Jesús Colón (1901-1974) was born in Cayey, Puerto Rico, after the Spanish-American War, when the American Tobacco Company gained control of most of the tobacco-producing land in Puerto Rico. His father was a baker and his family owned the “Colón Hotel.”

His home was behind the town’s cigar factory, which hired “readers” to read stories and current events to the employees while they worked. As a child, Colón visited the factory to listen to these stories. There, he was exposed to the writings of Karl Marx and Émile Zola. From these ideas he formed a personal socialist ideology and also an interest in both the spoken and written word. The family moved to San Juan where he continued his education at the Jose Julian Acosta School.

In 1917, when he was 16, he boarded the S.S. Carolina as an employee and landed in Brooklyn, N.Y. There he went to live with his older brother, Joaquin Colón. He worked in various unskilled jobs and was able to observe the deplorable conditions of the working class of the time.

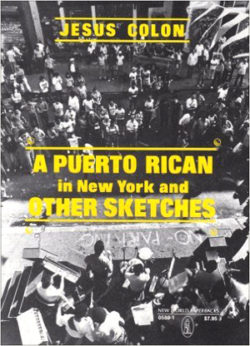

Colón was black, and was discriminated against because of the color of his skin and because of his difficulty speaking the English language. He wrote about his experiences as well as those of other immigrants. He was the first Puerto Rican to do so in English. His best-known work, “A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches,” inspired other writers.

Colón began a Spanish-language newspaper and in 1955 he wrote a regular column for the Daily Worker, predecessor of today’s People’s World. Colón was also the president of “Hispanic Publications” which published history books, political pamphlets and literature in Spanish.

During the McCarthy era of political repression in the 1950s, Colón was called to testify in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in Washington. He outraged the committee when he stated, “I will not cooperate with this committee in its aim to destroy the Bill of Rights and other constitutional rights of the people.”

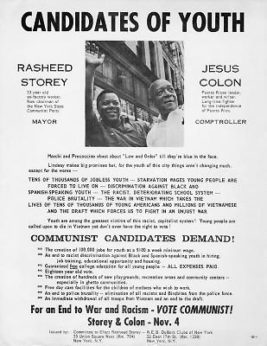

In 1969, Colón sought the office of comptroller of the city of New York, running with Rasheed Storey, candidate for mayor, on the Communist Party ticket. Among their demands were the creation of jobs for youth at minimum weekly salaries, free day care for children of working mothers, an end to police brutality through the elimination of prejudiced offers from the police force, and an end to the draft and the Vietnam War.

Colon was married twice: once to his wife Concha, and after her death in 1958 to Clara Colon, a feminist and social activist. He survived both of them.

Colón died in New York City in 1974. In accordance with his wishes, his body was cremated, returned to Puerto Rico and scattered over River La Plata in Cayey, where the river goes to the north of Puerto Rico and into the Atlantic Ocean.

The collection of Jesús Colón Papers is held at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY) in their Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora. The collection was a gift of the CPUSA and Benigno Giboyeaux.

Colón’s writings are included in many anthologies, compilations and booklets. International Publishers President Betty Smith [now retired] told the World that her company has had “a great many requests to reprint one or more sketches from Colón’s book, A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches,” published by International Publishers.

Smith said, “The New York State Department of Education selected several to reprint in a multicultural reader for New York schools. Cultural centers have also requested permission to use material from the book in their works. The book was first printed in 1962 and reprinted in 1982, 1991 and 2002. Since 1982, the covers have photographs by Tony Velez of New York Puerto Rican street festivals, and drawings by Ernesto Ramos Nieves, with a foreword by Juan Flores. Two of the sketches and other facts of Colón’s life were dramatized this past year in the play ‘The Red Rose,’ produced by Pregones Theater in the Bronx, N.Y.”

The biography includes Wikipedia and other sources. Barbara Russum contributed to this article.

The following are two excerpts from A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches.

