ZACATECAS, Mexico—This colonial city, founded in 1546 after the discovery of one of the world’s richest silver veins, is the capital of the State of Zacatecas in North-Central Mexico. The state is Mexico’s eighth largest in area (larger than West Virginia, smaller than South Carolina), with a population of over 1.5 million. It is considered the northernmost of the colonial-era towns, gateway to the more sparsely settled northern tier of Mexican states. It is surrounded by Durango and Coahuila to its north, Nuevo León and San Luis Potosí to the east, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, and Guanajuato to the south, and Nayarit to the west. The irregularly shaped mountainous state has the outline of an absent-minded professor walking distractedly—though a native-born Zacatecano sees it as an eagle.

The city’s formal name is Nuestra Señora de los Zacatecas, meaning “Our Lady of the Zacatecas (Indians).” The baroque cathedral is an impressive edifice right in the center of town next to government buildings and a block away from the French-inspired Porfirio Díaz-era theater. Owing to the excellent preservation of its public buildings of the colonial period made of cantera, a pinkish stone, in 1993 UNESCO named the historic center of Zacatecas as a World Heritage Site, a cherished designation that contributes to civic pride and attracts visitors.

The city has a well developed tourist industry, with brochures highlighting local gastronomy, walking tours, museums, historical and architectural sites, and the silver and mining industries. I especially enjoyed my dinner at Acrópolis, with its varied menu and exuberant displays of artwork covering every available surface. Its hotels range from modest to elegant. One of the most amazing feats of historical reclamation I have ever seen is the old Plaza de Toros dating from 1866. It went out of use in 1975, and later the modern Quinta Real hotel was constructed surrounding and enclosing it, preserving the ring as its central open-air function space. The classy hotel restaurant is on several levels corresponding to the raked rows of seating at the bullfights.

The high price of silver

El Pregonero (The Town Crier), an eight-page monthly publication of the Archivo Histórico del Estado de Zacatecas, consists mostly of documents found in the Archive that might pique readers’ curiosity, alongside photos of old Zacatecas and modern art by local artists. The November issue carried an item from 1727 which reprinted portions of the last will and testament of a certain wealthy man, Don Domingo Francisco de Calera, an immigrant from Spain who had established a number of haciendas in the region. The excerpt detailed his manumission of two of his slaves, Francisco José and Domingo de los Santos, granting them land and animals “for the loyalty and love with which they have served me.”

The names Francisco and Domingo suggest that these two men were Indigenous people whom the Don raised and renamed after himself. In any case, it was almost exclusively Indigenous people who were enslaved in Mexico’s colonial era, a policy with political, economic, and religious underpinning, justified by the cynical theory that the native Indians were not exactly human beings anyway, but that either way, Christianization would ultimately be for the good of their eternal souls whatever happened to them on (or beneath) Earth. As a result of disease, overwork, and starvation in that time, today Zacatecas has the smallest percentage of fully Indigenous population in Mexico, only 0.3 percent (not counting everyone who is culturally European but may have some Native DNA).

Zacatecas is silver. Much of its history even up to the present is related to mineral production, especially silver. The first century-long boom was from the Conquest to the mid-1600s. In another boom time in the early 18th century, Zacatecas mines produced a fifth of the world’s silver. New townships were established around the mines, and the wealth derived from them allowed for the erection of magnificent churches and private mansions. The state became one of the most important treasure houses of New Spain, and by extension the mother country Spain. The industry experienced a slump during the Mexican Independence wars, in part because Independence abolished slavery, but the rich mineral veins were still there to exploit, and over time silver once again rose to 60 percent of the state’s export revenue.

Zacatecas today accounts for 21 percent of Mexico’s gold production and 53.2 percent of its silver. The state has two of the largest silver mines in the world, making Mexico the world’s largest producer of silver, with 17 percent of global output.

One of the city’s major tourist magnets is the Mina El Edén. Whoever named this mine El Edén must have had an acute sense of irony. It was no Eden by any definition for the many thousands of Indigenous slaves, and later paid employees who were little more than slaves, who worked to pry the silver out of the bowels of the Earth. Irony obviously runs deep in Zacatecas: The state’s Latin motto is “Labor vincit omnia”—Work conquers all, including its people.

El Edén, which flourished as an active mine from 1586 all the way up to 1960, still has ample silver reserves, but it is located right in the middle of the city. By 1960 the city had grown so large that continued mining operations would have been too dangerous. Left to fill in with water, it was drained and reopened in 1975 as an efficient, well managed tourist and educational site. A cute little train transports visitors 500 meters inside the mountain. At that starting point of the guided tour we are 280 meters underground, and we walk through the well lit tunnels to 350 meters down.

