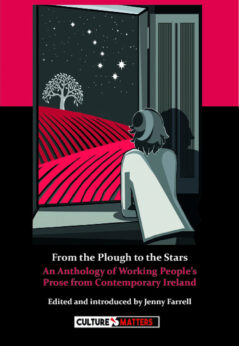

Frequent People’s World contributor Jenny Farrell, based in Ireland, has just edited an important new volume, From the Plough to the Stars: An Anthology of Working People’s Prose from Contemporary Ireland. It is a successor to a similar recent book she also edited of contemporary Irish working-class poetry.

Farrell includes some 50 Irish writers, a few of them now living abroad, publishing them in alphabetical order by last name. Perhaps this was the wisest strategy: If divided by thematic content, a reader might have been tempted to skip over a theme that didn’t grab their attention—a historical section, or one about immigrants in today’s Ireland, or about the ineradicable influence of the Catholic Church. In truth, many of these contributions cannot be so easily categorized anyway.

Other topics that receive multiple iterations include women’s place in society, early family life, growing up and schooling, the presence of immigrants in today’s Ireland, history, union organizing, the ever-present national question in the face of British imperialism both in the Republic and in the North and, of course, the workplace in its infinite permutations, urban and rural. As much of this writing is hot off the press, even COVID-19 makes the occasional appearance: Quarantine worldwide has provided writers the opportunity for such literary endeavors.

In parts, the collection reads almost like a tour guide, as the writers lead us through old working-class districts of Dublin and some of the new estates established to rid the cities of their slums. Other parts of the country, including Northern Ireland, still part of the United Kingdom, are included.

Special note must be taken of the matter of language, for Irish is itself an ancient Celtic tongue which the British did everything within their power to eradicate. Over the centuries, maintenance and survival of the Irish language have become in and of itself a radical, and radicalizing goal of national pride, though as we see, different approaches toward this campaign exist, not surprisingly inflected by class interests and concerns. (Andy Snoddy’s memoir “The Radical Protestant Tradition: A Letter to My Grandchildren” reminds us that the interest in Irish was not restricted to Catholics.) A number of Farrell’s writers are fluent in Irish, and a few of the submissions here are included in that language as well as in English translation (or it could be the other way around, it’s not clear).

Speaking of language, we’ll desist here from our standard practice of Americanizing spelling and let the Irish have the floor to themselves.

The Foreword, by Gerry Murphy, President of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (2019-21), makes an American long for such passionate defense of culture and oppositional politics from some of our own labor hierarchy. Murphy writes, “It is also apt, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, that the true value and critical importance of workers’ contributions to our communities, worldwide, takes center stage. These contributions expose the parasitical captains of industry and their fellow travelers in global finance. The disproportionate impact of the pandemic on working-class, ethnic minority, and other disadvantaged communities confirms the need to fight for fundamental change to the political and economic structures of society, and to achieve this we must struggle on a multitude of fronts. This publication, I believe, represents an essential element in our overall fight to advance the interests of the working class, and I commend it to all of you.”

This reviewer adds, “Hear, hear!”

Jenny Farrell provides an Introduction, reminding us of the 2019 release of the anthology The Children of the Nation, a collection of contemporary poetry from a wide range of working people across the whole of Ireland. “These anthologies are the first of their kind in Ireland. Publishing working people’s voices together in an anthology takes a stand against the mainstream narrative, mainstream educational assumptions, and mainstream cultural sidelining.”

Aside from thematic content, the submissions here fall into a number of genres, altogether creating the collective portrait of a national working class: memoir, short story, flash fiction, history, drama, blog, essay, satire, crime. Each entry is preceded by a short biography of the author, all of whom have strong working-class roots, many of them breaking out as writers only after courageously enrolling in courses or taking university degrees, often the first in their families to do so.

The range of esthetic concerns here is broad, perhaps one might say cosmic. In the words of James Connolly describing the Starry Plough banner of the national movement: “A free Ireland will control its own destiny, from the plough to the stars.” These writers are interested in the human fate from the ground they till so unforgivingly to the heavenly aspirations they summon up in their spirit.

