One of the highest pinnacles of my 15-year career as Southern California Director of The Workmen’s Circle/Arbeter Ring (WC/AR or WC) took place the afternoon of January 6, 2008, when the organization held a grand celebration of our uninterrupted 100 years of existence in Southern California. The national organization had been founded in New York City in 1900 as a secular, socialist, Yiddish-speaking expression of Jewishness closely aligned with the Bund in Europe. The Forverts newspaper (much later adding an English version The Forward) closely mirrored its global outlook, which in the mid-1920s, and especially after the rise of Joseph Stalin, turned militantly anti-Communist, with but a temporary pause during World War II to help win the war.

Within the span of a very few years, branches popped up all over the U.S. and Canada. San Francisco’s was the first in California, just a few months earlier in 1907, followed shortly by Los Angeles in 1908.

How Ed Asner came to be our keynote speaker that day requires a little background.

In 1995 I’d been unemployed for a full two years already, feeling washed up and useless, and still grieving the loss of my partner Rick to AIDS in 1993. My doctorate in history, the fact that I had already published a book and hundreds of journalistic articles, almost militated against my finding work—any work—because I was evidently overqualified for anything I applied for.

Thus it was a turning point in my life when the Southern California District accepted my strong qualifications to become its new regional director in November 1995. The local board reviewed my résumé and openly entertained their suspicions about me—biographer of two former Communist composers (Marc Blitzstein and the pending co-written autobiography of Earl Robinson) and a named editorial advisor to Jewish Currents magazine, founded in 1946 as a Communist Party organ but which separated from the party in the 1950s, still embracing its anti-imperialism. It had been one of the primary outlets for my (unpaid) writing for about a decade already.

The SoCal District had gone through a long, dispiriting series of directors, none of whom could satisfy the board’s aspirations which, not to be too unkind, amounted essentially to retaining the tired ascendancy of the old-timers and their fusty social-democratic politics of the 1940s-1960s, while somehow attracting a new cadre of younger members to keep that particular flame alive. I was pointedly asked if I could serve WC/AR loyally without imposing my own political views and, remembering the defiant socialism of the organization’s early years and trying to set aside its endorsement of the Vietnam War that I had militantly opposed, I honestly said yes.

As my first item of business, I prepared a press release on my appointment, including highlights of my life, quoting myself about the “venerable organization founded in 1900 on high ideals. I believe the time for putting those ideals into action is not over. In fact, as the militant right wing seeks to turn this country back to the unrestrained exploitation of a century ago, the need for working people and middle-class professionals to come together in self-defense is greater than ever.”

One of the first strategic appeals that I made was to reach out to those elements of the defunct Jewish Communist left in L.A., or their children, for whom the secular, Yiddishist WC could be their logical future home. Out of these and other new recruits to the organization I intended to develop a new generation of activists to take on a sense of ownership of the organization, and over time assume control, not in the sense of a takeover or coup, but simply as a normal, organic evolution.

If my campaign to transform WC with a new infusion of more open-minded, politically woke, left-wing, artsy and sexually rebellious members (people like me!) could produce some results in L.A., why not nationally? I started thinking about ways in which the Jewish Currents readership could be brought closer to WC. I learned that the WC bookstore in New York did carry Jewish Currents and that they permitted use of their space by certain Yiddishists to their left. In my mind, such a rapprochement could spell the demise of the fateful decades-long alienation not just between the Socialists and the Communists in Jewish America, but among all their children who grew up with certain prejudices against the other, and the various organizations, media, and successor organizations that sprang out of these divergent traditions.

One such group in L.A., for example, was the Sholem Community, led by former Communist Hershl Hartman, which conducted a secular Sunday school for Jewish and mixed-background kids. That school emerged in the early 1950s out of the Communist Jewish left and competed with our WC shule (school in Yiddish). Our shule closed down around 1980—toward the end with only half a dozen students—and I could foresee a day when these two communities might come together, symbolizing the healing of that terrible, destructive wound between us, and regenerating a new vision of secular Jewish life. To those folks, they represented the “left” of the left, while WC with its allies were the “right” of the left. I considered it a coup each time I recruited any of these former Commies or red-diaper babies to WC, not as “one for my side,” but as an expression of hope in an optimistic joint future.

As a historian by training, I could readily appreciate that the hardened antipathies of one faction against the other each had their legitimate reasons, at the same time feeling that now, with the fall of the Soviet Union, it was high time to reassess the burden of holding onto these ancient grudges that meant little to nothing to younger people.

With my “Martian eyes” looking at the hoary protocols of WC, I could see some things that badly needed change. To mention one small example, I pointed out to my boss in New York that our national membership form, which I eagerly put into the hands of prospective new recruits, had room for two names: “Member” and “Spouse” (as if the “spouse”—presumptively the wife—was not or could not also be a member). How offensive that looked to an unmarried couple, or to anyone in the LGBT community (there was no Q then)! They revised the form almost immediately, and I think were grateful to have someone come in from the outside, as it were, with a new point of view. I had the feeling I could genuinely make a difference.

