FLINT, Mich. — The Holy Spirit of Solidarity compelled Jake, a 43-year UAW member, and General Motors worker, to go out onto the picket line. Well, that, and his upcoming retirement on Jan. 1, 2020.

“We’ve got to make sure we leave something good behind for the next generation,” he said, head looking down, hands cupped around the small yellow flame about to light his cigarette.

“We’re making history here, I suppose… If not, it’ll still be a good story to tell the grandchildren.”

He paused, visible exhaustion written across each wrinkle and line on his face, as he took a slow drag of burning tobacco.

“I’ll be happy when this is all over…happy and content, retired in Florida with my wife,” he continued. “But don’t get me wrong, I’m glad we stayed out on strike after they reached a tentative agreement. It was smart; lets GM know we mean business this time around.”

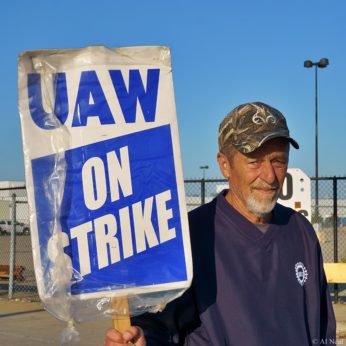

Outside the Flint Truck Assembly plant—the only main GM plant now—around 20 UAW members watched as the sun began to set. Their picket line shifts would end within the hour, and thoughts of cold beer and the UAW/GM tentative agreement began to take hold.

Workers were overheard expressing hopes the “damn thing (contract) is voted through” while others remained determined to vote no. To stay out on strike, and “get something better for the second-tier guys.”

Across every striking plant and within every UAW union hall this same conversation was taking place. The “old-timers” were fighting to punch out—union strong, one last time. The new generation was committed to punching back in, fighting to keep those retirement benefits, wages, and working conditions.

The evening quiet set in. Two strikers took a seat by the chainlink fence, “no better spot to rest aching knees,” while some inched closer to the street, picket signs angled for a good drive-by view.

And staring out from the plant’s main entrance, it was hard to imagine the massive GM auto manufacturing complex, Buick City, mecca of the industry, that called Flint home for 106 years.

“GM may have built the city of Flint, but it was the UAW, the union, that made it home,” said one worker. “We have to remember and thank all them that were involved in the sit-down… We wouldn’t have a damn thing here if it weren’t for them.”

GM is cold and heartless, like the products rolling off its line, all metal and steel. The labor movement, and this strike, on the other hand, are made of flesh and bone. Strengthened by the virtue of solidarity—spurring working people to action and eventual victory.

Such is the history of Flint, Michigan.

“When the bosses won’t talk, don’t take a walk…Sit down! Sit Down!”

The year was 1936. The United Automobile Workers union was barely a year old. And it had been quite a lackluster year for President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal recovery. Economic conditions were worsening for the working class, and the company bosses began to amp up their offensive once more. Speed-ups, wage cuts, blacklisting, and lack of job security contributed to the growing wave of unionization and strike activity.

From its founding convention, the UAW was poised to organize GM.

By the time November rolled around that year, workers, acting as one, began to slow down, stop work, and eventually sit-down for better wages, benefits, and union recognition.

At a small GM plant, on the outskirts of Atlanta, members of UAW Local 34 sat down.

“Ours was the first plant that went on strike,” said UAW Local 34 president Charlie Gillum, during a 1973 interview with historians Neill Herring and Sue Thrasher.

“Of course, we were crazy,” he continued. “We formed a union out there because, in those days when a fellow went to work, he had no security of any kind…. The fact that people just got so tired of being pushed around is what helped us organize the entire plant.”

Press credited Wyndham Mortimer, first vice-president of the UAW and member of the Communist Party USA, for the success of the sit-down strike. Straight from the get-go, Mortimer headed to Flint to begin building the union and preparing for a massive strike. The will of independently organized workers rushed things a bit, giving the union the jolt of energy it needed. Organizing in Flint, a GM company town, was a dangerous business.

With police on the payroll and spies within the workers’ ranks, Mortimer and union workers began meeting workers at their homes—often in the basement, with only a single burning candle for lighting.

Inside Fisher Body Plant 1, Mortimer built a solid organizing committee with Bud Simmons, Walt Moore, Jay Green, and Joe Devitt, all Communists.

The historic Flint strike officially began on Dec. 30, 1936, when GM workers barricaded themselves inside the plant. The 44-day strike also relied on the organizing skills of their communities, wives, mothers, grandmothers, and sisters, in particular, the UAW’s Women’s Auxiliary and Emergency Brigade.