The tour takes us as far down as the fourth level. From there we could peer down into the waters at the lower levels, but those levels are subject to flooding, and normally not open to the public. We pass any number of tunnels going off in every direction, but those are not on the tour. One could imagine getting easily lost if left there alone.

The tour we joined was mostly for high-school aged youngsters, and I was happy to see them receive this education. No doubt many of their ancestors worked and perished in these mines. Our guide clearly had much of her information semi-memorized, but she comfortably responded to questions. She warned us all to keep our helmets on tight, for indeed the tunnels were often not much higher than an adult person, and rocks are known to fall. I have friends who are well over six feet tall and I know they would have felt very uncomfortable stooping all the way through this underground adventure. As we walked along the path, we could hear helmets scraping alongside the rocky tunnel ceiling.

El Edén is a powerful tribute to the ingenuity of the human mind, to conceive of a project so vast and so productive, that yielded enormous wealth for a few individuals and for the Spanish Empire, and that placed so many fellow human beings in a status barely superior to that of draft animals. Edén was not unique, of course: Labor conditions in the mining industry have historically always been oppressive.

The owner of the mine, our guide told us, claimed he was the only person authorized to call himself a “minero”—a miner. Everybody else in this highly articulated system had another title: porters, carriers, water boys, smelters, etc. One later owner of this mine, in the latter half of the 18th century, was Don Manuel de Retegui, of Basque origin, who built for himself a resplendent palace across from the Cathedral, called Palacio de la Mala Noche, so named after one of his other mines. Today this handsome building serves as the Superior Court of Justice for the State of Zacatecas.

All through the colonial period, slave workers were never paid in specie, but only in beans, corn, rice, molasses, and lentils, just enough to keep them barely alive. After Independence and the abolition of slavery, workers were paid with money.

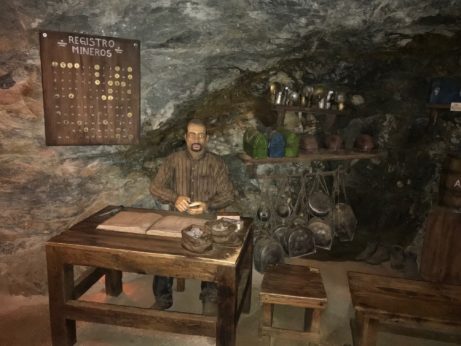

At our stopping points along the route, the guide paused before a dozen or more tableaux showing different phases of the mining process. Only men worked in the mines. You would never see men in their forties or fifties, however. Few workers survived past thirty, losing their lives to accidents, cave-ins, falls, respiratory disease, and fights with one another.

Indians asked for protection from the Niño de Atocha, a representation of the Baby Jesus named for a town in Spain, which is now located in a shrine in Fresnillo, Zacatecas. On one wall of the mine, alongside what was once an altar, they hung “retablos” or ex-votos, painted prayers for healing after an accident or injury. In an environment where salvation came from no other source, religion had its place—”the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions,” as Marx would poetically say a couple of centuries later.

In the earliest times, only a rag around the head or an insubstantial straw hat protected workers from falling rocks. The miners devised a primitive and sometimes effective “alarm system” against falling rocks. Up high in the crevices between veins they constructed wooden platforms called “chismosos” (gossipers). When the wood started screeching, that signified weight on it from falling rocks, meaning the miners had to run away.

One of the tableaux showed steep stairs with risers a foot high and a foothold of only four inches or so. Workers had to climb these narrow stairs with a basket of ore on their backs. It was common for someone to lose his balance and fall backward, toppling several others behind him in domino fashion.

Every worker had a “ficha,” a token with his name or number left at the mine door indicating they were working, which he picked up at the end of his shift. If the ficha was still there, that meant he had died in the mine that day. On average, one to four men died every day in the mine: Life was cheap, an insignificant mess of beans and corn.

Children as young as eight years old worked as “achichincles,” the Nahuatl word for a water carrier. Mules were also brought in to wheel out cartloads of ore. To Don Manuel de Retegui, the mules were undoubtedly worth more than the children.

Over time, as illustrated by the tableaux, the technology of mining evolved. Pickaxes were replaced by pneumatic drills and dynamite. Helmets and lights came in to protect workers a little more. In the 1930s, they started using canaries to determine oxygen levels in the tunnels.

Since the re-opening of Edén as a historical and tourist site, the mine has also included a fancy nightclub and discotheque in a huge carved-out space with a domed ceiling. A popular gathering spot for drinks and dancing, the club is also reached by the little train that leads from the street level.