One is tempted to ask—and I will—Isn’t it time for such books in the U.S.?

A reviewer cannot touch on every one of the 50 contributions. A few citations (in alphabetical order) will have to represent them all.

Patrick Bolger’s memoir “Revelation” recalls the clerical abuse to which he was subjected. He later even found photos of himself as a child with the predatory priest used in a documentary without consulting him. “It’s a strange thing about a small country village. Gossip would spread on the wind like a lit fire through the heather and furze on the hills. Some things, however, seemed to be beyond words. Things involving sex and abuse and rape and boys and a priest. They were things that could never be let take light.”

In “Local,” Edward Boyne reflects through the voice of one character what is surely a not uncommon view, and by far not just in Europe today. “Immigrants are a good idea, I don’t mind saying. There’s more of them visible now. Still a bit of a novelty, but we’re getting used to it. We needed a new underclass so we can feel better. That counts for a lot, raises the morale, brings on more spending. It’s all about spending. Not about need. That’s just do-gooder talk. It’s greed not need.”

Brian Campfield held office with the Northern Ireland Public Service Alliance and is a longtime Communist Party of Ireland (CPI) member. “It was another Irish writer and political activist, Brendan Behan, who made the quip that the first item on the agenda of any new political organisation in Ireland was ‘the split,’ such was the almost pathological mentality of the Irish Left to elevate those issues that divided rather than united them. But then, the Irish Left have no more claim to this dubious honour than their counterparts in other countries.” I am sure many readers will know full well of what Campfield speaks.

He goes on in ringing words that might also serve as an epigraph for the whole book: “No stuffed shirts, snobbery or superiority complexes. No saviour from on high was expected to deliver, either in the context of workers’ emancipation or the Irish Language; just the unstinting and unselfish energy and efforts of comrades and activists, anti-sectarian, anti-imperialist, internationalist, struggling not just to decolonise society and the economy but the very mind itself. Many of their stories have still to be told.”

Michael G. Casey, in “Fadings,” writes about Cynthia in a pizza factory just after the sudden death of a workmate. “How difficult it was to perceive absence. She felt bad. A man had stood at that spot for fifteen years doing a menial job, had somehow managed to keep his spirits up, as well as those of his co-workers, and she, Cynthia, could not recall who he was. And she had always prided herself on being a good people-person.”

Among speakers of all the different varieties of English around the world, the Irish hold a high place in their inventive and amusing adaptations. Perhaps it’s their famous “gift of the gab.” In “The Dublin-Meath Saga,” a piece of sports writing about a 1991 soccer match, when she was 10, Gráinne Daly mentions that her father had blown his marriage “by some kink of feckituppery.”

Celia de Fréine is one of the anthology’s writers who is published here in both Irish and English. Her COVID-era flash fiction “A Way in Which to Overturn the Pecking Order?” posits a shipwreck succeeding which the butler ruled on the island. After being rescued and returned home he couldn’t go back to the old ways and left his employ “So that we might stand in a relay of thunderous applause once more to celebrate a future normal in which all lowly-paid, inadequately-clad workers, who risk their lives while looking after the ill and dying, receive their just reward.”

Stephen James Douglas gives us a bit of drama in “Gaia’s Diagnosis,” a terse doctor-patient dialogue, where Gaia is the Earth itself. A speaker LOVELOCK introduces the scene:

“Humans on the Earth behave in some ways like a pathogenic organism, or like the cells of a tumor or neoplasm. We have grown in numbers and disturbance to Gaia, to the point where our presence is perceptibly disturbing… [sic] the human species is now so numerous as to constitute a serious planetary malady. Gaia is suffering from Disseminated Primatemaia, a plague of people.”

GAIA: “Is it terminal?”

DOCTOR: “I’m afraid so.”