When food and supplies were needed inside the occupied plants, the Women’s Auxiliary was actively collecting funds, food, and support for the workers inside. When police launched tear gas canisters into the plants to forcefully evict the workers, the women began “breaking the windows so their husbands could get air,” said Arthur Lowell, 92, a veteran of the Flint strike.

The violence and fear of violence from Flint police or the National Guard forced workers to defend themselves any way they could.

“We had some two-by-twos in the corner because we expected at any time to be raided. But fortunately, we weren’t,” said Geraldine Blankinship.

In the end, the UAW and GM, with Michigan Gov. Frank Murphy acting as an intermediary, reached an agreement on Feb.11, 1937. It recognized the UAW, gave workers a 5% pay increase, and more important, helped launch organizing drives across all industrial sectors.

It’s safe to say without Flint, Atlanta, and the other fightbacks of those years, none of the benefits GM workers are fighting to save today would exist.

Reliving history at the Royal Kebab

Sean Crawford came into the restaurant wearing his UAW Local 22 hoodie. He was tired, concerned about the recently announced UAW/GM tentative agreement, and wondered what came next.

Over the smell of Arabic coffee, strong and bitter, hummus and falafel, we sat and talked of all things UAW related—often forgetting this was an interview, courtesy of an innate familiarity between two people joined in a singular cause.

“So, tell me about your family story with the UAW,” I said.

“Well…my great-great-grandmother led a sit-down strike at a textile manufacturing plant, not sure which one, but that’s what my great-aunt Gerry told me,” Crawford said.

“That’s my great-aunt Gerry, Geraldine Blankinship, she was part of the UAW’s Women’s Auxiliary while my grandmother was part of the emergency brigade.”

Crawford’s great-uncle was Jay Green, vice-chair of the Flint sit-down strike in Fisher Plant 1 (mentioned above). Green and Crawford’s other great-uncle, Monroe Blankinship, were both strike leaders in the Fisher plant.

“My grandfather was involved with the union at the time, too, and all his brothers, so it was a family effort. The family was involved in the strike and in building the union at that time.”

It was this history of radicalism and unionism which formed much of Crawford’s worldview, as he continues the family legacy within the UAW.

“My mom was a single mom, so my great-aunt and grandmother spent a lot of time babysitting me. I credit them for how I turned out to a large extent and why I consider myself a socialist,” he said. “They always told me about the strike, the politics surrounding it, and taught me about always talking about current events, like NAFTA, which turned me off from the Democratic Party at a young age.”

We both paused to take a few bites of food before starting up again.

“When we spoke on the phone,” I said, “you mentioned you weren’t happy with the proposed agreement. How come?”

“Well, there are a few quite bothersome issues,” he said. “The main ones making me want to vote no, the ones I feel are not negotiable, are wage equality in the contract for temporary and outsourced employees—under different agreements in the same plant and union who are being exploited daily—and that second-tier employees need to be brought up to full wage scale.

“Everyone needs to be brought together as equals. I feel like for us to advance as a movement we have to embody the principle of solidarity and make people equal and not just have it be rhetoric.”

Job security was the other main issue. We both looked over the agreement and saw no mention of GM’s future investments in North America, or where jobs will be created during the life of the agreement.

“Our communities need jobs to survive and move forward, and we can’t expect to organize any new plants if there’s no job security and wage equality in this agreement. Where’s the reason for people to join the union if they see we aren’t practicing what we preach?” he asked.

There was mention of another labor-management committee to be created for addressing the issues of technology and automation, but as Crawford sees it: “I’m honestly really sick of the joint programs with management. We need a union that’s closer to the membership; management and joint programs is not going to achieve that. Joint programs should be UAW leadership coming to the shop floor and meeting with the local members and committees.”

As the server came by with the bill, and we both checked the time, I asked Crawford about the UAW’s GM strike impact. What did it mean to him?

“This strike is definitely historic for the UAW, not sure if it’s setting the ‘strike standard’ nationwide, but these strikes happening now are setting the standard for tomorrow. They show the depth of community support for workers across industries, the unity between unions and community organizations, and lend credence to advancing discussion on internationalism and international solidarity. You can’t fight an international company without international solidarity; you’ll never win if you’re always whipsawed by your brothers and sisters overseas.”

The UAW/GM contract was ratified Oct. 28. Fifty-seven percent of the UAW gave it a thumbs up. Not every autoworker is happy, especially those in the three manufacturing plants still slated to close.

Looking forward, for the next four years at least, GM workers have made it clear they won’t be pushed around. And as workers nationwide continue taking to the streets and picket lines, demanding better pay, better benefits, and respect on the job, corporate CEOs should be trembling, if they’re not already.

Worker solidarity has returned with a wicked vengeance.