Jackie Robinson integrated—or, to be more precise, reintegrated—major league baseball in 1947, 60 years after it became segregated. Now, more than 73 years after Robinson’s debut, MLB is integrating its record book.

On Dec. 16, the majors said they will recognize the 1920-48 records of the Negro Leagues as major league records, on a par with those of the National and American Leagues.

To take Hall-of-Famer Robinson as an example, that means his major league record of an excellent .311 batting average in 4,877 at-bats, 134 home runs, 734 runs batted in, and 197 stolen bases, plus his history-making role of breaking the color line, will be yoked in the record books to his short Negro League record for the Kansas City Monarchs.

Robinson joined that successful team late in the 1945 season after he was mustered out of the U.S. Army following the end of World War II. In only 58 at-bats, he hit a stupendous .414 with one homer, 16 RBI, and two stolen bases.

Branch Rickey, then the Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager, signed Robinson, a Black multi-sport star, for that organization. Rickey sent Robinson to the franchise’s top minor league team, in Montreal, for a year and promoted him to the white leagues in 1947, at age 28. He played for ten years.

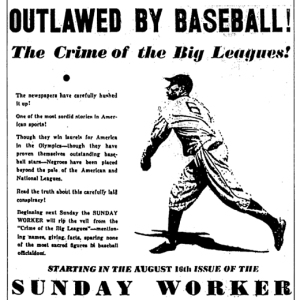

Before that breakthrough, this newspaper’s predecessor, the Daily Worker, and the Black press led the campaign for integrating white major and minor league baseball. Lester “Red” Rodney, the Worker’s sports editor from 1935-58, championed integration as a political cause.

Before that breakthrough, this newspaper’s predecessor, the Daily Worker, and the Black press led the campaign for integrating white major and minor league baseball. Lester “Red” Rodney, the Worker’s sports editor from 1935-58, championed integration as a political cause.

Rodney “launched a political sports page that was light years ahead of its time” and “vibrated with the intersection of sports and struggle,” Zirin said. He emphasized the excellence of the seven various Negro Leagues and their players in general and Robinson in particular.

Now baseball’s record book will include those Negro League numbers, even if they’re incomplete. But so are other MLB records. Batters’ strikeouts were uncounted, for example, for the first decade of the 20th century. Stolen base totals were not standardized.

The career of legendary pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige illustrates Negro League record gaps. His MLB totals, mostly as a relief pitcher, were 28 wins, 31 losses, 33 saves, and four shutouts, with a 3.29 earned run average and 288 strikeouts in 476 innings. Not exactly Hall of Fame numbers.

Of course, Satch—everybody called him by his nickname—didn’t pitch in the majors until the day he turned 42 years old. The color line had kept him out.

Before that, Satch was a dominant starting pitcher and star draw in the Negro Leagues and in barnstorming tours against white players, whom he easily outmatched. So Satch became the first Baseball Hall of Famer inducted based mostly on his Negro Leagues record, his star power, and his legendary personality, in 1971. The first Hall of Famer to push his case? Boston Red Sox great Ted Williams, a white.

But there’s even confusion about Satch’s Negro Leagues record. Baseball-reference.com gives Satch a 146-64 won-loss mark, 40 shutouts, and 1,620 strikeouts in 1,828 innings. There’s no earned-run-average number—a key statistic for pitchers—for Satch because not all of his seasons split out earned runs, which were scored without errors involved, from total runs. There are other gaps in those numbers, too.

However, a website of the pro-Negro League organization that lobbied for including Negro League stats in overall baseball records says Satch pitched 1,521 innings, had a 112-60 mark with a 2.36 ERA, and 1,469 strikeouts. Once the numbers are sorted out, Satch’s record will be in the major leagues’ books.

There are also no records for Satch in baseball-reference.com for his pitching in barnstorming games against white all-star teams, or in the Mexican League or in Latin American baseball.

For instance, the late baseball owner Bill Veeck, who signed Satch for the Cleveland Indians in 1948, said one of the greatest games he ever saw was when Satch outpitched white future Hall of Famer Dizzy Dean. Satch won 1-0 in a 16-inning complete game exhibition against white all-stars, striking out 18.

Despite the gaps, and complaints from traditionalists, MLB went ahead with its decision. “It is MLB’s view the 1969 omission of the Negro Leagues from consideration” in record books as major leagues “was clearly an error that demands today’s designation,” the majors said in their statement.

That still leaves two areas for MLB to grapple with, though: The players on the field and the executives in front offices and managerial chairs. Of the 30 current MLB teams, two have Black managers. Only 8% of players are Black, compared to the 13% Black share of the U.S. population. Front offices are also sparsely Black. The Miami Marlins just named MLB’s first female general manager, Kim Ng, an Asian-American.

Read the history of the Daily Worker’s fight to integrate baseball in PW Sportswriter Al Neal’s chapter, “First to Start the Fight: Communism, the Daily Worker, and Baseball,” in the new book FAITH IN THE MASSES, available from International Publishers.

Comments