And what’s a decent mine without a good ghost story? This one also serves as a morality tale. Roque was a very greedy miner who found a nice nugget of gold and announced to his fellow workers, “This rock is mine.” These were his last words: A cave-in occurred and he was buried in the rubble. Afterward, Indians removed every rock, but never found Roque or his gold. Now any time you’re in the mine and feel a tap on your shoulder or someone trying to grab your legs or feet…it’s Roque!

Heroic city and magical town

At the end of the tour, visitors can either return to the starting point with the guide or take an elevator back to the surface, placing you near the city’s teleférico, a modern aerial tramway that spans the central city to the next mountaintop, La Bufa, one of the most historic attractions in Zacatecas.

A century after the war of Independence, Zacatecas was again a battleground during the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1917. One of the most decisive battles took place here: the “Toma de Zacatecas” (Taking of Zacatecas). This battle pitted the troops of Francisco “Pancho” Villa against those of Victoriano Huerta, resulting in the deaths of 7,000 soldiers and the wounding of 5,000 more; civilian casualties went unrecorded. Zacatecas was named a “Heróica Ciudad” (Heroic City).

Atop the mountain are statues of mounted revolutionary leaders Pancho Villa, Felipe Angeles, and Pánfilo Natera, an informative Museum of the Revolution, a small church whose original construction goes back to 1548, a mausoleum for distinguished personages in local history, some eateries, and many outlook points over the sprawling city. A park guide dressed in the outfit of a revolutionary soldier, complete with theatrical black mustachios that he kept adjusting to keep in place, recounted the story of the battle to an amused school group.

In and around Zacatecas are other mines that can be visited, as well as a proliferation of shops selling silver items and other local products: A couple that caught my attention (but not my pesos) were jars of gel made of peyote recommended for relieving body aches and pains, and a marihuana pomade.

Jerez de García Salinas, or simply Jerez, is one of the state’s five “pueblos mágicos” (magical towns), sitting an easy 45-minute drive from the state capital. Unlike Zacatecas, Jerez is located on a flat plain at a lower altitude, so it is markedly milder in climate. Jerez has a charming central jardín (garden) with splashing fountains, where, on the Sunday that I visited, local brass and drum bands gathered to entertain passersby. It has a good-sized church, a more than century-old theater, and a well maintained commercial zone, as well as another even larger park in the central area and an open-air tiangui, a farmer’s market cum swap meet. It is the very picture postcard image of a typical Mexican town, with colorfully dressed Huichol women and children selling their handicrafts.

A couple of blocks from the church, a visitor will find at Calle de la Parroquia, 33, the comfortable 19th-century bourgeois home and now museum dedicated to the poet Ramón López Velarde (1888-1921), whose most famous poem, “La Suave Patria” (The Gentle Country), published three weeks before his death of bronchial disease, is still studied by Mexico’s schoolchildren. Its language is somewhat antiquarian and overblown, with broad religious reference, not reflective at all of the modernist currents that started appearing in the post-World War I period, nor indeed of the spirit of the recent Mexican Revolution. Nevertheless, Don Ramón’s florid expressivity attracted the notice of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, whose signed appreciation of his Mexican forerunner is one of the exhibits in the museum. The official state Instituto Zacatecano de Cultura is named for Ramón López Velarde.

Zacatecas has sent thousands of emigrants northward to the U.S. Some 600,000 natives Zacatecans now live in the U.S.: That equates to 40 percent of the state’s current population. Jerez is a favorite retirement place for Mexicans returning home for their “tercera edad”—the last third of their lives.

Tourist articles tend to emphasize the positive, but of course not all is “Edenic” in Zacatecas, and never was! If it were, not so many natives of the state would have left for greener pastures either in other states, such as nearby Aguascalientes, with its automotive factories, or the United States.

The first day I was there it rained steadily, but suddenly mid-morning the water went off in our house, just as my shower was beginning to warm up and my hair was full of shampoo. My host blamed it on water rationing because the mining industry—still the single largest factor in the state economy—uses a lot of water, and also water is diverted to the local Corona brewery in town. A few days later the true reason emerged: The guy who is employed to turn on the district’s water valves every day came down with pneumonia, so no water for a few hours.

I did not visit the other mines, but I trust conditions there are nothing like they were in El Edén. The governor of Zacatecas belongs to PRI, not Morena, so it is possible that the state may be slow to line up with the new President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s vision for the future of Mexico. Vamos a ver: We shall see.