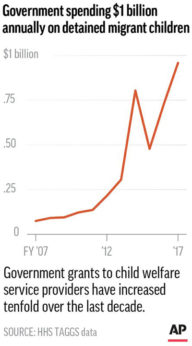

SAN ANTONIO (AP)—Detaining immigrant children has morphed into a surging industry in the U.S. that now reaps $1 billion annually—a tenfold increase over the past decade, an Associated Press analysis finds.

Health and Human Services grants for shelters, foster care, and other child welfare services for detained, unaccompanied, and separated children soared from $74.5 million in 2007 to $958 million in 2017. The agency is also reviewing a new round of proposals amid a growing effort by the White House to keep immigrant children in government custody.

Health and Human Services grants for shelters, foster care, and other child welfare services for detained, unaccompanied, and separated children soared from $74.5 million in 2007 to $958 million in 2017. The agency is also reviewing a new round of proposals amid a growing effort by the White House to keep immigrant children in government custody.

Currently, more than 11,800 children, from a few months old to 17, are housed in nearly 90 facilities in 15 states—Arizona, California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and Washington.

They are being held while their parents await immigration proceedings or, if the children arrived unaccompanied, are reviewed for possible asylum themselves.

In May, the agency issued requests for bids for five projects that could total more than $500 million for beds, foster and therapeutic care, and “secure care,” which means employing guards. More contracts are expected to come up for bids in October.

The agency’s current facilities include locations for what the Trump administration calls “tender age” children, typically under 5. Three shelters in Texas have been designated for toddlers and infants. Others—including in tents in Tornillo, Texas, and a tent-and-building temporary shelter in Homestead, Florida—are housing older teens.

Over the past decade, by far the largest recipients of taxpayer money have been Southwest Key and Baptist Child & Family Services, AP’s analysis shows. From 2008 to date, Southwest Key has received $1.39 billion in grant funding to operate shelters; Baptist Child & Family Services has received $942 million.

A Texas-based organization called International Educational Services also was a big recipient, landing more than $72 million in the last fiscal year before folding amid a series of complaints about the conditions in its shelters.

The recipients of the money run the gamut, including nonprofits, religious organizations, and for-profit entities. The organizations originally concentrated on housing and detaining at-risk youth, but shifted their focus to immigrants when tens of thousands of Central American children started arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border in recent years.

They are essentially government contractors for the Health and Human Services Department—the federal agency that administers the program keeping immigrant children in custody. Organizations like Southwest Key insist that the children are well cared for and that the vast sums of money they receive are necessary to house, transport, educate, and provide medical care for thousands of children while complying with government regulations and court orders.

The recent uproar surrounding separated families at the border has placed the locations at the center of the controversy. A former Walmart store in Texas is now a Southwest Key facility that’s believed to be the biggest child immigrant facility in the country, and First Lady Melania Trump visited another Southwest Key location in Phoenix.

“You can’t put a child in a prison. You cannot. It’s immoral,” said Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, a New York Democrat who has been visiting shelters.

Gillibrand said the shelters will continue to expand because no system is in place to reunite families separated at the border. “These are real concerns that the administration has not thought through at all,” she said.

In April, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a “zero tolerance policy” directing authorities to arrest, jail, and prosecute anyone illegally crossing the border, including people seeking asylum and without previous offenses. As a result, more than 2,300 children were turned over to HHS.

In a recently released report, the State Department decried the general principle of holding children in shelters, saying it makes them inherently vulnerable.

“Removal of a child from the family should only be considered as a temporary, last resort,” the report said. “Studies have found that both private and government-run residential institutions for children, or places such as orphanages and psychiatric wards that do not offer a family-based setting, cannot replicate the emotional companionship and attention found in family environments that are prerequisites to healthy cognitive development.”

Some in the Trump administration describe the new policy as a “deterrent” to future would-be immigrants and asylum-seekers fleeing violence and abject poverty in Central America, Mexico, and beyond.

But Steven Wagner, acting assistant secretary for the Administration for Children and Families—an HHS division—said the policy has exposed broader issues over how the government can manage such a vast system.

“It was never intended to be a foster care system with more than 10,000 children in custody at an immediate cost to the federal taxpayer of over $1 billion dollars per year,” Wagner said in a statement.

The longer a child is in government custody, the potential for emotional and physical damage grows, said Dr. Colleen Kraft, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The foundational relationship between a parent and child is what sets the stage for that child’s brain development, for their learning, for their child health, for their adult health,” Kraft said.

“And you could have the nicest facility with the nicest equipment and toys and games, but if you don’t have that parent, if you don’t have that caring adult that can buffer the stress that these kids feel, then you’re taking away the basic science of what we know helps pediatrics.”

A judge in California has ordered authorities to reunite separated families within 30 days—and the government has completed more than 50 of the reunions of children under 5 by Thursday.