In “Mothering Through the Pandemic,” Attracta Fahy speaks of her son living in L.A., working as an anesthesiologist during COVID. Some excerpted passages: “This virus, like a comet, came shooting in, wreaking havoc; every tragic story reflects how susceptible we are to trauma. It’s as if there’s a broken mirror spinning somewhere in orbit, reflecting back the state of our world. Not least, showing us who cares about the vulnerable in our society, and who cares about humanity…. There is a murderous, consoling beauty in nature…. Perhaps we can’t cope with beauty or know how to manage it. Ancient people were good with beauty, particularly the Greeks, but beauty to a capitalist world is something to be coveted or destroyed…. In many ways, this pandemic gave us the opportunity to contemplate, pay more attention to what is important: relationships, family, friendship, and nature. Our ancestors had a wisdom we seem to have taken for granted, forgotten, or made unconscious. We have an opportunity now to make it conscious.”

Declan Geraghty, author of “Nine hour stroll,” writes in his bio: “Ireland has a problem with class prejudice and he hopes to be a part of breaking it with his writing.” He describes most of the jobs you can get these days as “A hamster on the wheel so the government can say you’re productive.”

Anita Gracey from West Belfast is a widely published wheelchair user. She wrote “Sketch of an Atheist” in memory of her brother Brian Gracey, a freethinker and also a wheelchair user who had a socially distanced burial last year. Anita has a unique style of prose poetry, rhymed verses strung out in paragraph format. “God surely wouldn’t dole out disability to him with Spiderman’s invincibility! But two long legs became four wheels; he’d shrug saying what can you do, you put up with it, he had to. He took pride in his independence as a man of wheels, and was stubborn, a warrior strength revealed.”

Rachael Hegarty’s “The Dodgy Box” (a gizmo that allows you to get more channels on TV) takes place in the working-class district of Finglas in Dublin. “Mad high speed bumps and poetic place names equals one interesting neighbourhood.” A middle-class woman comes to purchase one from a hustler in this shifty part of town during the pandemic. “Alright his little business enterprise wasn’t 100% legit, but sure what business was?”

Jennifer Horgan writes of a privileged middle-class family on assignment in Abu Dhabi, where household and nanny help is available from the legions of foreign workers, many from the Philippines and little more than indentured servants. In “Their Daughter’s Bib,” Orla, the wife and mother, feels useless in her otiose life abroad in the expat colony. Her maid Lisa intervenes heroically when one of the children is choking. Shortly after, Lisa asks for a four-month paid-in-advance leave of absence so she can return home to look after her mother who’s having an operation, which may or may not be a scam by someone they’ll never see again. Orla and her husband Eoin are discussing it between themselves. “I suppose we should,” Eoin says. “It’s not like she can go anywhere, unless she wants to leave the country that is. And she has a point. She saved our daughter’s life for fuck’s sake. I suppose it’s the least we can do.”

Jennifer Horgan writes of a privileged middle-class family on assignment in Abu Dhabi, where household and nanny help is available from the legions of foreign workers, many from the Philippines and little more than indentured servants. In “Their Daughter’s Bib,” Orla, the wife and mother, feels useless in her otiose life abroad in the expat colony. Her maid Lisa intervenes heroically when one of the children is choking. Shortly after, Lisa asks for a four-month paid-in-advance leave of absence so she can return home to look after her mother who’s having an operation, which may or may not be a scam by someone they’ll never see again. Orla and her husband Eoin are discussing it between themselves. “I suppose we should,” Eoin says. “It’s not like she can go anywhere, unless she wants to leave the country that is. And she has a point. She saved our daughter’s life for fuck’s sake. I suppose it’s the least we can do.”

Camillus John “was bored and braised in Ballyfermot”—more Irish playfulness with words.

Anne Mac Darby-Beck, in “Sick Day,” provides the perfect description of a “Karen” and the system that enables them. A low-level clerk in the parking ticket division, identified only as “She,” is confronted by a resentful recipient of a ticket: “It was the manager she hated most. The public treat you like a dogsbody. But the manager bent the rules when it suited and then hung you out to dry. They left you wide open, to be sneered at by a woman who believed the rules should not apply to her because she was rich enough to afford a holiday home. The words of her favourite writer came to her: privilege means private law.”

