CHARLESTON, S.C. (AP)—Housing Secretary Ben Carson says his latest proposal to raise rents would mean a path toward self-sufficiency for millions of low-income households across the United States by pushing more people to find work. For Ebony Morris and her four small children, it could mean homelessness.

Morris lives in Charleston, South Carolina, where most households receiving federal housing assistance would see their rent go up an average 26 percent, according to an analysis done by Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and provided exclusively to The Associated Press. But her increase would be nearly double that.

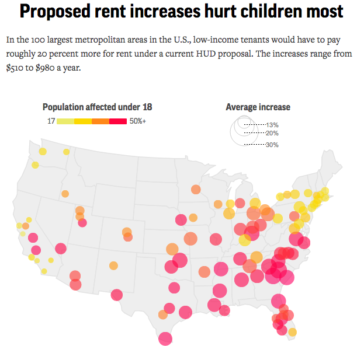

Overall, the analysis shows that in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas, low-income tenants—many of whom have jobs—would have to pay roughly 20 percent more each year for rent under the plan. That rent increase is about six times greater than the growth in average hourly earnings, putting the poorest workers at an increased risk of homelessness because wages simply haven’t kept pace with housing expenses.

“I saw public housing as an option to get on my feet, to pay 30 percent of my income and get myself out of debt and eventually become a homeowner,” said Morris, whose monthly rent would jump from $403 to $600. “But this would put us in a homeless state.”

Roughly 4 million low-income households receiving HUD assistance would be affected by the proposal. HUD estimates that about 2 million would be affected immediately, while the other 2 million would see rent increases phased in after six years.

The proposal, which needs congressional approval, is the latest attempt by the Trump administration to scale back the social safety net, under the belief that charging more for rent will prompt those receiving federal assistance to enter the workforce and earn more income. “It’s our attempt to give poor people a way out of poverty,” Carson said in a recent interview with Fox News.

The analysis shows that families would be disproportionately impacted. Of the 8.3 million people affected by the proposal, more than 3 million are children.

That stands in stark contrast to Carson’s focus on children and education, which is woven into his memoirs and embedded in the very foundation of his namesake reading rooms tucked into elementary schools across the country. It also runs contrary to research, housing experts say.

“There’s no evidence that raising rents causes people to work more,” said Will Fischer, a senior policy analyst at the policy center, which advocates for the poor. “For most of these rent increases, I don’t think there’s even a plausible theory for why they would encourage work.”

One rainy spring morning Morris tried to wrangle her rowdy children into a minivan as they chased each other in a circle in the yard, a small patch of grass in front of the low-slung red brick house she rents in a housing complex. She’d taken a rare day off work so she could attend a school orientation.

Morris moved to Charleston three years ago from Summerville, South Carolina, to go to school. She’s since earned her associate’s degree in health science. She’s a full-time pediatric assistant, sometimes working 50 hours a week just to get by. Her children, ages 3, 4, 7 and 10, would be hit hardest by the rent increase, she said.

“Food, electricity bills, school uniforms,” she said. “Internet for homework assignments and report cards. All of their reading modules at school require the internet, without it they’ll be behind their classmates. The kids are in extracurriculars, those would be scrapped. I would struggle just to pay my bills. It would be very, very, very hard.”

The impact of the rent proposal would affect low-income residents and families everywhere.

Rent for the poorest tenants in Baltimore, where Carson made history as a neurosurgeon at Johns Hopkins Hospital and where his own story of overcoming poverty inspired generations of children to dream of possibilities beyond the projects, could go up by 19 percent or $800 a year. In Detroit, where Carson’s mother, a single parent, raised him by working two jobs, low-income families could see their rents increase by $710, or 21 percent. Households in Washington, D.C., one of the richest regions in the country, would see the largest increases for its poorest residents: $980 per year on average, a 20 percent jump.

“This proposal to raise rents on low-income people doesn’t magically create well-paying jobs needed to lift people out of poverty,” said Diane Yentel, CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “Instead it just makes it harder for struggling families to get ahead by potentially cutting them off from the very stability that makes it possible for them to find and keep jobs.”