A hero in the junk truck

By Jesús Colón

How many times have we read boastful statements from high educational leaders in our big newspapers that while other countries ignore the history and culture of the United States, our educational system does instruct our children in the history and traditions of other countries?

As far as instruction in the most elementary knowledge of Latin America is concerned, we are forced to state that what our children receive is a hodgepodge of romantic generalities and chauvinistic declarations spread further and wider by Hollywood movies.

We do not have to emphasize that the people are not to blame.

Blame rests on those persons and reactionary forces that represent and defend the interests of finance capital in education.

Last summer my wife and I had an experience that could be presented as proof of our assertion.

We were passing by, on bus No. 37, my wife and I.

“Look, Jesus, look!” said my wife pointing excitedly to a junk truck in front of the building that was being torn down. A truck full of the accumulated debris of many years was parked with its rear to the sidewalk, littered with pieces of brick and powdered cement

Atop the driver’s cabin of the truck and protruding like a spangled banner, was a huge framed picture of a standing figure. Upon his breast was a double line of medals and decorations.

“Did you notice who the man was in that framed picture?” my wife asked insistently as the bus turned the comer of Adams and Fulton Street.

“Who,” I answered absent-mindedly.

“Bolivar,” my wife shouted.

“Who did you say he was?” I inquired as if unduly awakened from a daze.

“Bolivar, Bolivar,” my wife repeated excitedly and then she added, “and to think that he is being thrown out into a junk truck,” she stammered in a breaking voice.

We got out of the bus in a hurry. Walked to where the truck was about to depart with the dead waste of fragments of a thousand tilings. The driver caught us staring at the picture.

“What do you want?” he shouted to us in a shrill voice above the noise of the acetylene torch and the electric hammers.

“You know who he is,” I cried back pointing at the picture tied atop the cabin of the driver’s truck like Joan of Arc tied to the flaming stake.

“I don’t know and I don’t care,” the driver counter-blasted in a still higher pitch of voice. But I noticed that there was no enmity in the tone of his voice, though loud and eardrum-breaking.

“He is like George Washington to a score of Latin American countries. He is . . .”

“You want it?” he interrupted in a more softened voice.

“Of course!” my wife answered for both of us, just about jumping with glee.

As the man was un-roping Bolivar from atop the truck cabin, the usual group of passersby started clustering around and encircling us — the truck driver, my wife, myself and Bolivar’s painting standing erect and magnificent in the middle of us all.

“Who is he, who is he?” came the question of the inquiring voices from everywhere. The crowd was huddled on top of us, as football players ring themselves together bending from their trunks down when they are making a decision before the next play. “Who is he, I mean, the man in the picture?” they continued to ask.

Nobody knew. Nobody seemed to care really. The question was asked more out of curiosity than real interest. The ones over on the third line of the circle of people craned their necks over the ones on the second and first lines upping themselves on their tip toes in order to be able to take a passing glance at the picture. “He is not an American, is he?” someone inquired from the crowd.

My wife finally answered them with a tinge of pride in her voice. “He is Simon Bolivar, the liberator of Latin America.”

Curiosity fulfilled, everybody was on his way again. Only my wife, myself and Bolivar remained.

Well, what to do next. It was obvious that the bus driver would not allow us in the bus with such a large framed painting going back home. Fortunately we have a very good American friend living in the Borough Hall neighborhood.

“Let us take him to John’s place until we find a person with a car to take Bolivar to our home,” I said. My wife agreed.

We opened the door of John’s apartment.

“I see that you are coming with very distinguished company today — Bolivar,” he said, simply and casually as if he had known it all his life.

John took some cleaning fluid and a soft rag and went over the whole frame in a loving and very tender manner.

We heard a knock at the door. In came a tall and very distinguished looking man dressed in black, a blend of Lincoln and Emerson in his personality. “He is a real representative of progressive America,” John whispered to us. The reverend spoke quietly and serenely. Looking at the picture he said just one word:

“Bolivar!”

