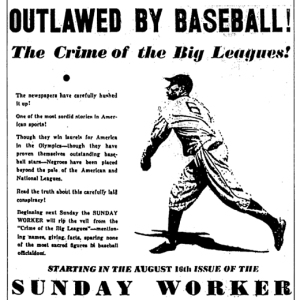

The Daily Worker, predecessor of today’s People’s World, and its Sports Editor Lester Rodney were among the few voices in the 1930s and ’40s tackling the issue of segregation in major league baseball—what the newspaper called “Jim Crow Baseball.” Major newspapers overlooked the issue and legitimized the unwritten rule of racial separation. Team managers, club owners, and league presidents dodged hardball questions and gave scripted answers when questioned. The Daily Worker’s coverage and campaign to desegregate baseball lasted from 1936 until April 15, 1947. That was the day Jackie Robinson, #42, walked onto the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers. The article below originally appeared in Rodney’s Daily Worker column, “On the Scoreboard.”

Here it is Opening Day if it doesn’t rain and time for a traditional column on same.

But it’s hard this opening day to write straight baseball and not stop to mention the wonderful fact of Jackie Robinson.

You tell yourself it shouldn’t BE especially wonderful in America, no more wonderful for instance than Negro soldiers being with us on the way oversees through submarine infested waters in 1943. And that never seemed “wonderful,” just sensible, necessary, and right.

It’s quite possible to be stupid about something like this. After chatting with Jackie on the field the first day he was in a Dodger uniform and becoming overwhelmed with the feeling of pressure and tension thrown fully upon his broad shoulders by the spotlight of publicity, the scrambling photographers oblivious of all else, even the kids pushing for autographs at his every move, it took no remarkable perception to know that beneath Jackie’s smile was at least a little wish to be let alone and treated just like any other rookie, on his merit. And I decided then and there to start writing less about him in my Brooklyn stories.

But that didn’t seem quite right. It didn’t square with the inescapable feeling that the readers WANTED to know about him. A conflict.

Then up in the press box Saturday, his second day in uniform, when the special warm applause continued to roll down from the Ebbets Field stands every time he went to bat though he had been doing nothing spectacular, another writer sitting near me, a right enough guy, said, “I wish they would stop that already and just treat him as another ball player.” I suddenly knew he was wrong. The conflict evaporated.

For like it or not, Jackie Robinson was not “just another ball player” down there. Not yet! The continuing cheers from the 25,000 strong cross-section crowd was actually expressing America’s great inherent sense of sportsmanship, equality, and Bill of Rights democracy, if you will, was insisting on expressing it fully when given the dramatic concentrated chance to do so.

The repetition and re-emphasis that worried my well-meaning friend carried with it the awareness that Negro Americans hadn’t been allowed to play down there before, that everything WASN’T smooth and equal for either the Negro people or Jackie Robinson. Consciously or not, it carried an answer to Bilbo and Rankin and their northern counterparts; it carried decent human feeling down to Robinson on the field and a message to every magnate in the big leagues.

In the surprising—yes surprising to me too—depths of the cheers for Robinson was the real democracy of the vast majority of our people, a democracy sometimes blurred, stultified, confused, rationalized, and diverted, but still in there waiting for a chance to come through.

And here it was!

You can’t ask people to measure, to control their democracy. Cheer on for a while, you people of Brooklyn! Cheer on, democracy!

And when the Dodgers go to Boston and Philadelphia and Cincinnati and Chicago and Pittsburgh and St. Louis, there’ll be special cheers when Jackie Robinson steps out of the visiting dugout.

And maybe we were wrong about Jackie’s own feelings. The cheers and commotion add to the pressure he’s under, sure, but he knew what he was doing when he started fighting for a big league job, when he became the first, the forerunner, knowing he had to be better than just good enough.

The cheers may make it a little tougher on Robinson, the athlete, in a way. But the cheers are saying something, something that will make it easier for Negro players to come, for the day when there’ll be no special pressure upon an American ballplayer whose skin happens to be dark.

I guess Jackie must know that.