist revolution. The Pentagon a few years ago created a contingency plan for war with China, called “air/sea battle.” Such a war is considered quite possible by those who favor U.S. hegemony and see China as the main obstacle. Such a war would be a disaster for the U.S., leading to economic dislocation and political repression.

The left and progressives should work for peace and friendship with China as a basic part of a democratic U.S. foreign policy. Socialist and working class organizations should actively pursue international contacts. We should oppose militarism at home and abroad, cut the military budget, and support international cooperation and the building of a multipolar world. There are vast possibilities for mutual exchange which would enrich Western, Chinese, and world civilization.