One of writer Tomás Mac Síomóin’s claims to fame is that he translated The Communist Manifesto into Irish, published by the CPI in 1986. In “Ballyfermot Enigma!” he captures life in one of the suburban housing estates around Dublin. A teacher of Irish language in a working-class division, he writes of anti-working-class prejudice in the movement to promote the Irish language, perhaps because there was a distinct left-leaning tendency in it with its obvious overtones of being the inherently “subversive” native language in a colonized land. He speaks of the distinction—which I for one was not aware of—between academic Irish with its great variety of inflections and declensions and the “Native Gaeltacht residents” who “speak a much more simply structured Irish.”

In defense of this evolved language “as it is spoke” today, Mac Síomóin sounds off with credible passion about pedants, snobs, and worshippers of the archaic: “But, would they describe the English of contemporary 20th century masters of prose in that language such as Kurt Vonnegut, J.G. Ballard or Liam O’Flaherty, for example, as being simply the results of the degeneration of the language of Beowulf, Chaucer, and Shakespeare?”

In “Dear Diary,” Bernadette Murphy reflects on what it means to be working-class in her own day, its challenges and toll, yet at the same time the community it creates. “After all, working outside of the home was an opportunity denied to my mother and grandmother!”

Frank Murphy’s “Welcome to Dystopia (Another Handmaid’s Tale)” is a brief satire on telephone answering menus. I could easily hear it in my mind’s ear as shtik in a standup routine. I liked what he wrote in his bio: “Frank worked at just about everything, and knows this is no country to end up on the wrong side of.”

Barbara O’Donnell’s “Thresholds” is the memoir of her sickly New Zealand-born mother who comes to Ireland and marries a publican—that’s the proprietor of a pub. O’Donnell as a girl worked in the family business and is now a hospital worker. “I just swapped one set of anaesthetic drugs for another.”

In Lani O Hanlon’s “If You Were the Only Girl,” the author examines the women in her life and what defined them. “Beyond these roles that we are all assigned: mother, daughter, sister, granddaughter, grandmother, there are women with their own inner lives and stories, and there are so many questions that I want to ask; but for most of my life I was looking the other way, away from the matrilineal line….”

Mícheál Ó hAodha writes in Irish and English, is the author of poetry and history, and also is a translator. His essay “Limerick and the World: The Limerick Soviet, and the Legacy of 1919,” included as one contribution to a larger book on that subject (which I knew nothing about), sounds fascinating. In his story “Gone,” the writer, writing in the first person, observes Johnny, a tramp who has been camping out at the train station since he arrived there some five years before. It turns out Johnny was someone he knew from his childhood. Reminiscing about those times: “It was different in those days because nobody wanted to remain aloof. There was no honour in remaining aloof. We all felt part of something, even if it was unnamed and broken.”

Eoin Ó Murchú is a left-wing journalist brought up in London as part of a whole Irish clan cut off from their homeland for several generations, but not from their roots. He heard all the stories from the Old Sod, about how peasants and workers had to suck up to their superiors. Of his story “Memory,” he says it “might throw some contemporary light on why so many young Moslems and South Asians are totally alienated from the English society in which they live.”

“When I was about four years old or so, I wanted my father to stay home playing with me (he was a shift worker on the buses). But he said that Sir wouldn’t let him. Don’t mind Sir, I said. Oh, I must he replied, or else Sir wouldn’t let us have any food, just like the landlords had with our ancestors, and we would be hungry.

“I was furious. I promised my father that when I grew up I would punch Sir on the nose.

“He laughed, but really I’ve been trying to give Sir that punch ever since, and still am. And part of that effort is taking back my native language.”

