History was made at New York City’s world-famous Metropolitan Opera when it opened the season on September 27 with its first work written by a Black composer, jazz musician, and well-known scorer of many Spike Lee films, Terence Blanchard (b. 1962). The libretto by Kasi Lemmons (b. 1961) to Fire Shut Up in My Bones is based on the best-selling memoir by Charles Blow (b. 1970), a New York Times columnist, relating his difficult Louisiana childhood as a sensitive boy in a tough, macho world. Every character in the opera is Black, and all the performers in the large cast are also Black.

Wait a minute, a reader might think. What about Porgy and Bess? Yes, an almost all-Black cast, but the composer and librettist, George and Ira Gershwin, were both white, and DuBose Heyward, author of the 1925 book Porgy, was also. That show premiered on Broadway in 1935 and has since found its way into many opera houses, offering generations of Black performers sophisticated and dignified roles granting them access to operatic stages.

There are Black characters in a number of operas, and since Marian Anderson became the first Black singer in a featured role at the Met in 1955 (Ulrica in Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera), doors have opened for Black singers increasingly on a race-blind basis. The days of white performers portraying roles like Verdi’s Moor Otello in blackface are over. Black composers who have written operas include Joseph Bologne, William Grant Still, Scott Joplin, H. Lawrence Freeman, James P. Johnson, Shirley Graham Du Bois, Anthony Davis, Leroy Jenkins, Duke Ellington, and Anthony Braxton.

The Metropolitan Opera Guild publishes the premier magazine Opera News, which carried a cover story on Blanchard and the new opera in September. “I have mixed emotions about it,” Blanchard responded when asked about Porgy and Bess. “I do think it’s a great opera, and I do think at the time it was written, it was revolutionary because it allowed a huge cast [of African-Americans] to work in the field of opera.… For me to be the first African-American to have a piece done at the Met is a huge honor. But at the same time, I keep thinking that I know, good and well, I’m not the first one to have been qualified.” Other Black composers were routinely rejected not only at the Met but almost everywhere throughout the opera producing community.

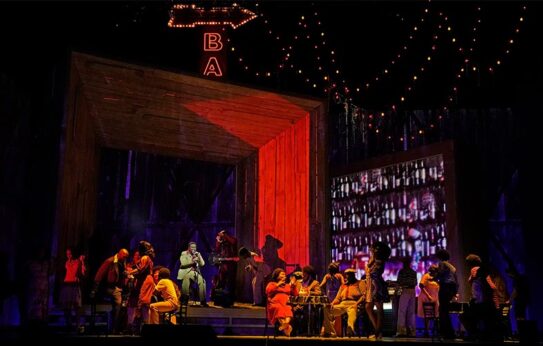

The just over three-hour-long, with one intermission, Fire Shut Up in My Bones (seen on HD live transmission, hosted by world-renowned singer Audra McDonald on Oct. 23, the last of eight performances this season) was originally commissioned by Opera Theatre of St. Louis (OTSL), co-commissioned by Jazz St. Louis, premiering in 2019. The current staging, expanding the cast from 12 to 36 performers, is a coproduction of the Metropolitan Opera, LA Opera, and Lyric Opera of Chicago, the latter of which has programmed the work for March 24-April 8, 2022, with many of the same performers.

It is not Blanchard’s first opera, however. That was Champion, also premiering at OTSL, in 2013, and since staged elsewhere. People’s World caught up with it in San Francisco in 2016. That work is the story of Emile Griffith, a gay boxer who fought Benny “Kid” Paret and accidentally killed him.

Both of Blanchard’s operas, curiously, have taken Black gay men as their subjects. Although in Fire the boy’s youthful “sweetness” and “baby” moniker hint early on at his being a pre-gay kid, his emerging sexuality—after a brutal childhood incident of sexual abuse by a relative—evolves gradually at a high emotional and psychological price. It is toward young people at that stage that the “It Gets Better” campaign was aimed several years ago, helping kids to understand that life will improve once they are older, free of home, church, school teasing, and shaming. In the Opera News interview, Blanchard relates that he could relate to childhood bullying because when he would take his horn out for music lessons every week he was also ragged on for being “different.”

In the opera, one of the artists’ targets is the Church, which presumes to heal all a person’s ills with a simple act of baptismal immersion, but which in reality only allows the “sinner” to go on as usual, knowing that God loves them and will wash their pain away. A similar theme emerges in Spinner’s (Charles’s father’s) R&B song, where Chauncey Packer sings, “The Lord love the sinner in me.”

The title of the opera (and the sourcebook) derives from the prophet Jeremiah 20:9: “But his word was in mine heart as a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I was weary with forbearing, and I could not stay.” Translation: There was a pent-up feeling inside me that was threatening to destroy me from the inside unless I let it out—which is probably about as good a way as any to express the need to “come out” or release oneself into liberation.

Char’es-Baby is the youngest of five boys in a broken family—the father is a repeat philanderer whom the mother, Billie, eventually kicks out. The mother, Billie (Latonia Moore), is the main economic support, working long hours on an assembly line in an alienating chicken processing factory, which is featured in a tragi-comical scene in Act I: It is likely the first of many operatic workplace scenes to take place in such a venue. Other workplaces in the opera scenes involve construction laborers, gigging musicians at a nightclub, and farm workers tending the family garden. One of the opera’s themes is that hard work, pain, and “disturbing the earth” are needed for growth. In this hardscrabble world, intimate conversation is culturally forbidden: “Soft talk is for pussies, not men,” Charles’s brothers tell him. “Real men leave things unsaid.”

