“He was Julius before Julius. He was Elgin before Elgin. He was Michael before Michael. He was simply the greatest individual player I have ever seen.” – Larry Brown, longtime pro and college coach

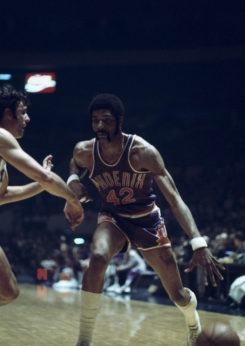

The first and only time I saw Connie Hawkins in person was on March 26, 1973, in Oakland. He spent the entire evening mopping the floor with Rick Barry of the Golden State Warriors. The “Hawk,” as he was affectionately called, took Barry to the hoop time and time again. Barry was helpless.

At the final horn, the Phoenix Suns beat the Warriors 120-114. Hawkins had torched Barry for 29 points, 10 rebounds, 7 assists, and made 12 of his 16 field goal attempts. Barry was no slouch; he was eventually named one of the 50 greatest players in NBA history.

And if Connie Hawkins hadn’t been blacklisted by the National Basketball Association and lost six years of his playing career for a crime he didn’t commit, he would be on that list, too

A black man being wrongly accused and having years of his life taken away isn’t exactly news in America. As a result of new evidence coming to light and DNA testing, many black people are being exonerated daily after having spent years behind bars.

Connie Hawkins didn’t spend time in prison. He spent eight years doing what he did best in front of tiny crowds in old arenas and on schoolyard basketball courts, where he had been a high school legend. His story might have had a hopeful beginning and a happy ending, but the middle was the stuff of tragedy.

Cornelius Lance Hawkins grew up in the Bedford-Stuyvesant (Bed-Stuy) neighborhood of Brooklyn in the 1940s and ’50s. He lived in a small two-bedroom apartment with his mother, father, four brothers, and a sister. Without enough money to buy beds for all the children, Connie and his two younger brothers shared a single sleeping cot.

During summer months, the heat was stifling in their apartment, so the kids spent all day outside playing stickball or basketball or running with the gangs. Connie was shy and felt awkward because of his body. At ten years old, he was already 5’10” weighing only 115 pounds. He tried to avoid confrontations, so, fortunately, gang life was never an option—but basketball was.

It wasn’t just his height that gave him a physical advantage. He had huge hands which allowed him to have better control of the ball, and as he grew, it wasn’t long before he could palm the ball, gripping it with one hand like a baseball.

Hawkins soon became one of the best players in the neighborhood, and when Boys High, a hoops powerhouse in New York City, came calling, he jumped at the opportunity. He sat on the bench for his sophomore season, but as a junior his game blossomed, and he was named to the All-City team. “I can’t explain how wonderful that felt,” he recollected. “I was finally good at something. So I started to really work at basketball, not just play it. I grew to love the game. For me, it became like a girl you can’t live without.”

In his senior year, Boys High won the city championship, and Connie was voted New York City’s top high school player. Dozens of college recruiters offered Connie money to play for them. They didn’t care if he was a good student or not (he wasn’t), they just wanted him to play basketball. After being flown all over the country, visiting campuses, and hearing how much each school would pay him, Hawkins decided on the University of Iowa.

“They seemed like nice people,” he said, “and they offered me the most money.” It looked like the dream of showing off his basketball skills against top-flight college players was about to come true.

But Iowa was like being on another planet. All Connie knew was Bed-Stuy, and Iowa wasn’t anything like that. There were only a few black athletes on campus, though they tended to be older and he wasn’t very comfortable around them.

He had virtually no social life and struggled mightily in his classes, as he hadn’t been prepared for the rigors of college coursework.

Because there was a rule then that freshmen couldn’t play on a varsity team, Hawkins was only able to scrimmage against other freshmen. The athletic department told him that he needed to get better grades if wanted to stay at Iowa.

Connie’s world turned upside down when a New York police detective came out to Iowa and told him he had to answer some questions back home. Connie had no idea what was going on, so he went back with the detective.

A huge investigation into point-shaving by college athletes was underway, and someone claimed Hawkins had introduced several players to gamblers. Nothing of the kind ever happened, but that didn’t matter to the New York City District Attorney’s office. Connie’s alleged actions were considered to be just as bad as the players who actually shaved points.

While never charged with a crime, Connie, an 18-year-old kid, was given immunity but had no idea what it meant—his name being linked to the point-shaving scandal meant that he had become a basketball pariah.

Iowa didn’t want him back, and no other college would touch him. It looked like Connie Hawkins would never escape Bed-Stuy.

And then came Abe Saperstein, founder and owner of the Harlem Globetrotters, who created the American Basketball League (ABL) after being turned down twice by the NBA for a a franchise team bid.

The ABL’s Pittsburgh Rens owner Larry Litman had heard about the playground exploits of a gangly 19-year-old Brooklynite and didn’t care about the rumors surrounding him. Litman flew Connie out to Pittsburgh for a tryout, and not five minutes into the scrimmage, the Rens’ coach turned to Litman and said, “This kid could be the greatest ever…sign him.”

