Reconstruction, America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877, by Eric Foner, published in 1988, is a delightful read, all 619 pages. It’s not a new book, but there is renewed interest in Reconstruction by the movement around Black Lives Matter and others. And Foner shares with the reader many samples of what people were saying or writing during Reconstruction, giving us greater insight into what was going on at the time.

Reconstruction, America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877, by Eric Foner, published in 1988, is a delightful read, all 619 pages. It’s not a new book, but there is renewed interest in Reconstruction by the movement around Black Lives Matter and others. And Foner shares with the reader many samples of what people were saying or writing during Reconstruction, giving us greater insight into what was going on at the time.

He dates the beginning of Reconstruction, the re-making of the Confederate South, to Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. That got my attention because I had thought Reconstruction began after the end of the Civil War in 1865. But I read on and soon saw the author’s logic. Emancipation was a revolutionary change, an essential step to taking away power from the rebel slaveowners. Emancipation was also necessary for the North to win the Civil War, a war that they had been losing up to 1863.

The Emancipation Proclamation made official what was already happening on the ground. By 1863, a large number of enslaved people had freed themselves and run away to join the Union Army. Of those who remained on the plantations, slave owners complained that many were refusing to work. Here, Foner takes his inspiration from W. E. B. DuBois’s Black Reconstruction, still the classic work on this critical period of history.

DuBois also wrote that the Emancipation of those enslaved in Confederate states was a step needed by the North to win the war. In the chapter of Black Reconstruction titled “The Propaganda of History,” DuBois questions the ways in which Reconstruction was being taught in our schools.

“How the facts of American history have in the last half-century been falsified because the nation was ashamed. The South was ashamed because it fought to perpetuate human slavery. The North was ashamed because it had to call in the black men to save the Union, abolish slavery, and establish democracy. What are American children taught today about Reconstruction?…that Negroes were the only people to achieve emancipation with no effort on their part. That Reconstruction was a disgraceful attempt to subject white people to ignorant Negro rule ….”

To DuBois’s devastating exposé of the lies in the history textbooks, Foner adds, on p. 609: “This rewriting of history was accorded scholarly legitimacy—to its everlasting shame—by the nation’s fraternity of professional historians.” This reviewer can affirm that a falsified version of history is what I read in my school textbooks. And I didn’t know any better until I read DuBois’s brilliant study of Black Reconstruction.

The Reconstruction Revolution

On Jan. 31, 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery throughout the nation, was sent to the states for ratification. To complete the revolution, once the abolition of slavery was nationwide, two additional steps were required. As Frederick Douglass warned, “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot.” Blacks were the majority in several Confederate states and had won political power for the few years that Black men had the ballot. By the time Reconstruction ended, Black men were again denied the ballot by terroristic violence and passage of “Black Code” laws.

Without the ballot, the freedmen had no access to political power and the revolution against slavery remained unfinished. The other key issue was ownership of the plantations that had been forfeited when their owners seceded from the United States. Should that land be democratically divided into family-sized farms and given to the freedmen who had long cultivated the land without pay, enriching the slaveholders? Or should the traitors who seceded be forgiven, and should they get the plantations back to exploit Black labor again?

Gen. Sherman, in his “Special Field Order 15,” provided for the division of land in the Sea Islands and a 30-mile strip of land along the Charleston rice coast. Much of this land had been abandoned, and the rice irrigation works stood in ruins. The land was to be divided into 40-acre family farms and distributed among the freedmen families. Sherman added that the army would loan the freedmen mules. Foner credits Gen. Sherman (pp. 70-1) for the origin of the demand, “Forty Acres and a Mule.”

This was a model that could have been widely applied and would have created a huge economic base for democracy in the South. While 14,000 Black families in South Carolina did get land, that was only 1/7 the number of freedmen in the state. But it was not what Northern bankers or manufacturers wanted. And it was certainly not what the former slave-owning and plantation-owning Southern ruling class wanted. Nor was the division of plantations into 40-acre farms for freedmen what Presidents Lincoln, Johnson, Grant, or Hayes wanted.

Reconstructing Southern state governments

On Dec. 8, 1863, less than six months after the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction. All that former plantation owners had to do was to pledge future loyalty to the Union and accept the abolition of slavery. Then the secessionists’ right to vote would be restored and their forfeited property would be returned.

Excused by some as a wartime measure to split the ranks of the Confederacy, Lincoln’s offer still showed a readiness to give the confiscated plantations to the former slaveowners. Some thousands of higher-ranking Confederate officers were excluded from Lincoln’s offer, but his successor, Andrew Johnson later pardoned some 7,000 of them.

Tragically, Lincoln’s assassination put the presidency and Reconstruction in the hands of Vice President Johnson. Johnson had been the only Southern U.S. Senator who opposed secession. But he was never opposed to slavery, and he strongly opposed Black suffrage. The new Southern state governments that Johnson set up enacted Black Codes and used anti-vagrancy laws to force the freedmen back to the cotton and rice plantations. The title of Foner’s chapter on Reconstruction as directed by Johnson sums it up: “The Failure of Presidential Reconstruction.”

Radical Reconstruction—Black Reconstruction

Congress then took over leadership of Reconstruction policy, a period known as “Radical Reconstruction.” Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act on March 2, 1967, over Johnson’s veto. Before a Confederate state could return to the Union, they had to accept not only the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery nationally but the 14th Amendment as well, which guaranteed birthright citizenship and equal rights under the law.

The new Reconstruction state governments, with substantial Black participation, extended the ballot to Black men. By July 6, 1869, Congress approved the 15th Amendment that extended Black male suffrage rights nationally.

