It is enshrined in the collective consciousness of the West that the collapse of the Soviet Union was a failure of lifestyle as much as politics.

According to this view, the tedium of Soviet consumer goods was a fatal flaw in the system, grinding down morale and stoking the desires of the Russian citizen for blue jeans and other trappings of U.S.-style consumerism. You might call this the washing machine theory of history.

When President Nixon suggested to Nikita Khrushchev, in the famous “kitchen debate” at the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow, that it would be better to compete over washing machines than rockets, he was rubbing his counterpart’s nose in the superiority of U.S. products.

In her magisterial oral history of post-Soviet Russia, Second-Hand Time (2013), Svetlana Alexievich provides plenty of voices that support this particular perspective.

One of her interviewees recalls people “throwing out everything old and Soviet and replacing it with everything new and imported… Every conversation was sprinkled with words like ‘Panasonic,’ ‘Sony,’ ‘Philips’….” Yet many others are despondent, bewildered by having thrown away a noble social experiment—for what, blue jeans and a hundred types of salami?

The choice is framed as between a great country and a normal one. Normality won.

This was a country prepared to invest in the most heroic feats—a man in space—but not in everyday desires. And yet, the fact that it is somehow a truism that Soviet products were substandard ought to make one suspicious. Indeed, it may be a consequence of how assured we are in our opinions of “Soviet design” that the subject has been so little studied.

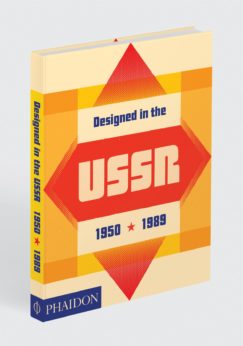

Designed in the USSR: 1950-1989, just published by Phaidon, is one of the few books on the topic. While not a revisionist history offering up a parade of unsung masterpieces, it does, however, assemble a landscape of everyday life in the USSR, and that is a valuable step towards understanding a period that is receding fast.

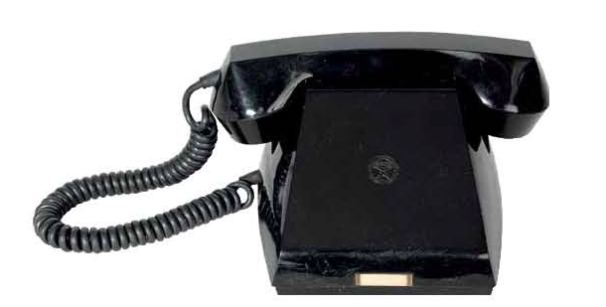

Here are the vacuum cleaners, table lamps, radios, cigarette packets, film posters, coffee tins, and toys—the minutiae of a lost civilization.

It is true that communism as manifested in the USSR—centralized, bureaucratic, and unconducive to competition—was not fertile ground for a rich material culture. It is also true that many Soviet products were copies of Western models. Notoriously, the Vyatka scooter was an imitation Vespa down to the very logo font.

This parallel world of ersatz knock-offs was encouraged by party dignitaries returning from foreign trips with souvenirs that they would drop off at the konstruktorskoe buro (design department) of the relevant factory so that they could be reverse-engineered.

The All-Union Scientific Research Institute for Technical Aesthetics (VNIITE) did its best to foment a dynamic design culture, spearheaded by the journal Technical Aesthetics, but they were working against the grain of an economic system that was not geared up for stylistic variety. With Five Year Plans and production targets, factory directors were loath to retool the production line just because VNIITE had a better design up its sleeve.

One might argue that the system had its virtues. After all, Western materialism depends on a culture of disposability, bewildering choice, rapid obsolescence, and keeping up with the Joneses.

By comparison, the Soviet system was admirably sustainable. Avos’ki, fishnet shopping bags, are vastly preferable to plastic ones, as are collapsible cups for use in drinking fountains compared to the insanity of plastic bottles.

And those Space Age vacuum cleaners were nothing if not durable. But, just as invidious comparison makes Western consumers feel inadequate, so it gnawed away at Russians with one eye on life across the Iron Curtain. The domestic world of Homo sovieticus, as Alexievich calls pre-Yeltsin Russians, is laid out in the book’s pages, at least in part. It is a collection worthy of closer scrutiny, one that may be as curious to Russians born after 1991 as it is to those in the West.

When these items went on display at the Moscow Design Museum in 2012, the exhibition received 150,000 visitors. That is a sizeable audience for a group of objects that would have been utterly mundane only a generation ago.

The question is, what was the appeal? Was it fascination for a time that now feels impossibly distant or nostalgia for a country that once placed less stock in material things?

Extracted from Justin McGuirk’s foreword to Designed in the USSR: 1950-1989, published by Phaidon. Courtesy Morning Star.