CULVER CITY, Calif.—If you have received opinions, best leave them at the door when you visit the Wende Museum of the Cold War here, a few blocks west of the downtown area in a building that once served as a Cold War-era armory. The last time I reported on the Wende was to survey some of the “utopian” thinking about “alternative realities” that has informed many left movements—anarchism, socialism, communism—and some right-wing movements as well.

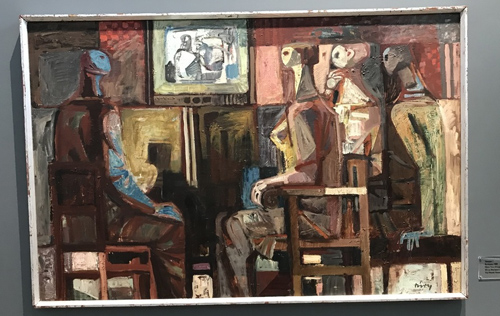

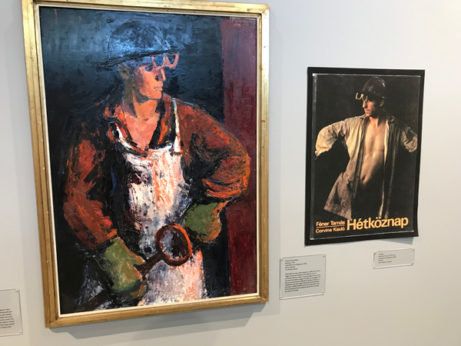

The current exhibitions in this open, welcoming contemporary space are Promote, Tolerate, Ban: Art and Culture in Cold War Hungary (which is a collaborative initiative of the Wende Museum, and the Getty Research Institute) and Socialist Flower Power: Soviet Hippie Culture. There aren’t many places in the world where the Cold War culture of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union are taken as seriously as here. I won’t say “objectively” because that is a highly elusive term, although in the same breath I would observe that the Wende tends to emphasize a darker, more authoritarian interpretation of “actually existing socialism” than I might. For example, I would balance some of the ugly against what I consider a fair amount of good—recovery after World War II, scientific and cultural achievements, universal education and healthcare, opposition to Western imperialism, support for decolonization and the anti-apartheid movement, and so forth. But whatever: Definitive conclusions are left to the viewer’s discretion.

The ideological questions of course come into play considering Hungary post-1956. What was the nature of the revolution that year against the standing Soviet-installed government? Was it a “counter-revolution” funded by the West and aimed at restoring capitalism, as orthodox communists were taught and believed? Or was it a spontaneous breakout of anti-Stalinist reformers who knew that Hungary deserved a more liberal version of socialism than what Uncle Joe had imposed on them, something of the “socialism with a human face” idea that re-emerged in Prague in 1968, and which met with a similar repressive response from Moscow? And if the appearance of Soviet tanks on the streets of Budapest in 1956 and Prague in 1968 appeared like a shockingly crude means of asserting Soviet dominion within its sphere of influence, could such moves be understood in the end as part of the larger project to keep the socialist project going and prevent imperialism from destroying this precious idea? Western military intervention, after all, was no prettier, and resulted in far more loss of life.

These are among the questions I bring to the Wende, but back to the subject at hand: Promote, Tolerate, Ban makes the case that once Imre Nagy’s rebel government was suppressed—the Soviet tanks surrounded the Parliament in Budapest on November 4, 1956—and the succeeding János Kádár government took over (remaining in power until his retirement in 1988), Hungary did not remain static. After all, this is what history is about, tracing changes, trends, movements.

The title of the exhibition derives from an internal document that laid out the general plan for handling dissidents. First promote fresh ideas, new currents within socialism, maybe incorporate what might be positive and useful. Then, if the artists get too rambunctious, tolerate up to a point to let them ventilate a bit, and see where their notions are headed before they get out of hand. Finally, if certain ideas are gaining too much traction and threaten to delegitimize the government, ban them—this may be unpopular but self-preservation is at stake. (I am extrapolating on these terms in my own words.)

