LOS ANGELES — The litany of names never ends. It didn’t begin with George Floyd, and it didn’t end with him. Black people are being slaughtered and nothing is done to contain the epidemic. Mostly it comes from the police, from neighbors, or self-appointed vigilantes. It’s a rare victory for justice when one of the killers is convicted. Police departments have to be subject to civilian review and reform, and the U.S. simply must confront its criminal laissez-faire addiction to guns. The leading cause of death among children in America is gunshot. How sick is that? Gun control advocates are hoping the November elections, all up and down the ballot, will open up space for change.

There’s a certain age—as Jonathan Lethem observes in The Fortress of Solitude—when a Black boy learns he’s scary. His very existence, his presence on the street or in the schoolyard. Scary. And not just in the Deep South. Everywhere in America.

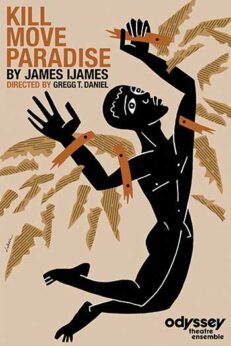

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright James Ijames (for Fat Ham) tackles this issue in a 2017 play now receiving its Southern California premiere. Odyssey Theatre Ensemble presents his Kill Move Paradise, sometimes humorous and uplifting, but ultimately packing a powerful punch, directed by Gregg T. Daniel in an eight-week run through Nov. 3.

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright James Ijames (for Fat Ham) tackles this issue in a 2017 play now receiving its Southern California premiere. Odyssey Theatre Ensemble presents his Kill Move Paradise, sometimes humorous and uplifting, but ultimately packing a powerful punch, directed by Gregg T. Daniel in an eight-week run through Nov. 3.

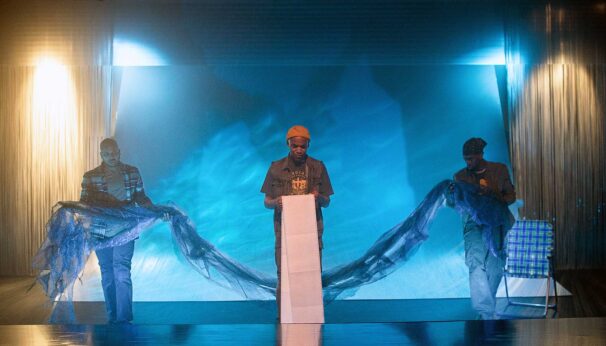

For a tense, energetic 80 minutes without intermission, we find ourselves in “a Space of transition between life and the afterlife, reminiscent of Elysium.” Four Black men have been murdered, torn from the world without warning—a traffic stop gone wrong, a playground.

Each attempts to escape back into the only reality they have known—life on Earth—but are thwarted by high walls and electric shocks on all sides, even on the “fourth wall” separating them from the public, whom they can see, much like the recently passed residents of Grover’s Corner, N.H., in Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town, who gaze down on their neighbors and family and must accept their powerlessness to affect life on Earth. We in the audience are constantly reminded that this “fourth wall” does not exist—except electronically: They are watching us, a “representative slice” of the American public, as much as we are watching them. More than that, the first man, Isa, says: “They like to watch.”

They are stuck in this obligatory waiting room, at least for long enough that they accept their fate in—well, the author says it in the title—paradise, which is somewhat reassuring, for what it’s worth. We meet them one by one as they arrive—Isa (Ulato Sam), Daz (Ahkei Togun), Grif (Jonathan P. Sims), and Tiny (Cedric Joe)—and try to figure out how they arrived in this unearthly place. Their adaptation depends, in part, on how well they treat the newcomers on this never-expected journey. The last to show up is a young teenager fascinated by alien, outer space dramas who is still holding his bright blue plastic toy zap gun in hand. It doesn’t take much imagination to figure out how his life was taken from him.

