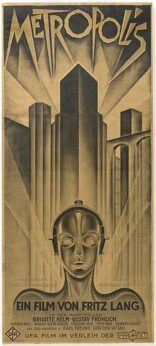

One hundred years ago, in 1925, the serialized version of the novel Metropolis was published in the German magazine Illustriertes Blatt with the intention of it being adapted into a film. In 1927, it hit the big screen and eventually came to be seen as pioneering science-fiction cinema, being among the first feature-length films of the genre.

The epic silent movie, with its larger-than-life sets, explored themes of working-class struggle, exploitation, industrial revolution, aggressive technological advancement, and the growing wealth gap between the rich and the poor with vigor. And while it made amazing cinematic somersaults with the issues it touched upon, it ultimately fumbled the landing with an oversimplified message of class collaboration and talk of some great class “mediator.”

The epic silent movie, with its larger-than-life sets, explored themes of working-class struggle, exploitation, industrial revolution, aggressive technological advancement, and the growing wealth gap between the rich and the poor with vigor. And while it made amazing cinematic somersaults with the issues it touched upon, it ultimately fumbled the landing with an oversimplified message of class collaboration and talk of some great class “mediator.”

Nonetheless, it is a fascinating dystopian science fiction film that is still relevant today. Metropolis envisioned the world of 2026, and as we approach that year in the calendar, unfortunately, there are many parallels between the speculations of 1927 and the reality we inhabit now.

Directed by Fritz Lang and written by Thea von Harbou (who also wrote the novel) in collaboration with Lang, Metropolis stars Gustav Fröhlich, Alfred Abel, Rudolf Klein-Rogge, and Brigitte Helm. Set in a futuristic urban dystopia, Metropolis follows Freder, the wealthy son of the City Master, who represents the wealthy, and Maria, a saint-like figure to the workers. Wealthy industrialists, business people, and their top employees reign over the city of Metropolis and enjoy lives of luxury and indulgence in colossal skyscrapers. Far below them, underground-dwelling workers toil to operate the great machines that power the city.

The workers’ sole purpose is to work long shifts tied to the advanced machinery that keeps the city going. Freder is knocked out of his ignorance-is-bliss existence when he witnesses Maria being thrown out of the wealthy gardens after she brings the workers’ children inside. While seeking her out, Freder witnesses multiple workers being killed on the job due to a machine malfunction. This sets him on a mission to uncover the plight of the workers and figure out a way to help them. What follows is a story filled with robots, false prophets, a violent uprising, and somehow the conclusion that workers shouldn’t replace the ruling elite but work with them for a better society.

The film’s message is encompassed in the final intertitle: “The Mediator Between the Head and the Hands Must Be the Heart.” It’s a clear nod to the corporatist philosophy which sees society as a single body—the industrialists and business people are the “head,” the workers are the “hands,” and there needs to be a “heart” to bring them together to create a more balanced society. Class struggle? No need.

The film includes a variety of themes and sentiments, not all of which fit together cohesively; some are downright contradictory with one another. When it first premiered, the movie was actually accused of pushing communist messaging. Later, with the rise of Nazi Germany, analysts of the film would veer toward a look at its possible fascist and authoritarian leanings. Interestingly enough, all of these sentiments have bits of truth in them, and lessons can be learned from why these various viewpoints or sympathies intermingled when looking at the plight of workers during that time.

First, however, we have to explore Metropolis in the historical context in which it exists to understand what shaped its final form.

The Weimar period

Germany found itself on the losing end of the First Great War (World War I), which lasted from 1914 to 1918, and that defeat’s impact was felt far beyond the battlefield, with economic and psychological catastrophe falling heavily on the workers of the country. Under the strain of such tensions, the German Revolution of 1918 erupted, also known as the November Revolution. Workers and soldiers came together to do away with the then-ruling Kaiser Wilhelm II, ending the Monarchy of Germany, which had existed since 1871.

Partially inspired by the 1917 Bolshevik-led revolution in Russia, with leaders such as Vladimir Lenin, many in Germany hoped for a government led by working people and not the wealthy aristocrats. Among those who’d overthrown the empire and were now tasked with deciding a new road forward for Germany, there emerged serious disagreement over just how far the workers’ revolution would go.

In 1918, the country was declared a republic, with the leader of the popular Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Friedrich Ebert, becoming leader. Yet, the centrist SPD had a recent history of colluding with far-right anti-revolutionary forces as a means of keeping so-called peace and order. Their idea was that the Bolshevik-led Russian Revolution was too violent and that a transfer of power could be carried out differently—to the detriment of the workers.