Karl Parkinson’s “Deano And The Boys From The Block: Word portrait of an inner city youth” is one of the longest stories in the book, about violent, amoral street drug dealer Dean Baker, set in the scene of his derelict environment, not portrayed sympathetically in any way. Yet here is how the author concludes it (sorry, spoiler alert!) in tones and a sharp shift of voice that call up the spirits of William Blake and place the protagonist in a world that could be Hogarth’s, John Gay’s, or Daniel Defoe’s:

“Dean Baker, demon child, brutalised brain, mind full of vipers and black widow spiders. Dean Baker, a wrong un, brought up with fists and boots, fatherless child, council estate concrete soul, street child, falling from the light for too long. Dean Baker, what made thee such a beastly child, what made thee to walk amongst the civilised? If thou hadst been born at sea, or cast unto the Spartans of old, wouldst thou have been different, and not born to this new century, here with us? What made thee, Deano, what made thee as thou art, now? Some darkness at the edge of the Kingdom, creeping towards the center, trailing bodies, trees, cities in its wake?”

Moya Roddy breaks through age, loneliness, and alienation in “They also serve who only….” Old Maeve resists joining the local demonstrations against water charges, mostly out of apathy. She gives the protesters some water for tea, and yet feels a little miffed that the girl at her door didn’t ask her to join the protest. But one day she bakes some scones for the protesters, and they’re gobbled up. “Maeve heads back across the road, heart swelling, blood pumping like mad around her body. She’s never felt—what?—so alive. Alive and useful. As she lets herself in the front door she smiles. Tomorrow morning can’t come quickly enough.”

Jim Ward takes up the subject of immigrants in “Evelyn—after James Joyce.” Evelyn is a young Polish waitress in an Irish working-class restaurant who grew up in post-Communist Poland. She is not especially politically-minded, but she also has her eyes and ears open. “Her father, a devout catholic, often told her about those days. ‘They, the communists were bad people,’ he would say. ‘They had no god.’ He did not like communists, though he had held a permanent job under the old regime, and under it would not have had to send his only daughter to a foreign country as he had her.”

Evelyn has a friendship with Paul, a member of the Irish Revolutionary Workers’ Movement, which to her eyes, when she attends some of their small meetings, seems pretentious, all guys, and hardly working-class. “Maybe, she thought, they would attract more members if instead of endlessly deliberating about dogma, they campaigned on wages and conditions.” Paul keeps enticing her to come with him to England to work in the ill-defined “entertainment industry.” Her not quite conscious proletarian instincts kick in.

We’ll end where we started, with what appears to be a first-person story about the Catholic Church. Anne Waters’s “St. Stephen’s Day” relates a tragic story about the crocheted blue baby bootees, a mystery found when she opens her late mother’s shoebox of little treasures. Her Aunt Ellen would know about these.

“‘We left her in a Magdalen Laundry, in Dublin. Of course, at that time, we didn’t know the reality of the “Laundries.” We all thought the nuns were wonderful, caring for fallen, sinful women and their babies. Oh, how foolish and stupid we were.’ A sigh of deep despair escaped Ellen. Drawing breath, she muttered sarcastically, ‘men were blameless apparently, and at the mercy of women, all sexual sirens who seduced them against their will.’”

Readers will discover their own nuggets, treasures, and gems amongst this cornucopia of honest, unsentimental writing. This is of necessity but a brief introduction. Since there is no continuity as such from one story to the next, especially in light of their alphabetical organization, I found it possible to put this book down and ponder about many of these stories for a while before moving on. Its rewards are myriad and gratifying, a bright light of insight into modern Ireland, its dramatic history, and resourceful people.

Culture Matters received welcome support and assistance on this publication from INTO, the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation; USDAW, the Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers; the National Education Union; and the Cork and Fermanagh Trades Councils.

From the Plough to the Stars:

An Anthology of Working People’s Prose from Contemporary Ireland

Edited and introduced by Jenny Farrell

Foreword by Gerry Murphy

Culture Matters Co-Operative Ltd, 2020

ISBN 978-1-912710-36-2