After 1956 the government took stock of the pent-up desire for more consumer goods and more cultural freedom. Television came in and news assumed an immediacy print could not communicate. Advertising started to reflect Western values, pop culture. For example, a poster promoting vacations at Hungary’s famous resorts on Lake Balaton, a destination for workers from all over the Eastern Bloc, featured a modern high-rise hotel in the background and a shapely, bikini-clad woman occupying the foreground. Such exposure of flesh—and such invitation to fantasy—would have been unthinkable before. The “deal” Kádár struck with the Soviets was essentially 100 percent loyalty on foreign affairs in exchange for domestic autonomy.

A stern crackdown in Hungary came after the Prague Spring of 1968; again, authorities worried about too much openness of expression. Later iterations of independent thought came about through Hungarian samizdat, underground publications such as an unofficial translation of Orwell’s Animal Farm, or mail art which encouraged artists to exchange visual ideas across political borders. Beginning with the rise of photocopy machines, the spread of alternative ideas became that much easier; our guide told us that during that period the Hungarian-born magnate George Soros was one of those who funneled money and copy machines into the country. Perhaps the government had a point when it accused the West of trying to undermine socialism! Even the circulation of private albums of photos and journals could be interpreted as a means of wresting some personal time and agency away from the almost entirely socially managed space of approved existence.

Repression came in waves, but independent thinkers survived during the interstices. Over time, Hungary gradually became one of the most liberal and tolerant places in Eastern Europe, comparable in some ways to East Germany, which had its own reasons to be relatively liberal, being so close to its competition in the West. By the 1980s, Hungarians had access to Coca-Cola, which to them symbolized an opening to the best the world had to offer. Sándor Pinczhelyi’s painting Star Coca-Cola from 1988 may be soaked in ironic meaning, but surely the intent is to imply that the two systems of capitalism and socialism are capable of cooperation and to an extent, integration. What essential contradiction is there if people want Coca-Cola under socialism? In the end, by the time the Soviet Bloc came crashing down, it was, after all, the Hungarians who first cracked the Wall by opening its border to Austria.

As part of the programming concurrent with the exhibition the Wende showed A Bibó Reader, Péter Forgács’s biopic in experimental form about István Bibó (1911-1979), lawyer, historian, intellectual, who for one day, during the 1956 Revolution, acted as the Minister of State for the Hungarian national government. When the Soviets invaded, he was the last Minister left at his post in the Parliament building. Rather than evacuate, he stayed inside and wrote his famous proclamation “For Freedom and Truth” as he awaited arrest.

Imre Nagy, head of the Hungarian reform government, was executed. Bibó was not arrested until May 23, 1957, and was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1958. He was released in the 1963 amnesty, but essentially lived under house arrest for the rest of his life.

The film surveys many of Bibó’s major historical and philosophical writings, in which he analyzes the peculiar form of romantic patriotism a number of Eastern European societies adopted in the wake of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Though apparently not a Marxist as such, he showed a sophisticated grasp of class issues, pointing out how the old aristocracy put the brakes on truly democratic prospects at every turn. It was they who put an end to the Hungarian Revolution in the 1918-1920 period—which they accused of being a Jewish conspiracy against God—dreaming of restoring their former power. Not surprisingly in 1956 it was easy for the orthodox Communists to jump to the earlier analogy and see the reform movement as necessarily an irredentist putsch.

Although Forgács has a “reader” reciting critical passages from Bibó’s essays (often against footage of Hungarian daily life that seemingly has little to do with the words), he was able to obtain recordings of Bibó’s own voice in a series of reflections on the meaning of Christ, the persecution of the Jews of Europe, the futility of anger and retaliation, and the consummate importance of personal responsibility.

In the immediate post-Soviet period, Bibó became a Hungarian cultural hero. To be a democrat, Bibó asserted, was “not to be afraid, of opinions, races, languages, revolutions, scorn, propaganda, imaginary threats.” But as the government turned hard right under Viktor Orbán, Bibó’s broad humanism has again gone out of favor. The exhibition has footage of the young Orbán in the waning days of socialism, demanding a rightful reburial and recognition of Imre Nagy.

Soviet hippies

The Soviet press took note of the 1969 Woodstock Music & Art Fair, observing gleefully how much it proved the alienation and anti-capitalist sentiments of youth within the heart of their global rival. Little could they imagine that young people under socialism might be feeling the same alienation against a regime that simply could not keep up with their aspirations to live more freely, travel, look different, listen to rock music, draw surrealist images, grow out their hair, enjoy free love, and get high.