In all of these history-making events, the Black population was far from passive. At some length, this book documents the massive political activity of the freedmen. That political activity was ongoing and was ended only through the terror and violence of the Ku Klux Klan, given a free hand by the withdrawal of the U.S. Army from the South. Much of the leadership of Black organizations came from the Black men who were free before the war.

But their power came from freedmen’s massive, active participation. The freedmen’s and freedwomen’s political interest was so intense that they took time off from work to attend political meetings. Employers complained that nobody showed up to work when Black political meetings took place.

What about the women?

Foner writes that under slavery, both enslaved men and women were deprived of all rights. Even the right of enslaved families to be a family was not recognized. Indeed, the first effort by the new freedmen and freedwomen was to look for family members who had been sold away. (What a book of experiences that would be! Makes me cry just to think of it.) Further, Foner states, on p. 87, that the patriarchal family model was first imposed by the Freedmen’s Bureau, requiring the man of the family to sign annual contracts binding the entire family to work on a plantation, young children not excluded.

The very first national women’s rights meeting, at Seneca Falls, N.Y., in 1848, was led by two abolitionists, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Frederick Douglass, in a historic speech at the meeting, gave a speech in favor of women’s suffrage that some attendees then thought was too radical. This promising alliance of the Black and women’s rights movements was shattered during the fight to pass the 15th Amendment.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, with Douglass’s support, had fought to include women’s suffrage in the 15th Amendment. In February 1869, when the 15th amendment passed Congress giving the ballot to Black men but not to women, Stanton and other women suffragists opposed the amendment altogether and split the Equal Rights Association in two. Foner reports (p. 448), Stanton “increasingly voiced racist and elitist arguments for rejecting the enfranchisement of black males.” That shameful turn had consequences that are still being felt today.

Violence ends Radical Reconstruction

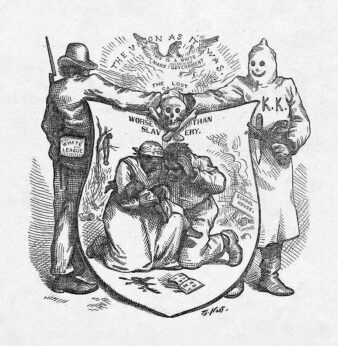

The slave states had always been highly militarized and ruled by force. The violence used against Radical Reconstruction was extreme. Foner details (pp. 425-44) the rise and spread of the Ku Klux Klan, Knights of the White Camelia, and the White Brotherhood.

Black legislators were terrorized, and many were murdered. Other targets of the white terrorists were teachers and literate Black people. After burning a Black teacher’s library, terrorists said, “They would just dare any other n______ to have a book in his house.” Massacre after massacre took place, with 280 Black people murdered in Colfax, La., alone. With a few honorable exceptions, appeals to governors to call out the militia for protection of Black citizens or to the U.S. Army were ignored. But when it came to stealing land from Native Americans or protecting railroad profits, the U.S. Army was right on the job.

In 1877, as the last Reconstruction state governments were being toppled, the Army pursued the Nez Percé Indians to remove them from Oregon’s Wallowa Valley. The Nez Percé put up a brilliant defense but were forced to surrender. The irony of this land grab was that the Army commander, O. O. Howard, was a former Freedmen’s Bureau chief. Also, some of the Army troops that pursued the Nez Percé were sent in from the South. Southern troops were available since they were no longer protecting Reconstruction or stopping terror against Black citizens.

Three months after the end of Reconstruction and the restoration of white supremacy in the South, the Great Strike of 1877 started in Martinsville, Va., to protest the second wage cut in a year by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. It soon spread along railroad lines to cover the country, except New England and the deep South. Some 40,000 coal miners joined, and there were general strikes in Chicago and St. Louis. Demands centered around the 8-hour day, restoration of the pay cuts, and an end to child labor.

The strikes were marked by cooperation between skilled and unskilled and between Black and white workers. Republican President Hayes sent troops to cities—from Buffalo to St. Louis—where they acted “as strikebreakers, opening up railroad lines, protecting non-striking workers, and preventing union meetings.” Hayes wrote in his diary, “The strikers have been put down by force.” As Foner concludes (p. 585), “All in all, the events of 1877 confirm the growing conservatism of the Republican Party.”

Lasting contributions of Reconstruction

The various Reconstruction state governments passed a lot of good legislation. The question, of course, was one of enforcement. One law that could not be wiped out, and that few recognize as a Reconstruction achievement, was public education in the South. The importance that the freed men and women gave to establishing and funding public education was fundamental. Their insistence that their children attend school was a major reason that freedmen did not like the contract system of plantation labor that many freedmen were forced to sign.

These contracts bound all members of the family, including wives and children, to work for the plantation owner. By the early 1870s, sharecropping became the dominant form of plantation labor. Freedmen preferred sharecropping to contract labor because the children could go to school. But a new landlord-merchant class developed in the South, and debt peonage expanded.

All working people of the South, white as well as Black, suffered economically because the revolution in process during Reconstruction was reversed. The plantation-based economy was so inefficient that in the years 1872-77, per capita income in the South was only 1/3 as high as the rest of the United States. Even in the progressive era of the 1930s New Deal, the WPA—the government jobs program—in the South had a lower wage scale than in the rest of the country.

In fact, the ending of Reconstruction left the plantation-owning class with more political power than they had before the Civil War. Although terror, poll taxes, “literacy” tests, and more deprived Black Americans of the vote, the South gained seats in Congress because Black persons were fully counted, instead of only as 3/5 of a person.

The Civil Rights movements of the 1930s and the 1960s-70s made further strides towards winning the right to vote. That fight continues with the rise of Black Lives Matter and the many labor and community organizations fighting for the right to vote. Eric Foner’s book makes an important contribution to that fight.

Comments