As they enter the stage, they report items they have seen in an anteroom—everyday articles of furniture and clothing that had to be left behind before entering this next waystation. As young men will, they tease and taunt one another, play games, sing corner doo-wop, dance, and uplift one another from despair as they realize they’re never going back to the life they knew. These guys are real athletes on stage: It’s a highly physical show. At the same time, Ijames is a real poet: Each character has his own rhythm, speech patterns, and manner of metaphorizing the world.

On stage is only one prop: an old-fashioned teletype machine spitting out a continuous ticker tape of names. Names of Black men, women, and children assassinated by gun-toting Americans for their race. The recitation of these names occupies several minutes’ worth of stage time. We cannot turn away, we cannot unhear them. This phase of their existence is represented by the central word of the play’s title: Move. Even death is not static, not the end. The veterans have the responsibility of bringing peace and comfort to those who come later, to create a brotherhood, to make this house a home. This form of grace is the necessary link between Kill and Paradise.

Isa claims, “We are the martyrs. We sacrificed for others to live,” reflecting a solacing religious belief. But the worldly-wise Daz hears it and explodes, bashing that “fucked-up salvation cosmology.” He will have none of it: He’d just been selling CDs and DVDs on the street.

“I wanted to create a space in which the humanity of the people on stage is undeniable,” Ijames said in an interview. “These characters embody all the ways in which we try to be human. They are jealous, they are kind, they are maternal and paternal, and they are pushed physically to the edge of something and then fall. I always say that I hope this play becomes obsolete one day. That’s like a crazy thing for a playwright to say. But I hope one day that people will say we don’t need to do this play anymore because we are different. We are better.”

“Kill Move Paradise deals with ongoing violence against Black and Brown people in a highly original and unique way,” says director Daniel. “The audience will laugh…while also feeling invested in the pain our heroes are feeling. We relate to these four young men as they find the humor in their situation, celebrate their culture, and revel in one another. It’s hard to hate someone when you get to know them. This is a kind of politically motivated theater I haven’t seen in some time.”

“Kill Move Paradise deals with ongoing violence against Black and Brown people in a highly original and unique way,” says director Daniel. “The audience will laugh…while also feeling invested in the pain our heroes are feeling. We relate to these four young men as they find the humor in their situation, celebrate their culture, and revel in one another. It’s hard to hate someone when you get to know them. This is a kind of politically motivated theater I haven’t seen in some time.”

The Odyssey’s creative team includes scenic designer Stephanie Kerley Schwartz; associate scenic designer Mark Mendelson; lighting designer Donny Jackson; composer and sound designer David Gonzalez; costume designer Wendell C. Carmichael; choreographer Toran X. Moore; and graphic artist Luba Lukova. The stage manager is Jenny Nwene. Sally Essex Lopresti produces for Odyssey Theatre Ensemble.

When the play ended, I wondered if acceptance of their suddenly acquired eternity was a fair deal for these murdered men. Where is the justice? I practically howled. And then the author’s point became clear. The justice must come not from the characters on stage but from the people in the audience, who know and remember all the names. From us who are still here on Earth and capable of making change. Yes, we “like to watch.” No one experiencing the play will go away unmoved. But moved to act?

Performances of Kill Move Paradise take place on Fri. and Sat. at 8 p.m. and Sun. at 2 p.m. through Nov. 3. There will be two additional weeknight performances, on Weds., Sept. 25, and Weds., Oct. 16, each at 8 p.m., each of which will be followed by a post-show discussion. The third Fri. of Oct. (the 18th) is “Wine Night”: enjoy complimentary wine and snacks and mingle with the cast after the show. The Odyssey Theatre is located at 2055 S. Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles 90025. “College Nights” on Fri., Sept. 27, and Fri., Oct. 18 are Pay-What-You-Can (reservations open online and at the door starting at 5:30 p.m.).

For more information and to purchase tickets, call (310) 477-2055 or go to OdysseyTheatre.com.