While media attention on South American politics has lately focused on Venezuela and Nicolás Maduro’s recent announcement of his intention to run for re-election, Venezuela’s neighboring country, Colombia, is set to hold its 2018 presidential elections in May, a political event with far-reaching repercussions that should not be underestimated.

Long hailed as one of the most stable democracies in Latin America, Colombia has been a textbook example of a country entirely controlled by the private economic interests of its established, conservative oligarchy, whose political members have not lost an election since 1946. Ever since, political power in Colombia has been the stronghold of traditional conservative and neoliberal politicians, whose economic policies have created what is today the seventh-ranked country in the world with the highest income inequality (first-ranked in South America), the country with the longest internal armed conflict on the whole continent, and one of the world’s leading illegal drug-producing and -trafficking centers.

To top it all off, Colombia is still today the leading South American political and economic ally of the United States, recipient of military aid that has amounted to more than $5.5 billion since the year 2000 and seven U.S.-operated military bases scattered all through its national territory. One could thus say, without fear of exaggerating, that Colombia’s leading political oligarchy depends in great part on the United States for its continued survival.

The favored candidates to win the 2018 presidential are a clear reflection of this. Iván Duque, the official candidate of the Centro Democrático party, has launched a multi-million-dollar campaign backed by former ultra-right wing President Alvaro Uribe, whose suspected ties with paramilitary groups have been repeatedly denounced by respected journalists such as Germán Castro Caycedo and by leading politicians of alternative political parties such as Iván Cepeda and Gustavo Petro.

A former law student at Sergio Arboleda University (Bogotá) and former Public Policy master’s student at Georgetown University (Washington, D.C.), Duque represents the age-old economic interests of the the biggest landowners and magnates of Colombia, with proposals ranging from lowering taxes for the rich to canceling the peace treaty that current President Juan Manuel Santos achieved with the FARC (the former rebel Revolutionary Armed of Forces of Colombia and now the legal Alternative Revolutionary Force political party). As a side note, it is worth remembering that it was Alvaro Uribe who, during his second presidential term (2006-10), strengthened the United States’ military aid programs in Colombia, by allowing more than $463 million to enter the Colombian military with the blessings of former U.S. President George W. Bush.

To international observers, it may be something of a shock to hear that the favored political party to win the upcoming presidential elections has explicitly promised to “tear down” a peace treaty that has promised to end more than fifty years of violence caused by the Colombian state’s military forces, illegal paramilitary groups, and former armed rebels whose leaders have now vowed to abandon violence to become a legalized political party.

But this shock will come as no surprise if one keeps in mind that Colombia’s main national media outlets (including the nation’s only public TV channels) are fully owned by the country’s traditional oligarchies, who have for decades propagated the myth that the violent conflict in Colombia has mainly been the responsibility of leftist guerrillas, even after the UN declared that 80 percent of all civilian killings during the country’s decades-long conflict have been caused by right-wing paramilitary groups.

It has thus become clear why defending democracy has become the main ideological staple of an oligarchy that has controlled virtually every aspect of democracy itself since the 1940s, from the most powerful news media outlets to the Congress seats and the presidential seat itself. If anything, Colombia has become a clear example of what happens to a nation when its public interests are sacrificed for the private economic interests of its centuries-old ruling oligarchy, and that is that democracy itself no longer exists because any alternative political movements are immediately erased from the public sphere for lack of funds and lack of true participation in the country’s public media.

With four months left until the presidential elections, Colombia’s present and future consequently look very bleak. The only other favored candidate to take the presidency is Germán Vargas Lleras, a conservative politician with neoliberal tendencies who is a member of the corruption-ridden Cambio Radical political party, and whose connections with Colombia’s mining magnates and richest landowners have been extensively documented.

After Lleras, self-proclaimed centrist candidate Sergio Fajardo has recently had good results at the voting intention polls, a phenomenon one should not get too excited about since Fajardo’s true colors have been revealed by the fact that he has the complete financial support of Antioquia’s Corporate Guild, and by the fact that his proposed policies range between—again—lowering taxes for the rich and raising citizens’ legal ages to apply for a pension, two trademarks of conservative, neoliberal thinking that have not shown any positive results since the 1980s (the period in which Colombia fully gave itself to the theories of the Chicago Boys school of economics).

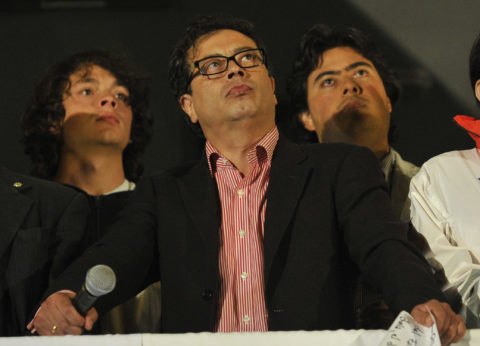

At the end of this long, dark tunnel stands Gustavo Petro, former mayor of Bogotá, who has launched a presidential campaign under the slogan “Colombia humana” (“Human [or humane] Colombia”) and who is now supported by alternative leftist parties such as Unión Patriótica and Movimiento Alternativo Indígena Social (Social Alternative Indigenous Movement), among others.

Petro, unlike the aforementioned candidates, has proposed policies that include state-sponsored universal health care and education systems, a gradual but permanent switch toward sustainable economic policies and a continuation of a strengthened peace treaty with the FARC. Even though polls have continuously shown Petro as one of the favored candidates in the upcoming election, his real chances are dim against the wealth and power of Colombia’s traditional political parties, which is why he has continuously tried to build an alliance with all the peace-supporting candidates to no avail.

Petro, one of the first politicians in the country’s history to publicly denounce links between paramilitaries and many of Colombia’s most powerful politicians, has repeatedly declared that peace without social justice will fall apart on its own. And to judge from the recent reports of two former FARC members killed in cold blood in Antioquia by right-wing assassins, his words are chronicling a disaster foretold for Colombia’s future.