Divisions had already begun, with split-offs from the SPD by members who questioned the party’s support of Germany’s involvement in WWI. Influential forces emerged, such as the Spartacus League, which would later help form the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). From 1918 through 1919, there was a constant push and pull between these forces, with Ebert’s group wanting to dilute the power of workers councils and worker-led government and those of the Spartacus League, with leaders such as Rosa Luxemburg, who aimed for a Soviet republic that would include all of Germany.

And while there were attempts at coups by the far-right to try and re-establish dominance, it was ultimately the fighting among the leadership, and Ebert’s group’s refusal to truly lean into a worker-led government, that would be the greatest hindrance to this revolution. By 1919, many workers felt that the revolution had not achieved its goals, such as nationalization of key industries, recognition of the workers’ and soldiers’ councils, and establishing a Soviet republic. This clash of forces resulted in much bloodshed, including the murders of Luxemburg and her colleague, socialist leader Karl Liebknecht, at the hands of right-wing paramilitaries dispatched by the SPD.

In 1919, there was a National Assembly election—in which women were allowed to vote for the first time—in the city of Weimar. There, the Weimar Constitution was created, making Germany officially a parliamentary republic. Ebert was made the first president of Germany and served in office until he died in 1925. He was followed by the nationalist right political leader, Paul von Hindenburg, who won the presidential election, showcasing the continued political divisions in the country. This also happened during what is known as the “Golden Twenties” of Germany from 1924 to 1929 which saw some economic growth and recovery after years of being ravaged by the aftermath of WWI and before the collapse of the Great Depression.

Suffice it to say, Metropolis was made at a time when Germany was torn by class struggle and a constant battle of ideas. The country’s people were at first disillusioned with capitalism, leaning towards the ideals of socialism and democracy, but they also still contended with far-right forces wanting a return to authoritarian rule, and workers overall wanted stability.

The film showcases many of these elements, in all their conflicting and at times contradictory glory.

Class conflict, fascism, and Marxism

At the heart of the Metropolis story is the question of how to solve class conflict. The workers in the film live a miserable existence, struggling to survive underground and working 14-hour shifts, with little joy to be found. Their labor is the main source of fuel for the lavish city, with the ruling wealthy able to indulge in entertainment and leisure, along with Garden of Eden-like parks where the women are made readily available to the men in charge.

Director Lang makes it clear that despite the surface-level prosperity of the city, the fact that workers live the way they do—along with experiencing danger on the job due to a total lack of safety precautions when working with advanced technology—that this is no utopia.

Maria, the prophetic symbol of the working people, serves as a catalyst for the film’s plot. It is her peaceful act of defiance in bringing the workers’ children to one of the wealthy gardens to declare to the children, “These are your brothers,” before being escorted out, that sparks intrigue in spoiled-rich Freder.

Maria gives underground sermons to the workers in which she recites Biblical tales with a class-conscious spin on them, preaching that there will be an end to their suffering and that all hope is not lost. The workers look to her as a beacon of hope and positivity.

It is also Maria who first utters the main message of the film, that the coming of a “great mediator” will improve society for the better. Someone who will be able to connect the “head”—the wealthy—and the “hands”—the working people. She and Freder come to the conclusion that he is, indeed, the great mediator who’s needed.

Freder’s father, the City Master, employs a mad scientist with an axe to grind who builds a robot that looks like Maria that will be used to soil her reputation among the workers. But the scientist, in wanting to destroy Metropolis due to lost love, has Maria’s evil robot clone advise the workers to violently rise up instead, destroy the machines, and trigger the fall of Metropolis.

And just like the era in which the film was made, a lot is going on in Metropolis when it comes to its politics.

There’s a clear understanding in the film that worker exploitation is wrong. As the industrial revolution progresses, the message goes, the gains can’t come at the cost of the workers’ lives. There’s a scene in the film that makes this clear, where Freder, in witnessing the workers being killed and injured on the job, envisions the machines as ancient temples and the workers being offered as a sacrifice at their altars.

In acknowledging the class conflict and the need for change, one could argue that there are some Marxist undertones there—especially as the workers rise up and lay waste to the city simply by refusing to work and damaging the machines. As stated in The Communist Manifesto by political theorist, economist, and journalist Karl Marx, when the ruling wealthy create a system in which the workers are exploited and driven to the brink of despair, “the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all…its own grave-diggers.”

