BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP) — The federal government has reopened its investigation into the slaying of Emmett Till, the Black teenager whose brutal killing in Mississippi shocked the world and helped inspire the Civil Rights Movement more than 60 years ago.

The Justice Department told Congress in a report in March that it is reinvestigating Till’s slaying in Money, Mississippi, in 1955 after receiving “new information.” The case was closed in 2007 with authorities saying the suspects were dead; a state grand jury didn’t file any new charges.

Deborah Watts, a cousin of Till’s, said she was unaware the case had been reopened until contacted Wednesday by The Associated Press.

The federal report, sent annually to lawmakers under a law that bears Till’s name, does not indicate what the new information might be.

But it was issued in late March after the publication last year of The Blood of Emmett Till, a book that says a key figure in the case acknowledged lying about events preceding the slaying of the 14-year-old youth from Chicago.

A Mississippi prosecutor declined comment Thursday on whether federal authorities had given him new information since they reopened the probe.

“It’s probably always an open case until all the parties have passed away,” said District Attorney Dewayne Richardson, whose circuit includes the community where Till was abducted.

Richardson said if a case were to move forward, he and the district attorney in the county where Till’s body was found could decide who would prosecute it.

The book, by Timothy B. Tyson, quotes a white woman, Carolyn Donham, as acknowledging during a 2008 interview that she wasn’t truthful when she testified that Till grabbed her, whistled, and made sexual advances at a store in 1955.

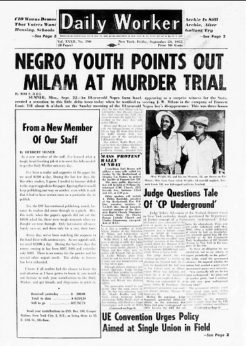

Two white men—Donham’s then-husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother, J.W. Milam—were charged with murder but acquitted in the slaying of Till, who had been staying with relatives in northern Mississippi at the time. The men later confessed to the crime in a magazine interview but weren’t retried. Both are now dead.

Donham, who turns 84 this month, lives in Raleigh, North Carolina. A man who came to the door at her residence declined to comment about the FBI reopening the investigation.

“We don’t want to talk to you,” the man said before going back inside.

Paula Johnson, co-director of an academic group that reviews unsolved civil rights slayings, said she can’t think of anything other than Tyson’s book that could have prompted the Justice Department to reopen the Till investigation.

“We’re happy to have that be the case so that ultimately or finally someone can be held responsible for his murder,” said Johnson, who leads the Cold Case Justice Initiative at Syracuse University.

The Justice Department declined to comment on the status of the investigation.

The government has investigated 115 cases involving 128 victims under the “cold case” law named for Till, the report said. Only one resulted in a federal conviction since the act became law, that of Ku Klux Klansman James Ford Seale for kidnapping two Black teenagers, Charles Moore and Henry Dee, who were killed in Mississippi in 1964. At least 109 of the investigations have been closed, the report said.

State prosecutions assisted by federal authorities have resulted in additional convictions, most recently when a one-time Alabama state trooper was convicted of shooting a Black man, Jimmie Lee Jackson, during a protest in 1965. Jackson’s slaying was an impetus for the Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march later that year.

Watts, co-founder of the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation, said it’s “wonderful” her cousin’s killing is getting another look, but she didn’t want to discuss details.

“None of us wants to do anything that jeopardizes any investigation or impedes, but we are also very interested in justice being done,” she said.

Abducted from the home where he was staying, Till was beaten and shot, and his body was found weighted down with a cotton gin fan in the Tallahatchie River. His mother, Mamie Till, had his casket left open. Images of his mutilated body gave witness to the depth of racial hatred in the Deep South and helped build momentum for subsequent civil rights campaigns.

Relatives of Till pushed Attorney General Jeff Sessions to reopen the case last year after publication of the book.

Donham, then 21 years old and known as Carolyn Bryant, testified in 1955 as a prospective defense witness in the trial of Bryant and Milam. With jurors out of the courtroom, she said a “n—-r man” she didn’t know took her by the arm and detailed what was allegedly said to her.

A judge ruled the testimony inadmissible. An all-white jury freed her husband and the other man even without it. Testimony indicated a woman might have been in a car with Bryant and Milam when they abducted Till, but no one else was ever charged.

In the book, author Tyson wrote that Donham told him her testimony about Till accosting her wasn’t true.

“Nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him,” the book quotes her as saying.

Sen. Doug Jones, D-Ala., introduced legislation this week that would make the government release information about unsolved civil rights killings. In an interview, Jones said the Till killing or any other case likely wouldn’t be covered by this legislation if authorities were actively investigating.

“You’d have to leave it to the judgment of some of the law enforcement agencies that are involved or the commission that would be created” to consider materials for release, Jones said.

Associated Press writers Emily Wagster Pettus in Jackson, Mississippi, and Allen G. Breed in Raleigh, North Carolina, contributed to this report.