“There once was a boy,” the libretto relates, “a boy of peculiar grace. The South is no place for a boy with peculiar grace.” The librettist and composer must have had the 1948 Nat King Cole song “Nature Boy” by eden ahbez (pen name for George McGrew) in mind, with its theme, “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn/ Is just to love and be loved in return.” The concluding moments of the opera have mother and son declaring their love finally, unequivocally, to one another, as they sit down for perhaps the first honest conversation of their lives.

Fire Shut Up in My Bones features a most interesting conceit—the young boy Char’es on stage a great deal of the time (performed winningly by Walter Russell III) together with the mature Charles sung by baritone Will Liverman. As we go through life, this idea suggests, we are always accompanied by memories and imprinting of our earlier selves. A similar strategy for representing the real-life character with its imago or spirit also occurs in the recent opera Eurydice by Matthew Aucoin, with a libretto by Sarah Ruhl based on her original play, where Orpheus is also echoed by a super-ego (that opera will be broadcast in live HD transmission from the Met on Dec. 4 in movie theaters nationwide). And Broadway fans will also recall that Fun Home, the three-time Tony Award-winning musical based on the life of lesbian cartoonist Alison Bechdel, also employed a similar technique, but with three performers—child, teenager, and adult—all onstage together.

Another innovation in this libretto is having the Charles character shadowed, as it were, in Act I by Destiny, in Act II by Loneliness, and then in Act III by Greta, the girl he meets at a fraternity party who, it turns out, is committed to another guy. All three of these roles are played by the leading American soprano Angel Blue, commenting on the action almost like the Greek chorus of ancient theater declaiming the inevitability and rightness of his feelings at each stage of Charles’s growth.

When he is attempting to seduce Greta, Charles sings, “Kiss me. Hug me. Love me. See me.”—all that was missing from his childhood—in lyrics that inevitably recall The Who’s Tommy.

The opera has two co-directors: James Robinson, who was brought on from the OTSL premiere of the work, and Camille A. Brown, who choreographed the entire show. Capturing the many distinct ways in which Black people move in dance and gesture was her job. It comes out in the many crowd scenes as well as in the all-male phantasms that torment Charles like harpies before he is able to come to terms with his sexuality, and in the step dance at Charles’s Grambling State University Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity induction. In such ways, Fire set a new bar for “firsts” on stage at the Met going far beyond the ethnicity and musical style of its composer.

Opera has its share of LGBTQ characters, not in proportional numbers to their representation in society overall, but notable. Oscar Wilde, Julius Caesar, Harvey Milk, Countess Martha Geschwitz in Lulu, and many others presumed or presented to be “queer” have appeared in operatic roles. At the end of this coming-of-age story, Charles is able to leave his early resentments and traumas behind as he finally admits, “I am what I am. I am a man.” In just that phrase the newly whole persona summons up the open queerness of the musical La Cage aux Folles’ hit tune, which became almost immediately transformed into the new unofficial gay anthem, and the famous placard from the Memphis sanitary workers’ strike of 1968 when Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, of course for his whole career as a civil rights and anti-war spokesman, but at this particular moment for his labor activism. For Charles to state his truth marks the beginning of a new life of clarity.

The HD transmission features live interviews with performers, the composer, and the conductor, in this case, the Met’s blondined Yannick Nézet-Séguin, who is also the company’s music director, born in Montréal in 1975, and though fully fluent in English, still a charmer with his cultured French-Canadian accent. The conductor led the orchestra clad in a colorful tunic which he explained related to the 1960s and ’70s setting of the opera. Asked what he most enjoyed about this music, he said the popular forms and jazz idiom gave him the opportunity to “dance” on the podium, although in real life he does not consider himself a very good dancer—unlike “my husband,” he hastened to add, who is a great one.

This was not the first time a wider audience had been aware that the musical head of the Met is a gay man, but it was clear that this aspect of his life is definitely not “off-limits.” (The previous music director, the late James Levine, was well-known, though not openly, to be homosexual, and ultimately left the Met under the cloud of lawsuits over his sexual exploitation of any number of young men.) Nézet-Séguin was evidently gushing not just over the immense wealth of African-American “stories” that could now be told at the Met with its newly opened doors (not to mention certain colloquial swear words never heard before on this stage) but the entire range of subject matter that opera had never fully explored. Expect this hoary institution, which by almost universal assessment has lagged behind many of its European counterparts in modernity and daring, to reflect some fresh, bold thinking in the years ahead.

In HD transmission one could see the cameras frequently panning the audience, and a viewer could appreciate that the opera was drawing in a multi-racial and somewhat younger public. This is, infamously, one of the great challenges today in “high art”—opera, theater, the concert hall, ballet, museums—art that oftentimes carries a high price of admission: How to attract younger and more diverse fans. Diversifying and democratizing the art itself is certainly one place to begin. A greater societal investment in the arts, such as we see in European countries, would lower the cost barriers.

See here for further information on the opera, its creator, videos, and more. The trailer can be viewed here. The opera meets the highest affirmation of the famous Kappa Alpha Psi motto: “Achievement in Every Field of Human Endeavor.”