And we all felt very happy.

Excerpted from A Puerto Rican in New York

The story of Ana Roque

By Jesús Colón

Her full name was Ana Roque de Duprey. She was born in the city of Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, in 1853. Ana Roque de Duprey was one of the most remarkable women ever born in Puerto Rico.

Ana Roque was able to read, write and solve elementary problems of arithmetic at the age of 3. At the age of 9 she had mastered all there was to learn in the schools of those days.

At the ripe old age of 11, Ana Roque de Duprey was a supplementary teacher in one of the few schools that we had in Puerto Rico at that time.

When Ana was informed there was no textbook to teach geography, she went to work and wrote a book on universal geography. She also wrote a book on “The Botany of the Antilles” and many other books, pamphlets and papers, including 32 novels.

Ana was perhaps the only woman in all San Juan who had a telescope on the roof of her house. Her researches in astronomy were recognized by the Astronomical Society of France, which made her an honorary member.

When feminism started to spread over England and the United States, Ana Roque was instrumental in bringing to Puerto Rico the first currents of the women’s rights movements as understood in those early days. Ana Roque was the founder of the first Puerto Rican feminist society. In 1917 she founded “La Mujer del Siglo XX” (Twentieth Century Woman), the first magazine to deal with women’s problems in Puerto Rico.

Thus, Ana Roque had a number of “firsts” in Puerto Rican history. She was our first astronomer, the first newspaperwoman. She was the first woman to be made doctor honoris causa by a Puerto Rican university. Ana Roque was also made honorary president of the Puerto Rican Association of Women Voters of which she was one of the founders.

This aspect of women’s rights — a woman’s right to vote — was one to which Ana Roque dedicated many years of her life to make a reality.

In 1929 the Puerto Rican legislature passed a law giving Puerto Rican women the right to vote. Since then many women have been elected.

Most of these achievements were the result of women’s rights movements started around the second decade of the present century, inspired and directed by women like Ana Roque de Duprey.

In 1929, Ana Roque, then in her late 70s, made herself ready to go out and vote. She always had said one of the greatest thrills in her life, one of her most precious fulfillments would be the day when she could go out and exercise her civic right to vote as men had been doing for many years. As she was now very old and not so strong and healthy as she was in her younger years, she was brought out into the streets in a wheelchair, lovingly pushed by a dozen friendly hands to the voting place. Newspapermen and a great number of people were present. They wanted to tell the Puerto Rican world that they were present when Ana Roque de Duprey — the woman who had contributed so much to make women’s right to vote come true — was herself exercising this right, one of the most important citizens’ rights.

For many days and nights throughout many years, one of the most outstanding women in Puerto Rico’s history, Ana Roque de Duprey — mathematician, astronomer, writer and fighter for women’s rights — had thought about this moment in which she, herself, would be voting like any other citizen.

The cameramen with their cameras ready and the newspapermen, pencil and paper pad in hand, were alert to preserve for posterity this moment in the life of a woman who had done so much for Puerto Rican women.

People from all walks of life invaded the polling place to see Ana Roque in the act of performing one of the greatest ambitions of her life: to vote, just like a man.

But Ana Roque was never able to realize her great ambition. For she had forgotten to register. In those early years of the 1930s, as now, you could not vote if you did not register. You must register in order to vote.

Ana Roque, in her immaculate black dress and her white pique collar, that she liked to wear so much, was taken in her wheelchair from polling place to polling place in the fruitless hope of finding out if her name was perhaps registered in some other place than the one in which she was supposed to vote.

It was all in vain. This woman, who had done so much to win the right to vote for Puerto Rican women, died soon after in 1933, at the age of 80, without ever being able to vote in her whole life. She had forgotten to register.

Excerpted from A Puerto Rican in New York

A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches, by Jesús Colón

A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches, by Jesús Colón

International Publishers New York

204 pages. Paperback, $7.95, ISBN: 978-0-7178-0589-1.