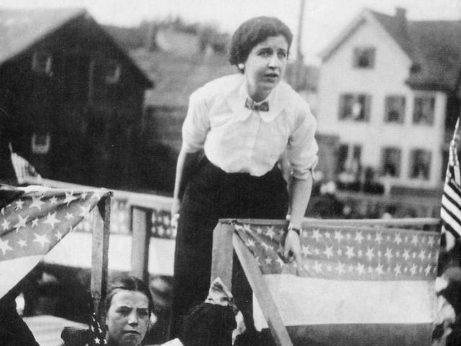

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890-1964), known as “The Rebel Girl,” was one of the premier labor activists and leaders of the struggle for women’s equality in the 20th century. She was an organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World, a founding member of the ACLU, and later in life the Chairperson of the Communist Party USA. In this article, originally printed under the headline “For the Rights of Women,” in the Daily Worker on March 11, 1954, Flynn discusses the U.S. origins of International Women’s Day. She says that while the women’s suffrage movement is rightly regarded as a milestone in the fight for equality, the concerns of working women extended far beyond the ballot box. The determination of 20,000 young and diverse working women in the textile industry who went on strike and led the first “American Women’s Day” in 1909 started the IWD tradition. The Rebel Girl talks about those strikers in this article and calls on readers to correct the problem that existed of too many American workers not having knowledge of their own past victories.

At the turn of the last century, thousands of thoughtful American women were deeply stirred at the denial of votes to women. Some protested politely in white-gloved Carnegie Hall gatherings. Some spoke on the street corners and were heckled: “Go home and wash your dishes!” Or asked, regardless of age, “Who’s taking care of your children?”

One woman was queried, “How would you like to be a man?” She replied tersely, “I wouldn’t. How would you?”

Some picketed the White House and burned President Wilson’s fine phrases about democracy in a pot outside his door. They were arrested and sent to a horrible workhouse which they exposed to the world.

Maude Malone, a valiant fighter (who at her death was librarian of this newspaper) marched on Broadway when I was a young girl, bearing placards, “Votes for Women” front and back like a sandwich man, and lost her job in a library.

Various reasons moved different groups. There were the staunch veterans, who had been ridiculed, ostracized, disowned by families, and arrested for attempting to vote.

There were rich women who represented the cause “Taxation with Representation.” Professional women resented the obstacles placed in their way in schools and colleges. Working women wanted “Equal pay for equal work,” and laws on hours, safety, child labor, and sanitary regulations.

All were convinced that votes would be a powerful weapon to remedy their grievances.

They paraded, held meetings in churches, published papers, pamphlets, and leaflets, and lobbied in state legislatures and in Congress. There was every type of organization. They followed candidates around, forcing them to take a stand, as Mother Bloor described her suffrage work in Ohio.

More and more women resented their second-class citizenship, their lack of control over their lives, their children, their property, and their wages. A militant movement grew to enormous proportions, which finally won “Votes for Women” in 1920, when the 19th Amendment, known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, was passed.

The leaders of the suffrage movement were predominantly native-born, articulate, and aggressive. But working women were not adequately represented, and their needs were not sufficiently expressed in the official suffrage movement. In fact, there was already evident in some quarters opposition to “protective legislation” which actually restricted the rights of mothers and working women in the name of “equality.”

But activism began to develop among working women as early as 1908, not least of which was the East Side demonstration of foreign-born, unorganized working women in New York’s needle trades sweatshops of the day. It was organized by the Women’s Committee of the Socialist Party, headed by Margaret Sanger. She was a nurse and later devoted her life to the advocacy of birth control.

By the next year, 1909, there were 20,000 of these women workers engaged in a great strike of waistmakers on New York’s East Side. It was called “the girls’ strike.” Eighty percent of the workers were women, the majority between 17 and 25. They worked 56 hours a week in dirty firetrap buildings, sped up in the season, and put out of work completely in slack time.

The struggle started in two shops and spread after a meeting in Cooper Union at which a girl striker, Clara Lemlich, said, “I am tired of listening to speakers. I make the motion that a general strike be declared.” She is among those who should be honored as a founder of unionism in the United States.

Because of its working-class origin and these simultaneous struggles, Clara Zetkin, leading German woman Socialist, welcomed American Women’s Day. She had urged a lengthy struggle in Germany to include women’s suffrage in the demands of the Social Democratic Party. There was opposition from some of her male comrades at the time because “women will vote reactionary.” They said that “if you give women the vote, they’ll vote the way the priests say.”

At the Congress of the Socialist International in 1910—with the support from August Bebel of Germany, Vladimir Lenin from Russia, and Big Bill Haywood and others from the U.S.A.—Zetkin’s proposal that March 8 be designated International Women’s Day was accepted unanimously.

It was dedicated to the struggle for the full rights of women. It has spread around the world and is celebrated today in many lands—China, the Soviet Union, the Eastern democracies, France, Italy, and England particularly.

Yet here in its birthplace, it has been allowed to dwindle away so that many here have forgotten or never know its American origin and significance. It is up to us to change that.