Terms like “silent majority” or the “sleeping masses” are still used today but they feel dated, often leaving one wondering if they’re nothing more than a bad joke taken seriously in order to be polite. A politician or news anchor says something of a “silent majority” in order to (hopefully) activate these unnoticeable groups—these supposed waves of influence—and we are all meant to hold in our laughter while imagining millions of underground cells of voters waiting on the call to do the thing they do every year but with extra purpose.

Maybe the image is no longer innocently comedic. Perhaps there is something cynical in it. After all, is it possible to believe anymore that people are so completely unaware of what is happening in the world that, somehow, both the political right and left have equal claim to this so-called majority based on how they describe their (in)activity?

Perhaps even more depressing is the fact that the world’s most traumatic realities are considered “outside” the world of politics: Depending on which side one falls on, problems like climate change, global pandemics, and homelessness are either curable by love and hard work or incurable because of the missed opportunity for love and hard work. Perhaps our laughter cannot ignore this either and it becomes (almost) all too easy to empathize with the politically cynical.

Although cynicism can be deactivating—or, maybe more accurately, an addicting depressant—it does almost always leave us with an open invitation to (re)imagine what can, needs, to be done: How do we disturb people who already “know” everything, people who already witness the horrors of social indifference, state-sanctioned violence, unchangeable systems of power, etc.? Does art do it anymore? Can comedy still agitate?

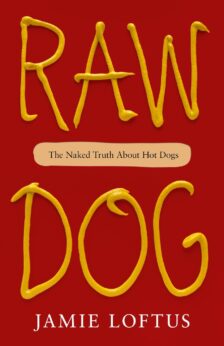

Nearly a year after the global wave of protests and solidarity in the name of George Floyd, comedian and self-proclaimed “hot dog historian” Jamie Loftus set off on a road trip to eat hot dogs across the nation. Raw Dog: The Naked Truth About Hot Dogs explores the regional differences in hot dog preparation, the mythological and real histories of hot dogs, and the mostly destructive role this supposedly American food has played economically and politically.

Nearly a year after the global wave of protests and solidarity in the name of George Floyd, comedian and self-proclaimed “hot dog historian” Jamie Loftus set off on a road trip to eat hot dogs across the nation. Raw Dog: The Naked Truth About Hot Dogs explores the regional differences in hot dog preparation, the mythological and real histories of hot dogs, and the mostly destructive role this supposedly American food has played economically and politically.

Thanks to colonization, German street vendors, and Yale “shitbird frat boys” of yesteryear, alongside the perpetuation of American exceptionalism, hot dogs are unquestionably lodged in the arteries of Americana. It is against this background that Loftus’s Hot Dog Summer commences, giving us a glimpse into their appeal and how Loftus herself tempts the fate of having multiple-dog days throughout her trip.

Raw Dog begins its travelogue in the Southwest, but not before a content warning, an introduction to her hot dog snobbery (which is suffused with ambivalence toward the food itself), and a brief history of how these meat tubes got such a chokehold over the U.S. The latter gives us insight into how Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and the porous laws—the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act—laid a foundation for hot dogs to become staples during the Great Depression.

Along the way, Loftus dives head first into which traditional hot dogs (from Depot to Dodger Dogs) are worth one’s time and which are bloated myths, and why (Hint: it’s almost always economical). Against all odds, Loftus ends up falling in love with American icon Joey Chestnut.

Although she anticipates the backlash for some of her positions by addressing them throughout the regional differences in hot dog preparation—e.g., being both pro-ketchup and anti-anti-ketchup—others are absolutely undeniable and stated as such: “Coney Islands are actually best eaten in Detroit.” But Raw Dog is not a movable feast with history peppered in. This is just the context of a work that has far reaching tentacles.

Loftus set out in the summer of 2021, a time when history was impossible to ignore and police violence was given new life. It was also at this time when many executives and managers thought they were saying something new when the disaffected didn’t immediately return to work. On her journey, she encounters sign after sign “apologizing” for longer wait times due to the fact that “no one wants to work anymore.”

Perhaps the true brilliance of Raw Dog resides in its totalizing blend of critique and comedy, which is not to say that Loftus repeats a stand-up routine stylization while recounting the history of processed foods in lower income neighborhoods. Rather, Raw Dog not only has the desired (and unexpected) moments of laughing out loud that can be difficult to get from reading but it will—and please excuse coupling the book’s title with this—make you feel something as well.

For example, as Loftus attempts to answer the age-old question “Who is fucking on the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile?” she meets Lauren, one of 12 college students recruited for a yearlong residency as Wienermobile driver. After wading through the romance-less story of Lauren and her co-driver Nick, Lauren confides about the dangers of the job, which the actual driving or long days do not seem to come close to registering. From creepy older men who unabashedly flirt with Lauren to stalkers who attempt to break down the Wienermobile’s doors to get at her inside, the threat of sexual violence is a danger that not even the innocence of Oscar Mayer branding can dilute. Lauren laments that she wishes she didn’t need to have bear spray in her pocket. Loftus understands this all too well as she walks to the train later with her keys between her fingers.

Raw Dog does not simply critique class antagonisms, power dynamics, and the rightist ideologies that allow for the state’s love of indifference. It also tells the story of how capitalism is killing Jamie, how the logic permeated a pandemic that ended up taking so many from us, and how both the difficulty of coping and reconciliation have played out since. Perhaps this is clearest in how nostalgia has all but completely replaced history. As Loftus points out, the “financially predatory late-capitalist illness called nostalgia” cannot be explained in reasonable terms and clearly feeds off its inherent romance more than anything else. For example, the superstition that “no one wants to work anymore” bears witness to how intoxicating nostalgia is: Not only are these bosses missing—envious for a time that may never have existed, but even the reader is now transported back to a time between mass layoffs when things were only a different type of horrible yet feels laughably safe now.

When a comedian puts out a book, the expectation is to unexpectedly laugh out loud in moments of silence, and this work meets that expectation. However, Loftus gives us something that feels new with Raw Dog, something that feels like comedy can still be subversive. During a time when both political correctness and those lamenting PC culture demand that comedy be “pure,” Loftus’s work (from Raw Dog to her podcasts on spiritualism, Mensa, to her insightful articles) appears to put the contemporary argument “you can’t joke about anything anymore” under the microscope: When one’s comedy is about political economy, power dynamics, sexual violence, and ideology, one is no longer simply writing punchlines but laughing at comedy itself. This is where Loftus is at her best: Poking fun at the histories, lies, and violence that have all been accepted as normal and necessary, or, worse, integral to a “good joke.”

If Raw Dog points to anything, it’s that the form of comedy today speaks to dated cynicism which can no longer appear as innocent or useful. A new form of comedy is needed. Or, as Loftus succinctly puts it, “Hot dog summer giveth and it taketh away.”

Jamie Loftus

Raw Dog: The Naked Truth About Hot Dogs

Tor Publishing Group, 2023, 320 pp.

ISBN-13: 9781250847744

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!