In retrospect, while capitalism had the capacity to adapt to and absorb most of the above, the Soviet system viewed all of it as an existential threat to its hegemony. With every attempt to suppress, the alternative resistance simply grew angrier and more resistant. Even punishment for wearing homemade clothing and long hair, by being placed in a psychiatric institution, had its upside: You’d no longer be eligible for military service.

The hippies of Moscow planned a demonstration against the Vietnam War on June 1, 1971, and got official permission for it—a march starting from Moscow State University heading toward the American embassy. As one participant put it at the time, “We didn’t want to stand on the sidelines and look at what was going on as bystanders. Well, now everyone will know that long-haired hippies can do something worthy of human beings too!”

But the authorities duped them: When the hippies assembled, police moved in and arrested them all, over 600 by some estimates. This event became emblematic of one of the great failures of Soviet-style socialism, the discouragement of the autonomous civic sector. Perhaps better known are the 1974 dispersal by bulldozer of open-air art exhibitions by non-officially recognized artists, or the 1975 censorship and seizure of alternative art by the hippie collective Volosy (Hair), both of which received enormous critical attention in the Western media.

In the Soviet view, hippies were essentially a law-and-order problem. People with long hair would be stopped in the street, taken to police stations, and registered as anti-social elements. There was, of course, some truth to this. As Natasha Kzantseva wrote about meeting some of them, “Sveta told me what hippies are and that it’s not just long hair and some special trousers; that it’s ideology, ideological protest against routines, protest against dullness, protest against lies, protest against grayness, protest against cruelty, against any kind of war.”

Perhaps it was simply the Zeitgeist of the 1970s and ’80s: Young people wanted pleasure, sometimes of the ecstatic kind obtained by ingestion, by wild dance and loud music, and were not content to serve as obedient builders of socialism rewarded by the annual union members’ family vacation in Sochi. They established their own standards of decorum, they traveled “abroad”—to the Baltic republics for a taste of Western style, to Central Asia for exoticism and locally produced drugs, to the Crimea and the Caucasus for sun. They decorated their apartments with murals, they made journals and books, designed their own clothes, and exchanged addresses where they’d be warmly welcomed wherever they wandered.

Above all, the hippies resisted stagnation, that deadening sense that nothing was ever going to improve, attitudes were never going to change, and life was never going to be fun or meaningful. Perhaps they resembled the first generation of radical Bolsheviks in the 1920s more than the nomenklatura—the bureaucracy—could ever admit.

The Soviet Union needed to adapt to the changing times with far greater agility than it proved capable of. By the time perestroika came in the late 1980s, it may have already been too late.

Visitors to the Wende will see photos, journals, film footage, art, clothing, and can pick up a very informative 28-page illustrated booklet on Socialist Flower Power: Soviet Hippie Culture. With all my but-what-about reservations—what about all the things the USSR did do successfully—the Wende draws from its extensive collections and lays out a compelling case for looking at the socialist reality with open eyes. As I say, if you come here, leave your preconceptions home.

The Wende Museum is open Fri., 10 am to 9 pm, and Sat. and Sun., 10 am to 5 pm. Weds. and Thurs. are open for school tours only by appointment. Public curator-led tours are offered at 12 pm and 1 pm on Sun., Aug. 19, and every Fri. at 11 am and 2 pm. The Wende Museum is located at 10808 Culver Blvd., Culver City 90230. Their phone number is 310-216-1600. Admission is free. The current exhibitions run through Sun., Aug. 26.

In conjunction with Promote, Tolerate, Ban, the Wende and The Getty Center sponsor a screening and discussion entitled “Looking into the Camera: Amateur Films, Surveillance, and Experimental Video Art in Cold War Hungary,” on Sat., July 21 at 6:30 pm at The Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Dr., Los Angeles 90049. For further information, see the Wende website here.

Like free stuff? So do we. Here at People’s World, we believe strongly in the mission of keeping the labor and democratic movements informed so they are prepared for the struggle. But we need your help. While our content is free for readers (something we are proud of) it takes money — a lot of it — to produce and cover the stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, can keep us going. Only you can make sure we keep the news that matters free of paywalls and advertisements. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by becoming a $5 monthly sustainer today.