The “Make Affordable Housing Work Act,” announced on April 25, would allow housing authorities to impose work requirements, would increase the percentage of income poor tenants are required to pay from 30 percent to 35 percent, and would raise the minimum rent from $50 to $150 per month. The proposal would eliminate deductions, for medical care and child care, and for each child in a home. Currently, a household can deduct from its gross income $480 per child, significantly lowering rent for families.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development says elderly or disabled households would be exempt from the changes, but an estimated 314,000 households stand to lose their elderly or disabled status and see their rents go up, according to the outside analysis.

Donald Cameron, president and CEO of the Charleston Housing Authority, said HUD’s proposed rent increases would be “catastrophic” for the city and metropolitan area.

“We’d lose a lot of people within a very short time: the ones with the smallest pocket books, the least discretionary income,” he said. “What do they do? If you take away that safety net, they’re in free fall. Where do they go?”

Charleston, with its winding cobblestone walks, sweeping river views and live oaks draped with Spanish moss, is a case study in economic disparity. The city is booming, drawing millions of tourists each year. Boeing opened a propulsion plant in North Charleston in 2015 and Mercedes Benz a factory to build Sprinter vans, bringing with it the promise of more than 1,000 jobs.

But housing prices are going up faster than wages, creating a widespread crisis for low- and middle-income families there.

Unlike many cities, Charleston’s public housing stock was built entirely for families, which is why increases here would disproportionately affect parents and their children. Roughly 55 percent of households in the city’s public housing are headed by single mothers, according to the data.

Cameron said the affordable housing shortage is so extreme that nearly half of Charleston voucher holders are forced to find housing next door in North Charleston. But that city is facing its own housing related emergency. According to data collected by Princeton University’s Eviction Lab, North Charleston’s eviction rate ranks significantly higher than other cities the program has tracked.

The data analysis was conducted using 2016 HUD data and includes tenants living in public housing complexes and receiving vouchers to rent apartments on the private market. It excludes housing authorities participating in the Moving to Work program, which allows districts to determine their own rent policies.

Melissa Maddox Evans, general counsel for the Charleston Housing Authority, said she believes the proposal is based on a faulty premise — that most tenants in public housing don’t have jobs and that rent increases will incentivize work.

“There’s an assumption that many of the participants are not employed when they are,” said Maddox Evans. “Most tenants here work two or three jobs. When they are going out and finding work, are they going to make enough to accommodate that increase?”

In areas of concentrated poverty, low-wage jobs are often the only option, particularly for those without access to a car or public transportation.

Shannon Brown, 29, recently had to leave her full-time job providing child care in North Charleston so she could pick up her daughter from the local Head Start program each afternoon. She was earning about $450 a month and paying $157 for rent.

She’s trying to find a job closer to home, to balance work and caring for her child on her own. She stayed in a shelter before moving into public housing, and worries that a rent increase could put her back there.

“I’m trying to get out of poverty,” she said, “but it’s already hard.”

Afrika Frasier had a steady job, as a manager at a Church’s Chicken restaurant down the street from the unit she shares with her husband and four children. She was making $1,200 each month and paying $300 in rent. But a few weeks ago, her boss called to tell her not to come in, that the restaurant was closing for good.

“We’re trying to get the hell out of here, but minimum wage is a big, big problem,” Frasier said. She’s since found another job, as an assistant manager at the local Family Dollar. But she worries about the viability of her opportunities in the area, and said she’s planning to move to Georgia as soon as she can.

“You can go to school, get an education, and the job you’re going to get is still going to give you $10 an hour even though we’re the ones cleaning your dishes, cooking your food. Where are we supposed to live?”

Morris doesn’t have an answer. If she’s priced out of public housing, she doesn’t know where she’ll go or what she’ll do.

“I work every day and I’m trying my hardest,” she said. “My main focus is to make sure my children are educated and to break this cycle. But taking away resources for moms? I never thought I’d be in a situation like this.”

Fenn reported from New York.