Hawkins turned out to be the greatest player in the inaugural season of the ABL, leading the league in scoring with a 27.5 average and being named Most Valuable Player. But attendance at Rens games was so low that the team almost folded at the end of the season, and it took a new owner to come in and keep the franchise alive.

But the ABL itself was on life support, and halfway through the 1961-62 season, it ceased operations.

Connie was unemployed, but not for long. Saperstein offered him a contract to play for the Globetrotters. Hawkins took the offer and toured with them until 1966 when they let him go.

Back in Bed-Stuy again, Connie made some money playing in local tournaments and continued to enhance his legendary status as one of the best players in the country. He routinely outplayed stars from the NBA, but it still didn’t get him back into professional basketball.

That would happen with the creation of the American Basketball Association in 1967. Hawkins was signed by the Pittsburgh Pipers, and he dominated the ABA’s 1967-68 season, just as he had done in the ABL, leading the league in scoring, finishing second in rebounds, and winning another MVP trophy.

Although the Pipers won the ABA title, no one in Pittsburgh seemed to care, and the team relocated to Minneapolis, where attendance would end up being worse than it had been in Pittsburgh. It was a shame that so few people saw Connie emerge as the team’s leader as well as its best player. He was averaging 34 points per game when he injured a knee in January. It bothered him for the rest of the season, and he was worried that it might jeopardize his career.

While Hawkins had been spending the past eight years playing in half-filled arenas and neighborhood tournaments, his lawyer David Litman had been working to get him the opportunity to play in the NBA. The league continued to insist that Hawkins hadn’t been banned, it was just that no team wanted to draft him.

That was shown to be a lie when it was learned that the St. Louis Hawks, New York Knicks, and Los Angeles Lakers had all told NBA commissioner Walter Kennedy that they were interested in drafting Connie. But Kennedy told them that “there was some question in my mind about his desirability to play in the National Basketball Association.”

Now it had become obvious: Hawkins had been officially blacklisted because of his alleged contacts with gamblers.

The league relented after realizing the millions they stood to lose if Hawkins’ won in court, and the Phoenix Suns signed Connie to an NBA contract. When he got the news, he wept and said, “The NBA, the NBA, after all these years.” Now he could finally show the world how good a player he was.

The year before Hawkins arrived was the Suns’ first season as an expansion team, however, and they were awful. They finished in last place, lost money, and—most depressing of all—lost the coin flip for the right to draft Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who would go on to be the all-time leader in points scored in the NBA.

But not everything looked bleak; the Hawk was coming to town.

While everyone knew Connie was the best player on the team, he wasn’t getting the ball as much as he should have. The offense went through Gail Goodrich, the white starting point guard, who looked for his own shot first rather than finding the open man. Hawkins and Paul Silas, the Suns’ power forward, knew that whether consciously or unconsciously the coach was deferring to the white players on the team and that obviously didn’t sit well with Connie and the other black players.

The Suns’ play didn’t help; they weren’t winning and had at one point lost seven games in a row. The team held a “players only” meeting that was tense but productive until a fight between Hawkins and Goodrich almost broke out. From then on, Goodrich got the ball to Connie more often and the team started winning.

But not for long.

General manager Jerry Colangelo knew that something had to change. Now even the white players were unhappy with the coach. So he fired the coach and took the job himself, in addition to being GM.

The season turned around, the Suns won 39 games—they had won only 16 the year before—and made the playoffs. Their opponent was the Los Angeles Lakers who had three eventual Hall of Famers: Elgin Baylor, Jerry West, and Wilt Chamberlain. Connie—who was 6’8″—had played against Wilt in schoolyard tournaments and had not been intimidated by the 7’1″ “Big Dipper.”

The Suns were blown out in the first game, but in the second Hawkins had 34 points and 20 rebounds against Chamberlain, and the Suns evened the series. It was “the greatest individual performance I’ve ever seen,” said Colangelo.

The Suns won the next two games in Phoenix and were up three games to one against the mighty Lakers. But they couldn’t sustain their high level of play and fell to Los Angeles in seven games.

For Connie Hawkins, it was a season of redemption. He averaged 24.6 points (sixth best in the league), made the All-Star team, and finished fifth in MVP voting. For five seasons in Phoenix, the Hawk’s dazzling over-the-rim play and sensational shots made him the most exciting player to watch in the NBA. He would go on to play two seasons with the Lakers and end his career with the Atlanta Hawks.

On Nov. 19, 1976, the Phoenix Suns named Connie to their Ring of Honor and retired his number 42 jersey. No Sun would ever wear that number again.

Connie Hawkins was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1992. He passed away on Oct. 6, 2017, at the age of 75.

One of the greatest players of all time, his mirrors the experience of many black athletes whose dreams have been crushed by a racist society. For the Hawk, at least, the dream, though delayed, eventually came true.

“I think back to when Connie and I played in that All-Star game in New Jersey, right after high school,” said Hawkins’ teammate Paul Silas. “I try and conceive what it would have been like for me, at that age, to have my college years taken away, to be scorned as a crook, to be forced to go out and face life. I couldn’t have handled it. I don’t know how Hawk kept his sanity. But he did—and now he’s proved he’s as great as they say.”