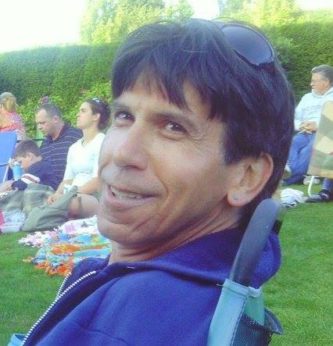

GROVE, Okla.—“Our existence is the resistance,” Jim Wikel, Seneca-Cayuga tribal member here told People’s World in an exclusive interview. Wikel was speaking of Native environmental issues at the 19th National Environmental Conference at Tar Creek, in late September, in Miami, Oklahoma. Miami is northeast of Tulsa near the Kansas-Missouri border. It has been the home site for the conference the past 19 years, and this year’s theme was “Climate of Denial.”

Tar Creek is a United States Superfund site where years of lead and zinc mining produced uninhabitable conditions. It sits on the traditional lands of the Quapaw Nation. After suffering for years from contaminated water, lead poisoning of children, and sudden sinkholes, the town of Picher, Oklahoma was completely evacuated on orders from the Environmental Protection Agency. It was declared the worst site in EPA history. Picher is located at the northeast border of Oklahoma and Kansas on Highway 69 and is today a ghost town, permanently quarantined.

Decades of racist policies on the part of the government and the mining companies which leased their land left the people of the Quapaw Nation exposed to acid mine water, chemical poisoning, and underground sinkholes that threatened to swallow their homes. The 2009 documentary Tar Creek by Matt Myers brought their story to a wider audience.

It was in this context that the attendees of the Tar Creek conference met.

Destroying the land, erasing culture

The story of how Wikel came to be a participant at the Tar Creek gathering is a unique one. In his early life, Wikel had no regard for the environment, but like an Indian medicine wheel, his life has now evolved full circle.

“I was involved in the Standing Rock pipeline protest last year,” Wikel told People’s World. Standing Rock in North Dakota was the site of the water protectors’ protest last year. “In Oklahoma, I’ve been involved with Oka Lawa Camp which is now Good Hearted People Camp,” Wikel said.

The camp is located in Harrah, 22 miles due east of Oklahoma City. “The conference wanted me to speak on pipelines,” he said, “but it is much deeper than that.” A previous speaker had assailed the government use of eminent domain to steal land, and said that not stealing land would be the American way. Wikel disagreed: Looking at history, stealing land, he said, actually is the “true” American way.

“The American people from day one have taken land and exploited the natural resources for profit since they set foot on this continent,” Wikel continued. “Indigenous rights and environmental rights are the same if you ask me.”

“My mother, from Grove, Oklahoma, was Seneca-Cayuga, and my father was non-native. However, they moved to Washington state where I was born. I knew I was Indian but we never talked about it.”

Brutal beatings and the forced loss of culture for his maternal grandparents at the hands of government boarding schools is why his family didn’t discuss their heritage when Wikel was growing up.

The goal of Indian boarding schools was to “assimilate” Native Americans into “white” culture. It was a plan by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the agency which had governmental oversight of the tribes. The culturally abusive tactics used in the schools were part of a bigger “colonization” strategy.

Wikel described how his grandfather was sent off to the Seneca Boarding School in Wyandotte, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) in 1905 when he was only five years old. He was held at the school until he was 14. “Afterwards, he never spoke the language or went to ceremony again, and he never taught any of that to his kids,” Wikel said. “He drank himself to death when he was 43 years old.”

“My mother was in Chilocco Indian School in Newkirk, Oklahoma, north of Oklahoma City on the Kansas border, when she 16 and 17. She had experiences there that I never knew about until about six years ago.” Wikel said his mother had become pregnant there with his older half-sister. When she was born, the baby was sold on the human trafficking market to a white family.

“This trauma has carried through my family. Last year, at the age of 56, during our Green Corn Ceremony, I was given my Seneca-Cayuga name. I am the first one in my family since my grandfather to have a traditional Indian name.”

“I truly assumed my true identity, when I was given my name. Two months later, I went to Standing Rock Reservation.”

From clear-cut logger to water protector

During Wikel’s youth, he had run-ins with the law and dealt with addiction issues. “My mom and dad split up when I was thirteen. My dad stayed in Washington while my mom, my two younger sisters, and I stayed in Oklahoma. Not coincidentally, this was when I began to use drugs and drink alcohol. When I was 19, I went to Washington to live with my dad,” Wikel said.

Wikel said after he moved to Washington he worked in the timber industry, decimating natural resources. “This was during the 1980s, which were the last years of the unrestricted logging of the old growth forests of the Pacific Northwest. During these years, I was drinking heavily as well.

“The type of logging I was involved in was clear-cut logging, usually on steep slopes. We decimated whole ecosystems that will never again be seen in our lifetimes. We destroyed groves of huge old cedar trees,” Wikel said.

“These groves were sacred to the tribes of the Northwest. In the late 1980s the so-called spotted owl controversy began to make the news. Environmentalists were calling for the curtailing of harvesting old-growth timber. Massive rallies were held in the timber towns of the Pacific Northwest. A popular bumper sticker that was seen on the pickup trucks of loggers throughout the Northwest read, “Wipe your ass with a spotted owl.”

Wikel recalled, “A radical environmental group called Earth First! began to protest logging operations. Members of the group would chain themselves to logging equipment, block logging roads, plant railroad spikes in trees, and even lived in the forest canopy in an effort to stop logging. We made fun of them and called them dirty hippies.”

Wikel remembered when on group of protesters came to his worksite. “One woman looked at what we were doing and wept. I could not understand why she was weeping. Today, I understand why she was weeping.

“Cedar was like buffalo to Native Americans in this area,” Wikel explained. “They made clothing, built canoes, and created houses out of cedar.”

“It was a protester that made me think about what I was doing,” he said. “I was stunned that she was crying,” he remembered, but that moment eventually evolved into his own awakening.

“Getting sober, getting in touch with who I was as an Indian, that is when I awoke. I think that my shift of consciousness began when I got sober in 1991. That was when I began my journey to myself.”

Wikel said that about a decade ago, during a sweat lodge ceremony, he felt called to move back home to Oklahoma. It was two years ago that he finally moved to Seneca-Cayuga Nation headquarters in Grove.

“I have been learning our language and participating in our ceremonies, which are all about being grateful to the Earth and to the Creation for our sustenance. Last year, at the age of 57, I received my Indian name, which further helped to ground me in my identity as Ogwehoweh, as one of The Original Beings,” Wikel said.

In his middle age, Wikel said it was the youth which inspired him to become an activist. “It was the young people of Standing Rock that first went to Washington. The young people did that.” Youth from the Standing Rock Reservation were the first to speak to Congress about protecting the water.

“It was the young Chahta [Choctaw] youth that started Oka Lawa, which became the Good Hearted People Camp,” Wikel explained.

Good Hearted People Camp is a symbiotic community for water protectors and land protectors, a place, according to Wikel, to de-colonize and indigenize. “Even some of the younger ones desire to build and live there.”

Wikel was right that it goes much deeper than simply speaking up about pipelines. He was right: “Our existence is our resistance.”

“I think that the more I know myself as Ogwehoweh, as a Human Being, the more I am connected to Mother Earth and the more I am connected, the more I want to protect our Mother for our future generations.”