Recently I’ve been watching reruns of Eyes on the Prize–the old PBS documentary about the history of the civil rights movement–and a thought keeps barging in that wasn’t there when I first saw it back in 1987: Why doesn’t the Communist Party get some air time in this program? U.S.-based Communists made significant contributions to the civil rights struggle, but you wouldn’t know it from most documentaries and history books, which make room for radical political figures like, say, Malcolm X, but ignore people like William L. Patterson, Benjamin Davis, William Z. Foster, and John Gates.

Until fairly recently, I was clueless myself, and I had no idea that American Communists had been effective participants in the fight for civil rights that rapidly gained strength after World War II. Or that there was a Communist-backed group, the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), whose members made a mark through their support of black criminal defendants like Willie McGee, the Martinsville Seven, and the Trenton Six. I know more now–for the past few years, I’ve been working on a nonfiction book about the McGee case–but I can assure you that, for most people, this is history that doesn’t exist. Mention Patterson or the CRC and you’ll draw blank stares.

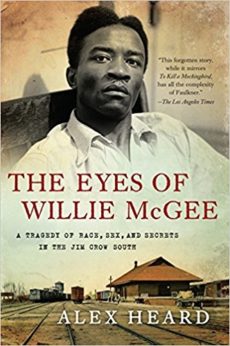

My book, The Eyes of Willie McGee, tells a true story of race, rape, and Jim Crow justice whose details will, I hope, bring new attention to a neglected part of civil rights history–the years between the end of the war and 1954, when Brown v. Board of Education, Rosa Parks, and Martin Luther King ushered in the golden-age period that is the primary focus of Eyes on the Prize.

But there was a lot going on before that, including episodes of incredible race-based violence that ought to be familiar to all Americans, but aren’t. For example, most of us know about the 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, which happened after he allegedly whistled at a white woman. Most of us don’t know about Ernest Lang and Charles Green, a pair of 14-year-olds who were brutally lynched in south Mississippi in 1942, based on a sketchy claim that they’d sexually assaulted a teenage white girl.

In those days–and well into the postwar period, which saw an eruption of lynching violence starting in 1946–mainstream news organizations still tended to bury their reports on such atrocities or ignore them altogether. As a result, the most substantial coverage usually appeared in the African-American press and The Daily Worker. In the Worker, correspondents like Harold Lightcap–a.k.a. Harry Raymond, an old-school reporter who covered everything from the Columbia, Tennessee, riots of 1946 to the Willie Earle lynching of 1947 to the McGee case–created a detailed (if sensationalized) journalistic record that, slowly but surely, began to be matched by newspapers like The New York Times and The Washington Post.

The McGee case is the best example of how the left’s journalistic witness boosted public awareness. The story began in November 1945, when McGee–a poor, semi-literate African-American truck driver from Laurel, Mississippi–was arrested and charged with raping a white housewife named Willette Hawkins. In the aftermath, he narrowly escaped getting lynched. As was common practice in Mississippi by the 1940s, he was jailed in a fortress-like lockup in Jackson, the capital city, and brought back to Laurel for trial under heavily armed guard. His first trial lasted only a day and featured court-appointed defense attorneys who barely asked any questions. McGee was hauled into court wearing a helmet, so terrified that he couldn’t or wouldn’t speak. An all-white, all-male jury found him guilty in 2 1/2 minutes and sentenced him to death.

The Daily Worker published a brief story about the trial that caught the eye of George Marshall, a white Communist who, at the time, was running a New York-based CRC precursor called the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties. Behind the scenes, Marshall arranged for a successful appeal, which was followed by a dramatic five-year period of trials, retrials, ever-growing protests, and additional courtroom fights.

It all ended grimly, with McGee’s execution in Mississippi’s “portable” electric chair on May 8, 1951. But though the fight to save McGee’s life failed, the effort to bring his story to the world worked amazingly well, thanks largely to the efforts of William Patterson–an African-American Communist who took over the CRC in 1948, after Marshall was jailed on a politically motivated Red Scare charge–and the appeals court work of a young Bella Abzug. By the end, President Harry S. Truman was receiving hundred of telegrams and letters every week, demanding that he save McGee from a sentence–death for rape–that in Mississippi was only applied to black defendants. McGee’s plight made headlines everywhere, from Memphis to Marseilles to Moscow.

In my rendition of the case–which is based on thousands of hours of archival research, interviews, and Freedom of Information Act requests–the Communist Party is not lauded at every turn. Late in the case, the CRC began publicly pushing a claim by McGee that the real story involved a love affair, not rape. He said that Mrs. Hawkins had trapped him into a long-running relationship that ended only when her husband found out, and that she “cried rape” to save herself. As it turns out, this alibi has serious holes in it. I believe the CRC knew this, but persisted with the story anyway, in a desperate attempt to save McGee’s life against unfair, unbeatable odds. Ever since then, the woman has been routinely vilified, when the real blame for McGee’s fate ought to lie with that era’s local, state, and federal courts.

In my rendition of the case–which is based on thousands of hours of archival research, interviews, and Freedom of Information Act requests–the Communist Party is not lauded at every turn. Late in the case, the CRC began publicly pushing a claim by McGee that the real story involved a love affair, not rape. He said that Mrs. Hawkins had trapped him into a long-running relationship that ended only when her husband found out, and that she “cried rape” to save herself. As it turns out, this alibi has serious holes in it. I believe the CRC knew this, but persisted with the story anyway, in a desperate attempt to save McGee’s life against unfair, unbeatable odds. Ever since then, the woman has been routinely vilified, when the real blame for McGee’s fate ought to lie with that era’s local, state, and federal courts.

On balance, though, the case is a bright spot in the history of American Communism. Back then, the party line on the right–and among “liberal” anti-Communist Democrats–was that the Communists were simply using McGee as a propaganda tool and cared nothing about him as a person. That’s not true, a fact that becomes abundantly clear when you look at the moving correspondence that flowed between McGee and CRC personnel like Patterson, Aubrey Grossman, Abraham Isserman, and Lottie Gordon. To claim otherwise denigrates the commitment of individuals who put themselves on the line for civil rights, long before it was fashionable to do so. More Americans need to know about who they were and what they did.

Alex Heard is editorial director at Outside magazine in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He has worked as an editor or writer with various publications, including Wired, The New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post Magazine, Spy, Slate, and The New Republic. His upcoming book The Eyes of Willie McGee will be release in May 2010. Go to the author’s website, The Eyes of Willie McGee, for updates on the book or to have a conversation with the author.

Photo: Image from the Daily Worker archives at NYU’s Tamiment Library.