On the eve of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland declared that a newly created Missing and Murdered Unit in the Bureau of Indian Affairs is determined “to solve the crisis” of thousands of unsolved cases that still leave families without justice or closure.

For decades, the number of Indigenous persons—women and girls in particular—who have disappeared or been killed with no suspects arrested have piled up. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control, among American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls aged 10 to 24, homicide is the third leading cause of death. In some states, such as Montana, Indigenous people account for more than a quarter of missing persons cases, though they make up less than a tenth of the population.

Haaland, who made history when she became the first Indigenous Cabinet secretary in March, said Tuesday, “For too long this issue has been swept under the rug.” She said that the time of Native issues being shunted aside to small and powerless tribal offices within various government agencies was over. She declared that going forward, Washington would take a “whole-of-government” approach and that Native leaders would themselves be at the fore.

“Every federal agency is taking our commitment to strengthening tribal agency and self-government seriously,” Haaland said. The priority for the Missing and Murdered Unit will be closing unsolved cases, working in conjunction with families and tribal leaders to gather data and evidence.

The disappearances and murders are often linked to causes ranging from domestic violence and dating violence to sexual assault, stalking, and sex trafficking. But these general indicators of gender-based violence intersect with factors specific to Indigenous lived experience.

On reservations and in rural areas, for instance, remoteness combined with proximity to major cross-country highways that serve as trafficking conduits often make victims appear as easy targets. It’s estimated that on some reservations, the murder rate of Native women could be over ten times the national average. Poor cell phone service, the small number of law enforcement in these areas, and complicated jurisdiction boundaries are also factors exacerbating the situation.

Nearly three-quarters of Indigenous people in the U.S., though, live off federally defined tribal lands, usually in urban areas. The same lack of prosecution, poor record-keeping, and institutional racism that hamper rural investigations also figure in the cities. Missing persons laws and police department policies concerning when a person can be considered missing are inconsistent and also contribute to the problem.

Quantifying the true scale of the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women, however, is next to impossible because of notoriously faulty and incomplete data. A snapshot study by the Urban Indian Health Institute, for example, found that of the 5,712 cases it was able to document in the year 2016, only 116 of them were logged in the Department of Justice’s national database—a mere 2%.

Racial misclassification adds to the problem of unreliable statistics. A New York Times investigation found that Native women “are often misclassified as Hispanic or Asian or other racial categories on missing-persons forms,” thus potentially leaving thousands more out of federal databases and understating the magnitude of the crisis.

Taken together at the macro level, the Urban Indian Health Institute says the problem is the result of “a deeply flawed institutional system rooted in colonial relationships that marginalize and disenfranchise people of color and remains complicit in violence targeting American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls.” Raising public awareness of the crisis remains a challenge, though, as more than 95% of cases never receive national or international news media coverage.

That’s why Haaland’s establishment of the Missing and Murdered Unit is crucial for amplifying national attention to the issue as well as solving cases—two things that are intertwined. Bryan Newland, the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, said Tuesday that the unit “will allow us to coordinate our resources across the nation” to both re-examine old cases and tackle new ones as soon as they arise.

Haaland says the Interior Department will evaluate the unit’s success by how many cases it can close. “Right now there are people in this country who don’t know where their loved ones are…. We want to be able to answer that question, we want to make sure that folks have closure.”

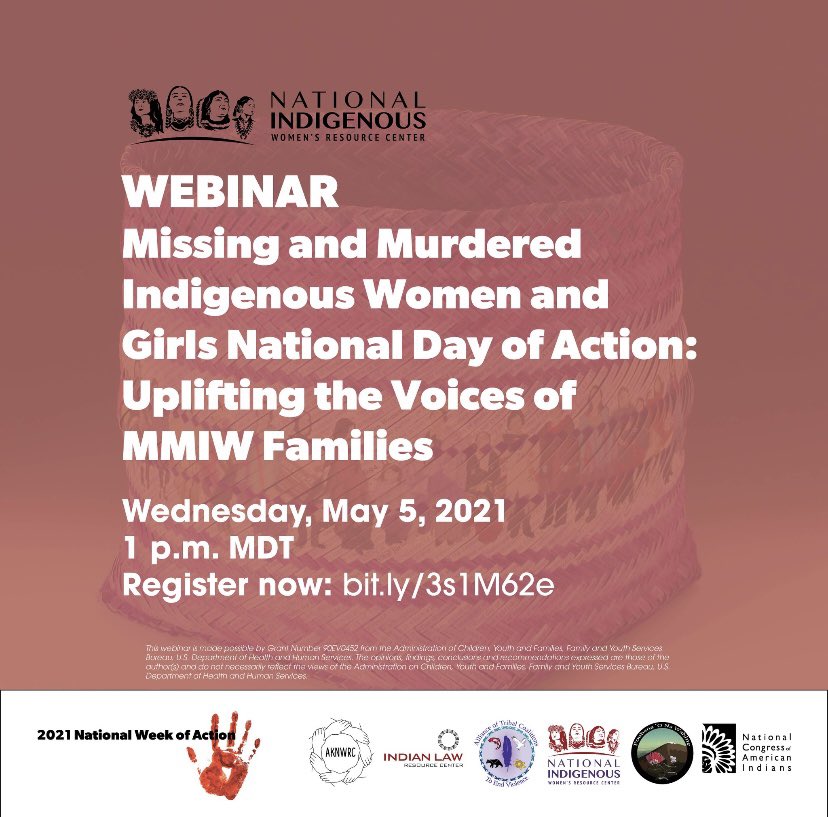

Haaland’s move received a further boost with an official proclamation by President Joe Biden marking May 5, 2021, as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day. In a signed statement, Biden declared, “Our failure to allocate the necessary resources and muster the necessary commitment to addressing and preventing this ongoing tragedy not only demeans the dignity and humanity of each person who goes missing or is murdered, it sends pain and shockwaves across our Tribal communities.”

He said that the treaty and trust responsibilities of the federal government to Tribal Nations require a total revamp and that cooperation with Indigenous communities on a Nation-to-Nation basis is required to tackle the crisis.

The administration is already putting up the resources to back Haaland’s initiative. It will commit six times more money than what was made available for investigating the missing and murdered issue by former President Donald Trump. In its last days, the Trump administration said it would look into the issue further, but most Native leaders took a wait-and-see approach.

Recent white supremacist and anti-Native statements by former Pennsylvania Republican Sen. Rick Santorum have only served to sour many Indigenous activists on the GOP, however. “We birthed a nation from nothing. I mean, there was nothing here,” Santorum told students at a conservative youth meeting in April. “I mean, yes, we have Native Americans, but candidly, there isn’t much Native American culture in American culture.”

Thanks to the trouncing of Trump in the 2020 elections, Santorum’s party is completely removed from any influence over executive branch policy. Haaland’s establishment of the Missing and Murdered Unit and the Biden administration’s commitment of resources are intended as signals that the U.S. government is now in it for the long haul and won’t let up.

“We’ll keep working until our people stop going missing without a trace,” she pledged.