Yet, Metropolis seems to classify the uprising of the workers as destructive and detrimental to both the city and the workers themselves. When they and the false prophet robot clone Maria go to destroy a factory, they are told by one of their fellow workers that by crippling the great Heart Machine, they will also flood the underground, putting their own homes in danger. This doesn’t deter the workers, however, who proceed to destroy the machine, thus leading to a great flood in their neighborhoods that endangers all of their children.

It is Freder and the real Maria who race down to save the children, while the workers are so consumed by their push to overthrow the wealthy that they’re not even thinking of the impact on themselves and their loved ones.

Given what we know about the period in Germany from the November Revolution to the creation of the Weimar Constitution, one could argue that the filmmakers did not agree with the perceived violent uprisings that occurred. They incorrectly place blame for the bloodshed that occurred at the feet of the workers rather than at those of the reactionary forces who chose to employ violence against the workers. More often than not, it was the far-right and ruling powers who first turned to violence.

Ultimately, when Maria’s evil robot clone is burned at the stake by the workers who feel she has led them astray, it is revealed that the children have been saved by Freder and the real Maria. When Freder’s father, who turned against the scientist after seeing the city falling into ruin, comes to the city square where everyone is gathered, Freder facilitates the shaking of hands between the workers’ leader and his father. Thus, he assumed his role as the great mediator.

With the idea that there would be some charismatic leader who’d appear to solve the people’s problems, it is no wonder that Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels was reportedly impressed with the film and that Adolf Hitler said he wanted Lang to make Nazi films after watching the movie.

That’s because Metropolis does have an air of wanting an authoritarian figure to come and set things “right.” The workers, although exploited, are shown as incapable of properly leading society, while the wealthy elite are shown to be too consumed with their material pleasures. The film’s shaping of Freder into an almost Christ-like figure lays the foundation for a cult-of-personality sentiment—one that Hitler fully utilized.

The conflicting sentiments at work in the film had their real-world parallels, too, as illustrated by the different paths taken by co-writers Thea von Harbou and Lang during the rise of Nazi Germany. Not agreeing with the new fascist regime, Lang fled the country, ultimately landing in the United States, where he continued making films with socially-conscious and anti-Nazi messaging. Harbou, by contrast, joined the Nazi Party and produced dozens of films for the Third Reich.

The battle of ideas was baked into the film from its conception, and as we look back on this classic work of art nearly 100 years later and approach the very year it envisions, we can continue to unpack its lessons.

The working-class struggle now and in 2026

The wealth gap is widening between the rich and everyone else the world over. We have seen many social gains made in recent decades, but there have also been considerable setbacks. At the time of this writing, the world is celebrating 80 years since the fall of fascism, which came in 1945 with the defeat of Hitler and Nazi Germany. Yet, we have also witnessed a rise in far-right leaders and ideals that threaten much of the social progress made not only in the United States but around the world.

Environmental, social, and economic crises are at the forefront of the minds of many as working people find themselves faced with the reality that their wages are not keeping up with the growing cost of living. Instead of addressing what is at the heart of these problems—the greed and exploitation of capitalism—there are those in positions of power who wish to distract and scapegoat. While there may not be underground towns of workers at the moment, there is definitely a sense that true luxury and leisure are reserved for the wealthy, as working people are forced to continue laboring well past retirement age.

Metropolis presents a number of themes that are relevant to our current struggles. The first, and perhaps most important one, is that working-class labor helps power society and that workers can’t be pushed to the brink of destruction and be expected to continue on. Metropolis in 2026 is considered dystopian for that very reason, because a truly prosperous society is not one where the majority of the population is subjected to such hardship.

The United States and other countries can’t claim to be “great” when so many live in poverty.

Another lesson to take from Metropolis is the realization that the notion some messiah-like figure, such as Freder, will come to rectify everything is nothing but a fantasy. Germany learned this the hard way with Hitler, and one could argue that those in the U.S. who support the supposed “law and order” President Donald Trump—who claimed he would drain the political swamp—are learning that now.

Metropolis is essential viewing, not only for the cinematic feats it achieved onscreen but because of the continued discussion of liberation and true progress that it evokes. By looking at the themes it explores and the time in which it was created, we can take much to heart for our own road forward towards possible prosperity or disaster. May the Metropolis year 2026 stay on the silver screen and not become our own reality.