Tens of thousands of young people took to the streets of Glasgow, Scotland, Nov. 5, demanding world leaders gathered at the U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP26) take urgent action against the climate emergency. The protest, part of the weekly global “Fridays for the Future” climate strike of young people, includes thousands of local youth who defied school authorities to attend.

Meanwhile, governments are intensely negotiating a pact to keep a global temperature rise of 1.5° Celsius “within reach” to avoid ecological and societal collapse. Greenhouse gas emissions must reach net-zero by 2050, in addition to massive carbon removal, to have a chance of reaching the goal.

World leaders, scientists, environmental justice and labor activists, NGOs, and business leaders agree humanity stands at a “fork in the road.” The climate crisis is here and knows no borders. Avoiding catastrophe will take greater urgency, ambition, action, and financing than presently exists.

President Joe Biden, who apologized for the destructive climate policies of the former White House occupant, and others called for an acceleration of action during this crucial decade if the world is to “bend the curve” on emissions.

On the one hand, the conference offers reason for hope. National targets and plans mandated under the Paris Agreement now cover 90% of the global economy. Brazil and India became the latest large economies to pledge net-zero emissions, although India will not achieve the goal until 2070.

Important agreements were reached, including a pact to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030, the most lethal of greenhouse gases, and halt and reverse deforestation by 2030. The U.S. and other countries agreed to end international financing of coal, oil, and gas projects by the end of 2022. But only 46 countries, not including the U.S. and China, agreed to phase out coal.

This is despite the fact that the cost of producing energy with renewables has plummeted and is now cheaper than fossil fuels. Some 90% of new energy investments are projected to be in green technology.

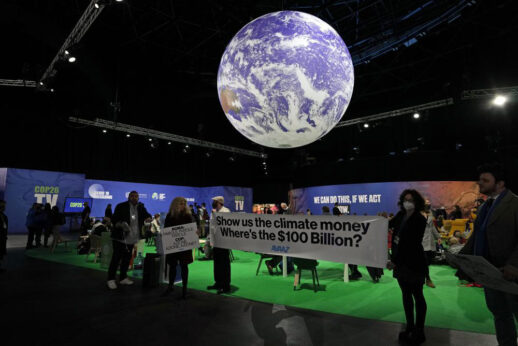

But the world has been here before and heard stark warnings and then watched pledges go unfulfilled. For example, the goal to achieve a $100 billion Green Climate Fund to aid in the transition to green energy in developing countries has so far fallen short and is two years behind schedule.

“A hundred and thirty trillion dollars worth of banks were joining in a ‘net-zero alliance’, but one which mystically allows them to continue loaning to fossil fuel companies. It’s not very hard to see why Greta Thunberg (who hasn’t been invited to talk) described the proceedings today as a ‘global north greenwash’,” wrote environmentalist Bill McKibbon in a dispatch.

So far, pledges to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that cause global warming, while significant, still will result in a 3° Celsius rise in temperatures. The key to reaching the goal of net-zero is action by the G20 countries, which emit 80% of GHG, to decarbonize their economies. The U.S., historically the world’s greatest polluter and largest emitter per person, and China, the largest total emitter today, account for 40% of the world’s emissions.

Developing countries on the front lines of the climate crisis, including island nations, expressed their anger and distrust of the wealthier countries based on a history of inaction and the “vaccine apartheid” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The world’s wealthiest countries, they said, bear responsibility for causing the climate crisis and must assist developing nations who are now dealing with the brunt of the effects.

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley bluntly warned of the “gaps” facing humanity, including incomplete plans for mitigating GHG emissions and pledges that fall short of limiting temperatures to 1.5°. The gaps in international finance and commitments to help developing countries transition to clean energy technology won’t be met by 2023. Nor will the gap in adaptation finance, which at present has only been funded at a 25% level.

“If Glasgow is to deliver on Paris, it must close these three gaps,” Mottley said. “Are we so hardened we can’t hear the cries of humanity?” Many goals, she said, were backloaded and based on technology that doesn’t yet exist.

Estimates for the cost of decarbonizing the global economy range between $100 and $ 150 trillion. Mottley insisted that wealthy capitalist countries have resources to fund the transition to clean energy and adapt to climate change, especially since they became wealthy by looting developing nations’ resources and labor. And a lot of pollution of transnational corporations has been outsourced to developing countries, like China, which is the world’s workshop.

“There is a sword that can cut this Gordian knot, and it has been wielded before. The central banks of the wealthiest countries engaged in $25 trillion of quantitative easing in the last 13 years. Nine trillion of that was in the last 18 months to fight the pandemic,” said Mottley. “Had we used that $25 trillion to purchase bonds to finance the energy transition or transition of how we eat or how we move ourselves in transport, we would now today be reaching that 1.5° limit that is so vital to us.

“One point five is what we need to survive. Two degrees is a death sentence for the people of Antigua and Barbuda, the Maldives, Dominica, Fiji, Kenya, Mozambique, and yes for the people of Samoa and Barbados. Try harder.”

The Biden administration released a detailed long-term plan to reduce emissions by 50% by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The document outlines the pathway to decarbonize the energy sector, cut energy waste, electrify end-users, including vehicles, reduce methane and other non-CO2 emissions, and scale up carbon removal by protecting and expanding natural areas, ecological systems, and agricultural practices.

“Within five years, the United States will develop a national Sustainable Ocean Plan to sustainably manage our ocean area under national jurisdiction,” announced U.S. Climate Envoy John Kerry.

The plan’s success depends on an “all-of-government and society” approach. But it also depends on the passage of the Build Back Better legislation, which boasts the most significant investments in clean energy ever. However, the legislation is minus the clean energy program gutted by Sen. Joe Manchin D-W.Va., at the behest of the fossil fuel industry and opposed by the Republican Party.

Continuing climate-centered policies also depends on Biden being re-elected in 2024 and maintaining Democratic majorities in Congress in 2022 and 2024.

International financial institutions and the private sector have a significant presence at COP26, one which fortunately goes beyond the attempted greenwashing of the fossil fuel industry, which is taking place to be sure. The transition to clean energy requires trillions in assets and the investments of a significant section of global capital; state action alone won’t be enough. Many on Wall Street realize that the climate crisis presents a risk to their existing investments and are using their political capital to protect them. Others are motivated by the profits anticipated from the transition to renewables globally. Capitalists like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos are dangling large sums to influence the course of development.

Negotiators are hammering out agreements on carbon offset markets, and investment funds are betting heavily on green energy. Biden announced the creation of a First Movers Coalition, involving large corporations and wealthy capitalists to promote low-carbon products and spur green supply chains.

Government pledges and corporate investment schemes will all be a part of the mix, but the organized force of humanity will be needed to make them happen—that’s what it will take to save the day and the planet.

The world is running out of time, and the COP26 gathering is only scratching the surface of the enormous challenges ahead. Activists and scientists have doubts the goals can be reached without breaking the resistance of the fossil fuel industry. There are also the challenges of overcoming political instability, sorting out financing issues, and finding a way to decarbonize the global economy in a way that is fair and inclusive, and leaves no country, community or worker behind.

Barbados’ Mottley was clear about the stakes involved. “Our world stands at a fork in the road, one no less significant than when the U.N. was formed in 1945. The difference is the majority of countries here didn’t exist. We want to exist 100 years from now,” she said. “If we don’t act, we will allow greed and selfishness to sow the seeds of our common destruction.”