I held a New Year’s cum birthday party at WC and prepared a speech outlining my drive toward forging a common progressive vision of what needs to be done in America and sent copies to over 150 of my friends, in a far-flung appeal for activists of my generation to join WC and help re-create it into a modern, fresh-thinking, progressive and meaningful force comparable to what it had been in earlier decades. I believed it required the infusion of the “New Left” and younger people to make this happen. Among others, playwright Tony Kushner joined WC at my urging.

Jewish Currents liked my speech, and I adapted it into an article, “The Workmen’s Circle: My (Our) Future,” appearing in the February 1997 issue. That article, and other conversations I had with him, prompted Morris Schappes, longtime editor and renowned former Communist, to publicly join WC in New York, actually starting a Jewish Currents branch. The process of breaching the old divide was underway. For a short time, until the financial burden became too onerous, WC actually became the formal publisher of Jewish Currents. The two opposing camps had become a single force at last!

What about Ed Asner?

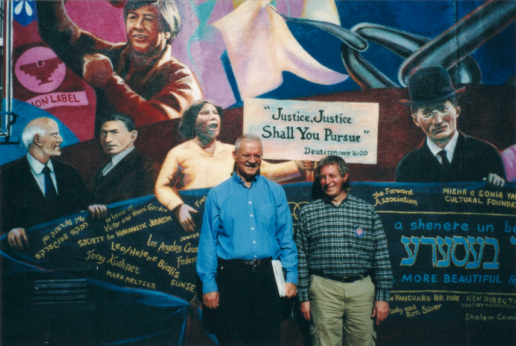

Fifteen years of my life and professional career can hardly be summed up in a short article. We lavished great investment in a 70-foot mural on the outside of our building, and we established A More Beautiful World—A Shenere Velt—Gallery in our main meeting hall where we mounted 100 or so different art shows. But I did promise to speak about Ed Asner after all.

Before I arrived at WC, it had painted itself into a tiny corner together with the Jewish Labor Committee, the L.A. Yiddish Culture Club, and fellow Forverts readers—not much of a coalition to build upon. Suddenly we had fresh winds blowing through our windows and all kinds of lefty groups started to discover our welcome mat. Occasionally, if we co-hosted a talk about U.S. policy in Central America, for example, a celebrity associated with our co-sponsor, someone the likes of the radical Ed Asner, might show up. So I did cross paths with him more than once. The Los Angeles Times obituary for him on Mon., Aug. 30, the day after he passed at the age of 91, quoted him as saying, in 2010, “I’m always thought of in Hollywood and surrounding environs as the resident communist.” Which I don’t believe he meant literally (though clearly, he didn’t reject the term), but only as a statement of how he was perceived.

So the commemoration of our centennial in SoCal, at the glorious, newly opened modern Skirball Cultural Center that afternoon of January 6, 2008, will always remain a high point of my career at WC, indeed, of my life, a culmination, for me personally, of all I had tried to accomplish at WC. Speakers from our national organization came, my family all flew in, our choruses sang, and we filled nearly every one of the auditorium’s 300 seats. People came out of the woodwork to honor our 100 years of positive contributions to the life of our community.

As our keynote speaker, which of course would be a further draw to the event, I invited Ed Asner, who represented in Hollywood the perfect fusion of art, responsible social activism on a global stage, and intensely devoted Jewish pride—perhaps the single largest source of his consciousness. I asked him to talk about why the idea of a “left” is still a necessary component of our national life, and he agreed. But under one condition, which his people communicated to me a couple of weeks before the date. I would have to write his speech! And when he stood at the podium he would personally elaborate upon it, add a few personal memories, observations, and jokes, and seamlessly make it his own.

Which, come the day, he performed brilliantly, and no one but my immediate intimates and family was any the wiser.

Later I heard some of the Sholem Community folks snickering about the nerve—the khutspe!—of Workmen’s Circle now claiming the mantle of the “left” in America! Who were they trying to fool, erasing who the real “left” was?!

It didn’t matter anymore. I’ve been retired for 10 years already. Workmen’s Circle has now (belatedly, but finally) legally changed its name to Workers Circle, which was itself a victory not just for the new, anti-sexist generation but for those who, while they were considering a name change, insisted on preserving the organization’s working-class identity despite the enormous transformation of Jewish life in America over the course of 121 years. Its newsletter features photos of its shule kids and their adult leaders at anti-war demonstrations, protests for tenants and the poor, hunger relief, and so forth.

With the help of people like Ed Asner, we left the organization a better one for our efforts.

Main photo credit: Gage Skidmore / Creative Commons 2.0