ARLINGTON, Va.—When New York City workers and their allies raised their voices against Amazon’s low pay, lousy working conditions, and hatred of unions, the monster retailer and distributor “picked up its toys and went home,” in the words of one activist. Now it’s Arlington, Virginia’s, turn to see if the same thing will happen.

But as the mostly minority and working-class neighborhood in the otherwise rich D.C. suburb gears up for the fight, its members lack some advantages the New Yorkers had, notably unions and politicians on their side.

And the Virginia state government, which has almost total control over local cities and counties, is already in the tank with Amazon and its owner, Jeff Bezos, one of the three richest people in the U.S.

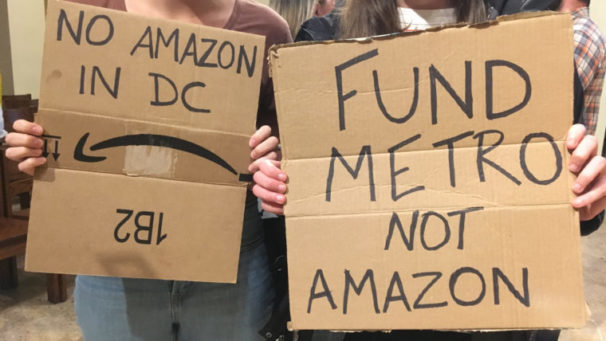

That daunting prospect didn’t stop more than 100 activists and Amazon skeptics from jamming a local restaurant for a community meeting on Feb. 18 to criticize and dissect its bid.

Indeed, they’ve already won one preliminary skirmish with both local pols and the giant corporation. The Arlington County Board had planned to OK Amazon’s bid – after holding two sham “public hearings” on it earlier – on Feb. 23.

But the uproar over lack of consultation with the community and lack of consideration of Amazon’s impact on schools, housing, and transportation forced a postponement until March. That gives Amazon skeptics more time to marshal community opposition, said Dan Zavatevas of the grass-roots Anti-Amazon Coalition, which put the forum together.

Cards and petitions for the county board, opposing Amazon and providing space for a wide range of concerns – from overpriced housing to overcrowded schools to lack of well-paying Amazon jobs for area residents — were part of the Arlington community session.

The saga started last year when Amazon solicited secret bids from around the country for a second headquarters outside its Seattle home. Hundreds of cities jockeyed for HQ2, as it’s called, as Amazon dangled the prospect of 50,000 jobs and what it said would be millions of dollars in long-term positive economic impact before each.

In return, Amazon wanted huge and long tax breaks, large infrastructure investment, a city which could attract the outside high-tech workers it will bring in, and a local commitment to technology education, to provide Amazon with a pipeline of future indoctrinated professionals.

Eventually, Amazon decided to split HQ2 between the New York City borough of Queens – specifically Long Island City – and Arlington, a close-in D.C. suburb with a mix of high-tech workers and working-class African Americans and Latinos. Arlington also has easy access to the nation’s capital and its array of universities, museums, culture, and think tanks.

In both cases, Amazon got top city and state officials in its corner. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and Gov. Andrew Cuomo, both Democrats and supposedly worker allies, pushed hard for Amazon. The state chipped in with $3 billion in subsidies, including tax breaks.

In Virginia, Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam got a $300 million infrastructure bond issue through the GOP-run legislature with virtually no hearings and in quick votes, speakers at the forum explained. Amazon wants another $200 million bond issue from Arlington County.

And in both cases, the target neighborhood for HQ2 features a mix of middle-income and working-class residents, many of them minorities and virtually none of them the “techies” Amazon would import. Arlington’s HQ2 target area houses many Spanish speakers.

Instead, those local residents could seek Amazon’s non-glamorous jobs: Warehouse workers, janitors, cleaners, security officers, and the like — maybe. That assumes the local workers could afford to stay in the area. Speakers at the Arlington forum predicted Amazon-fueled gentrification would probably push housing sky-high and current residents out.

The working class, especially minorities, also toil in Amazon’s warehouses and distribution centers nationwide for low pay and often in awful conditions. None are unionized and Amazon vehemently opposes organizing drives, even among its techies. Nevertheless, extreme heat and cold in one Twin Cities distribution center forced workers, many of them Somali immigrants, into a successful walkout last year to publicize their cause.

But the similarities between New York and Arlington end with the target neighborhoods and the top political leaders’ backing.

In New York, unions split: Teamsters Joint Council 16 and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union opposed the deal. Service Employees Local 32BJ and the building trades supported it, citing Amazon’s promises of jobs, particularly for construction workers under a Project Labor Agreement to build HQ2‘s New York structures.

RWDSU is known for its support of minority and working-class people. Those workers drew some political support, notably from first-year Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., a Democratic Socialist with a huge “new media” following. She opposed Amazon due to its impact on them.

“New Yorkers made it clear Amazon wasn’t welcome in our city if it would not respect our workers and communities,” Joint Council 16 President George Miranda said after Amazon left. “Apparently, the company decided that was too much to ask. We are committed to fighting for the rights of workers throughout the Amazon supply chain and supporting their demand for a voice on the job.”

“If the Amazon deal falls apart, they will have nobody to blame but themselves,” RWDSU President Stuart Appelbaum said before the deal collapsed. “A major problem is the way the deal was put together shrouded in secrecy and ignoring what New Yorkers want and need. They arrogantly continue to refuse to meet with key stakeholders to address concerns.”

“With their long history of abusing workers, partnering with ICE to aid their persecution of immigrant communities” – that issue arose in Virginia, too – “and contributing to gentrification and a major housing crisis in Seattle, New Yorkers are right to raise their concerns and opposition. New Yorkers won’t be bullied by Jeff Bezos, and if Amazon is unwilling to respect workers and communities, it will never be welcome in New York City.”

Faced with the flak, and refusing to even admit the possibility of neutrality during union organizing, Amazon pulled out of the Big Apple. Reportedly, some of the workers it intended for New York City will instead go to a smaller campus in anti-union, right-to-work Tennessee.

The situation is different in Virginia. The building trades are the dominant unions there. After conversations with the Carpenters, Zavatevas reported those unions support Amazon for the same reason construction unions in New York did: Project Labor Agreements to build Arlington’s HQ2 facilities. In contrast to New York, only one of the five Arlington County Board members is skeptical of Amazon’s bid, so far. State and federal lawmakers did not resist.

Amazon also demanded Arlington County bargainers, again behind closed doors, contribute $23 million to improve local schools. “That’s nothing to Amazon,” one person in the crowd commented. “We have a $20 million budget shortage in Arlington this year alone – and that’s significant to us.”

Virginia state lawmakers also promised $7 million each over 10 years to Arlington and Alexandria in affordable housing construction subsidies for Amazon-linked workers. One responder pointed out the money is already in the state budget, so the two local governments would get it anyway, Amazon or not. Besides, $7 million won’t go far: Zavatevas noted Arlington’s median home price is $679,000 and median rent for a modest apartment is $2,400.

And, as another speaker pointed out, Amazon would take 10 years to build up to the 25,000-job level in Arlington. They’re starting with 400 in rented space right now. Of Amazon, he said: “They’re being cagey about what these jobs are. They’re a big black box.”

As a result, with no money promised to add classrooms to overcrowded schools, build more affordable housing or provide better public transit, “It won’t be long before we see the negative impacts” of Amazon, concluded another speaker, who identified himself only by his first name, Rogelio.