SAN ANTONIO — Emma Tenayuca was born Dec. 21, 1916, to a large family in San Antonio. Her grandfather, Francisco Zepeda, helped her read newspapers as a young girl and often took her to San Antonio’s Plaza del Zacate, a gathering spot where community leaders shared news and talked about politics. The discussions instilled in her a lifelong passion for learning and social justice. By 15, she was a gifted, well-read high school student, who could debate the issues of day in English and Spanish.

At age 16 she began to organize workers for the national Workers Alliance and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. By 1934 she was 18-years-old, and was arrested for her leadership role in the organization of Mexican women in the Finck Cigar Strike. It was the first time in San Antonio’s labor history when a group of skilled minority women workers challenged the owner of a manufacturing plant on pay violations, unfair production quotas and unsanitary working conditions.

Four years later, in 1937, she joined the Communist Party USA and soon became its Texas chairperson in San Antonio. It was likely the time when she was given the nickname “La Pasionaria” [the passion flower] after the equally passionate contemporary Dolores Ibárruri, Spanish Republican heroine of the Spanish Civil War and communist political activist of Basque origin.

On January 31, 1938, through her participation with the Workers’ Alliance, she organized and successfully helped lead an estimated 12,000 pecan shellers in a four-month strike in response to poor working conditions and the bosses’ cutting shellers’ pay from five to three-cents an hour.

Harsh conditions included a lack of toilets and wash bowls, poor lighting and poor ventilation. The poor ventilation, together with the industry’s indoor dust, contributed to the city’s tuberculosis rate which was disproportionate to the national average. A 54-hour work week brought in approximately two dollars for pecan shellers who were mostly women and either Mexican or Mexican-American.

At that time there was a 250-mile radius around San Antonio which was the largest pecan-producing region in the country. The region yielded 50 percent of the nation’s pecan harvest and was San Antonio’s largest industry. With the representation of International Pecan Shellers Union No. 172 and additional organizational work of the Workers’ Alliance – in which Socialist and Communist workers participated — Tenayuca and other labor organizers coordinated the picketing of the city’s 400 pecan shelling factories. Pickets were frequently interrupted by police intervention and mass arrests.

The bosses’ reaction was fierce: in a single week alone, nearly 300 demonstrators were imprisoned in a county jail that was designed for a maximum of 60 inmates. However, then-Gov. James Allred pressed the Texas Industrial Commission to investigate civil rights violations. The commission found police actions unjustified.

Both sides eventually agreed to arbitration, and the workers won a wage increase of 7-8 cents. “What started out as an organization for equal wages turned into a mass movement against starvation, for civil rights, for a minimum-wage law,” Tenayuca recalled in 1987. The strike also marked “the first successful sally in what became the Mexican-American social justice movement,” notes University of Texas historian Don Carleton.

By August 1939, Tenayuca had been elected chair person of the Communist Party USA in Texas and was among others scheduled to speak at a gathering of her party at San Antonio’s Municipal Auditorium.

About 200 were in attendance, demanding union rights, a minimum wage, Social Security, and racial equality — goals that a local newspaper derided as a “socialist plot.” Ku Klux Klan members and several thousand other reactionaries rioted outside, and Tenayuca and the others were placed under temporary, protective custody.

This event was followed by a crackdown on Communists in the San Antonio workforce in which the political-economic machine of this city fired and denied employment to Communist workers and sympathizers.

Tenayuca was unable to find work and was forced to leave San Antonio for California. After obtaining a degree there, she returned to San Antonio to serve her community as a school teacher. She earned a master’s degree and taught migrant workers’ children how to read in the Harlandale Independent School District until retiring in 1982.

Beginning in the 1970s, Tenayuca’s life became a topic of intense study within the Chicano Movement, and her achievements as a pioneering female civil rights leader were recognized by scholarly organizations like the National Association for Chicano and Chicana Studies and Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social (Women Active in Letters and Social Change). In 1981, the Institute of Texan Cultures made Tenayuca part of its exhibit of outstanding Texas women.

Emma Tenayuca was honored with a Texas historic marker at San Antonio’s Milam Park in 2011. “We’re very proud of the courage she had and that there is now recognition of the personal stands she took at such a young age,” said Sharyll Teneyuca, a San Antonio attorney and niece of the labor leader. (She spells her surname differently than her aunt’s.) “She was 21 when she led the pecan-shellers strike, and she was organizing long before that.”

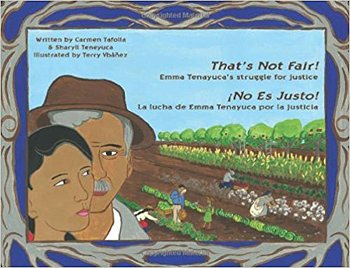

Emma Tenayuca’s life has been the subject of murals by Theresa A. Ybáñez and others. Sharyll Teneyuca and San Antonio writer Carmen Tafolla wrote a children’s book, “That’s Not Fair: Emma Tenayuca’s Struggle for Justice/ No Es Justo: La Lucha de Emma Tenayuca por la Justicia,” in 2008. The book is currently available in a hardcover and a Kindle edition. Carmen Tafolla was San Antonio’s first Poet Laureate and the 2015 Poet Laureate of Texas.

Emma Tenayuca’s life has been the subject of murals by Theresa A. Ybáñez and others. Sharyll Teneyuca and San Antonio writer Carmen Tafolla wrote a children’s book, “That’s Not Fair: Emma Tenayuca’s Struggle for Justice/ No Es Justo: La Lucha de Emma Tenayuca por la Justicia,” in 2008. The book is currently available in a hardcover and a Kindle edition. Carmen Tafolla was San Antonio’s first Poet Laureate and the 2015 Poet Laureate of Texas.

Emma Tenayuca died July 23, 1999 in San Antonio, Texas.

From Wikipedia and other sources. Barbara Russum contributed to this article.

Updated October 6, 2017.