While many readers of history undoubtedly have some familiarity with certain aspects of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), particularly the American involvement by way of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, not everyone sees the valiant fight against Generalísimo Francisco Franco’s nationalists in its greater global context.

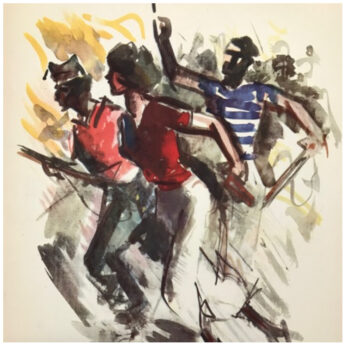

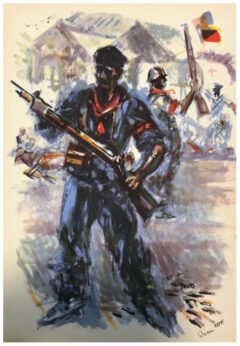

Writing as Manuel Tiago, Álvaro Cunhal, the longtime Portuguese Communist Party leader who left a legacy of “historical fiction” works behind, offers a gripping retelling of the war against fascism in Spain from the vantage point of Portuguese partisans fighting alongside the Spanish Republicans. The enemy, purposefully backed by weapons and bombing raids from already established fascist countries such as Germany and Italy, reveals in its characterization here only its angry face of inhuman terror—except that it was human beings, young men under military orders, who must be held accountable. A reader would be wise not to overlook an account like this, especially given the resurgence of fascism (often more politely called “authoritarianism”) in our times.

It is especially salient that so many people today appear to have forgotten both the murderousness of fascism and the lofty ideals that have historically stood against it—justice, democracy, and the cause of humanity embodied in those who laid down their lives in the struggle. In the case of Cunhal’s novel, a socialist vision of the future formed a part of that cause.

Eric A. Gordon’s translation of A Casa de Eulália as Eulalia’s House brings readers to a true place of interpretation of both the experience and the language of the author, as well as those of the Portuguese cadres’ Spanish camaradas. The reader enters the story from the onset with a warm sense of the author’s intent as the protagonists of the story are immediately humanized in commonly relatable ways. But as the fascist menace grows over that fateful summer of 1936, the story arc quickly transcends the commonplace and allows an intimate view of the noble cause for which the guerrillas—who had simply been friends meeting over beers and talk not unfamiliar on patios of bars in the summers of any times—were suddenly compelled to fight and to die.

The scenario that unfolds is one that was all too familiar in the 20th century, and which has repeated itself in the 21st, at least in one attempt that came dangerously close in recent history: A progressive majority wins elections, and quickly reactionaries refuse to accept the democratically decided will of the people. They retake power through violent means, which indiscriminately aims to eliminate anyone who dares to stand in their path.

The struggle against fascist brutality is exemplified in Cunhal’s use of womanhood as a symbol of the people stepping from their established roles in life and being transformed into something they essentially were not at the onset. They have become the struggle itself. They have given themselves over to that which they were not initially: The women they are now, fighters, nurses in field hospitals, battlefield medics, immerse themselves to such an extent that their previous identities are lost. The central character of Eulalia represents the people almost in a religious sense baptized by the violence that forces outside themselves foisted upon them. Eulalia is, as Tiago describes her, “A hundred percent Communist, a hundred percent Spanish, a hundred percent woman.”

The character of her mother, Madrecita, who appears more frequently than Eulalia, also represents an ideal type in the story. Like the other characters, she may be one of many actual people gathered from Cunhal’s memories of his own involvement in the fight. Whether she is historical or a composite is less important than the role she serves in her support of the fighters. She provides them with food, a place to rest, comfort, and above all moral support and encouragement. She is mother to them in a way that never fails to nurture those most deeply immersed in la lucha (or a luta in Cunhal’s Portuguese).

The terror inflicted upon the people of the Spanish Republic shows itself in a surreal and existential scene where the protagonist António happens upon a location where an obvious crime had been committed at the hands of the enemy. A man lay dead in the doorway, his face reduced to bloody pulp. He had died defending his home. A woman lay nearby him in her own blood, clothing torn, skirt raised, bare breasted. Not only has this particular rape and murder occurred in their own home, but it is emblematically a fascist rape of the people and of democracy itself.

In an interesting manner, amid the almost rhythmically inserted passages retelling urban battles where bystanders are shot and killed often at random, the main character, António, pauses and considers his party orders or directives. Rather than fighting on the front, where his passion, his heart, lay, he had the option of remaining in Madrid in his party task of maintaining contact with Spanish comrades and providing secure housing for Portuguese comrades who might arrive at any given moment. What is at stake, and what is deeply considered, is the question of party loyalty, and in this sense, Eulalia’s House strays somewhat from the neo-Realist, or Socialist Realist formula. Some real inner conflict is at issue.

At first, António agrees to the party’s request, yet within him there is always the call to the front. In ways that challenge conventional ideas concerning commitments, António struggles within himself and elevates his personal desires above the duty that was before him. Despite the decision that he felt compelled in the end to make for himself, António maintains and redefines the ideal and overarching purpose for which he struggled. Having witnessed the battles, having seen the horror and loss, a part of António belonged at the front in such a way that no force could hold him back. Not to engage in the struggle on the front lines meant giving up. Not acting upon his deepest longing was a self-betrayal—and ultimately unacceptable. António mused over the words of a friend on the battle lines. Not continuing in the fight meant giving up and “accepting eternal submission to exploitation, oppression, and injustice.” António’s choice was not a betrayal of party loyalty but was in a deeper sense his immersion into the sacred patria of democracy itself.

A fascinating device, and subtly deployed in the novel, is Tiago’s use of a number of subsidiary characters, some of them as committed to fighting fascism as the Communists—the anarchists, for example—but whom he portrays in revelatory profile and of whom he asks profound questions. Other such individuals are a trio of Portuguese political exiles in Madrid with whom, in theory, the Communists will one day have to form a strategic democratic alliance in order to overturn the fascist regime at home, but who are sketched here as basically bourgeois ditherers with no mass approach. There’s an ironically wise car dealer who keeps popping up in the story, a sympathetic outsider standing apart from the struggle. And there are two teenage boys who take on very distinct roles illustrating some of the values and choices confronting youth.

Cunhal’s work in writing the novel serves to remind people of every historical period that the securing of victories is always in the hands of regular people—workers and oppressed people—and that if fascism is to be destroyed in the end, it will happen because those who wish for a better world are willing to fight the good fight, whether on the front or elsewhere.

Indeed, this is a must read for our times! Eulalia’s House is a captivating retelling of events that immerses the reader into the lives and passions of partisan comrades waging an unconventional struggle against the forces of fascism. We can only be grateful that it is now, since its original publication in 1997, finally available in English.

Indeed, this is a must read for our times! Eulalia’s House is a captivating retelling of events that immerses the reader into the lives and passions of partisan comrades waging an unconventional struggle against the forces of fascism. We can only be grateful that it is now, since its original publication in 1997, finally available in English.

Eulalia’s House

Manuel Tiago (Álvaro Cunhal)

Translated by Eric A. Gordon

New York: International Publishers, 2002

152 pp., illustrated, with a Foreword, $15.99

ISBN: 9780717808786

Copies may be ordered here.