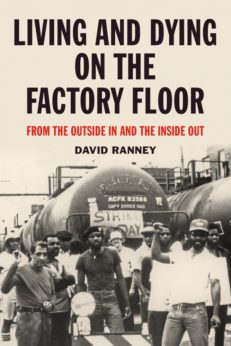

WASHINGTON—There can be a big gap between the halls of academia—and scholars’ studies about jobs—and the real life of work, including bosses’ treatment of workers. And David Ranney’s Living and Dying on the Factory Floor illuminates it.

Ranney, a retired University of Illinois at Chicago professor, talks about his work for seven years in union and non-union shops on Chicago’s far Southeast Side and nearby Northwest Indiana. He toiled at those jobs between teaching stints.

Ranney, a retired University of Illinois at Chicago professor, talks about his work for seven years in union and non-union shops on Chicago’s far Southeast Side and nearby Northwest Indiana. He toiled at those jobs between teaching stints.

Forty years later, he went back to talk with people and see what his old industrial area is like today. It’s not pretty.

Many of the problems Ranney encountered on shop floors and in the surrounding community—a neighborhood now bereft of the heavy and light industry that kept it going for decades—still remain, he said at a recent book talk at the Institute for Policy Studies.

And not just in the Chicago area, but nationwide, he explained. They include tensions over class and race and that wide gap between academic studies and the factory floor.

There were well-paying jobs at those plants Ranney worked in from 1976-82. The workers may not have enjoyed them, in lousy working conditions with bosses exploiting them, but pay was a route into the middle-class. At one plant, the starting wage was equivalent to $24 an hour today.

“The whole issues of race and class are still with us” on factory floors, Ranney said at the September book talk. “And what the heck is a middle-class job?”

Those jobs are gone, and NAFTA, Ranney says, is a big reason. The Southeast Chicago-Northwestern Indiana industrial belt, at its height, “had hundreds of factories and 1.5 million workers. It was the largest factory area in the world.” U.S. Steel’s South Works “alone had 20,000 workers. Now it’s a 600-acre polluted vacant lot.

“And there was environmental pollution. What the companies were doing” to the surrounding land on the South Side and to nearby Lake Michigan, Ranney said, was criminal. It also affected the workers, who lived close to the plants and the slag heaps, surface oils, and pollution the firms dumped. “We don’t want to bring that back again,” Ranney commented.

Immigration problems, too, are almost identical, Ranney said. Even 40 years ago, “our plants were getting raided by the migra,” the Hispanic nickname for what is now the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

In that case, though, the workers overcame racial divides. When INS descended on the plant he features in the book, Chicago Shortening, where workers manufactured industrial cooking oils, everyone banded together “to spirit the Mexican workers away.”

And it is Chicago Shortening and events there, from a wildcat strike to the murder of a strike leader and more, that forms the center of the book.

A local of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butchers’ Workmen then represented the workers. The local, however, was under control of the plant bosses—a company VP was also the union business agent—and the Mob. There were racial tensions, which the bosses exploited, Ranney said. Most of the workers were people of color and “one of the few white workers was identified later as a Nazi,” he noted. The bosses even co-opted the local’s lawyer.

Eventually, exploitation at Chicago Shortening grew so bad the workers had to engage in a wildcat strike. It lasted ten weeks, and workers gained some wins and some hard-won knowledge. “When we asked for binding arbitration” of grievances “and they (bosses) quickly agreed, we should have smelled a rat,” said Ranney, an outspoken strike supporter.

“It was a trauma,” Ranney told the IPS group. The strike leaders were illegally fired, and the National Labor Relations Board and a federal judge eventually ruled the firm had to take them back, with back pay “and without the scabs” Chicago Shortening had brought in.

That didn’t stop the tension. The leader of the strikers, Charles Taylor, a charismatic young African American, “was stabbed to death” in the plant after the strike ended.

His funeral, at least, produced another instance of unity: When a white-owned funeral home refused to conduct the services, even though they had been paid for, an African-American-owned funeral home did. And a racially mixed crowd attended.

All this affected Ranney’s teaching, when he returned to academia, at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He brought real-world knowledge equaled by few, if any, of his colleagues—or by the white-collar-centered greater society that has arisen in the 40 years since.

“I had been teaching microeconomics,” he explained. “Now, I knew about the silly abstractions” professors cite “and I also know how it (microeconomics) affected real people. Rather than rant at people about class and race, we should realize that when class” comes to the fore, and workers unite as a class against bosses, “racism can go away.”

Ranney sees some hope now: The remaining workers and community allies on the far South Side, he says, are organizing across racial lines against area environmental destruction that the 1% inflicted. “Class dynamism comes out in the course of a real struggle,” he concludes.

Living and Dying on the Factory Floor is available from PM Press.