*Spoiler-free but some discussion of character, themes, and minor plot points.

No one will call Hereditary, the directorial debut of Ari Aster, a simple haunted house story. Most viewers, even the most devoted horror fans, don’t really know what to make of Aster’s chilling new film. But it’s difficult not to see the house as integral to the story’s menace, something the camera encourages in the opening scene as it listlessly pans across the artist’s workshop of Annie (Toni Collette). The shot settles on one of her dollhouse-like constructions, zooming in to enclose us in the real room of a child being awakened for their grandmother’s funeral.

The house in Hereditary is wood-paneled, arts and crafts, and perfectly appointed. It’s not the old dark house, nor is it the cabin in the woods. It’s not even exactly the suburbs but really the exurbs of the upper middle class, not unlike the frightening McEstate of the Armitage family in Get Out, where money buys the dubious pleasure of an atomized life.

What happens in this house unsettles us deeply even before some traditional genre tropes appear. There’s nothing predictable about Hereditary. If you are expecting a slasher film or a riff on The Conjuring, you are in every way unprepared for what the director would like to do to you. Something creeps up your spine in the small, quiet moments that begin the film, a family frozen in their interactions with each other, poisoned by secrets, unable to relate in any meaningful way, and seemingly as cut off from social reality as their home appears cut off from the world.

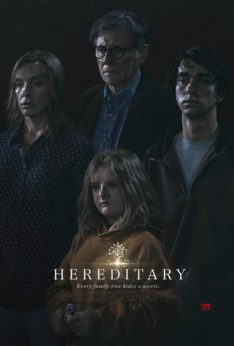

Not everyone has been happy with this film. I suspect that some hoped for a few more jump scares, particularly in the narrative’s long quiet stretches. Instead, the taunt arguments of Stephen (Gabriel Byrne) and Collette’s Annie interrupt the sequestered family’s life more than things going bump in the night. The abstracted demeanor of the young daughter Charlie (Milly Shapiro) and the seething resentment of Peter (Alex Wolff) get a rather clear explanation later in the film, but Aster wisely spends much of the time ratcheting up the tension with disturbing behavior that could be caused by the claustrophobia of the family’s otherwise ideal life.

Their evident economic security doesn’t have a clear source. There are hints that Stephen has some sort of successful endeavor that allows him to sometimes work from home. Annie’s workshop provides the only signs of actual labor, even it’s of an odd sort. Her artistry in building miniatures, a hobby of aristocrats in the eighteenth century who had the time and money to build tiny worlds they could literally manipulate, plays an increasingly malevolent role in the film. They frustrate her, become a source of tension as art dealers begin calling to express faux concern and wondering when she’ll finish her current project.

When other people impinge on the miniature world of the actual family, the results are either insignificant or diabolical. Even Annie’s efforts to attend a grief recovery support group come to nothing more than a recitation of her family history that leaves the other participants stultified. Moreover, it actually becomes the way she comes in contact with the dark things at the heart of the story. Stephen briefly tries to email someone to help Annie (an old friend? A psychiatrist? We don’t know) but becomes distracted by a message from the insurance company. Peter’s school is the only institution that makes a frequent appearance in the film, and his time in class, listening to a combination of discussions about Greek tragedy and the Great Depression, punctuates the narrative pace of the film and his own descent into the maelstrom.

I’ve kept this essay mostly spoiler-free, although there’s really little to tell about the big reveal that’s not much of a reveal. The effort to tie several supernatural threads together employs chaos rather than exposition. Serious horror fans are likely to connect the film to Rosemary’s Baby, not only because it toys with notions of insanity and the terrors of parenthood, but also because perfectly edited scenes and the morbid sense of mundane that surrounds the family tame the silly premise.

Regardless of how you think Aster handled the more traditional horror tropes in the film, most viewers will agree that the horror intertwines seamlessly with this compelling story of grief, violence, and what can only be described as hatred in a prosperous family. Annie, Stephen, Peter, and Charlie are the kind of family that thrives in America. In fact, the architects of the American Dream designed the system on behalf of families just like them.

Aster certainly did not invent the tendency to mix horror with economics, and the ideologies that hide the wounds of social class. Hidden behind Psycho (1960) is a story of a new highway making a family business go bust. Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) hints that the macabre all-male family of maniacs once made their living at the old slaughter-house, turning their homestead into an abattoir after factory farming mechanized their penchant for violence. Both Amityville Horror (1979) and Poltergeist (1982) tell tales of real estate terror: anxieties about what the family can afford and if they can have a bigger house are in the foreground before the spirits become unquiet and vengeful.

Hereditary approaches these issues from a different angle and does something similar to Get Out. Jordan Peele showed something of the horrors the privileged execute on others while Aster suggests the horrors they inflict on themselves. Behind the use of occult themes that appear in films ranging from Ty West’s House of the Devil to the Insidious series, are the horrors of privileged isolation.

Like free stuff? So do we. Here at People’s World, we believe strongly in the mission of keeping the labor and democratic movements informed so they are prepared for the struggle. But we need your help. While our content is free for readers (something we are proud of) it takes money — a lot of it — to produce and cover the stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, can keep us going. Only you can make sure we keep the news that matters free of paywalls and advertisements. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by becoming a $5 monthly sustainer today.