IRVINE, Calif. — I’ll get to my review of Gian Carlo Menotti’s The Medium and The Old Maid and the Thief in a few moments. First, though, I’d like to explain how this Italian-American composer helped to set the course for my whole life. Maybe some other readers my age will also recall his impact.

Xmas 1951

I go back to Christmas Eve 1951. I was about to turn seven. NBC television broadcast the premiere of Menotti’s hour-long opera Amahl and the Night Visitors and each Christmas Eve for several years NBC would repeat this broadcast, either with the original cast or an updated one. The first year our whole family gathered around to watch the broadcast, and in later years we made its ritual viewing a cherished part of the season. My dad and I had the whole piece practically memorized and between us all our lives we could summon up catchphrases of it. Every time any unique type of container appeared, one of us would break into, “This is my box. This is my box. I never travel without my box.”

Amahl is an enchanting, melodious tale, to Menotti’s own libretto, of a crippled boy and his mother who receive an unannounced visit from the Three Kings on their way to see the Christ child. Midway in the piece, tired from their journey, the travelers lay themselves down for sleep, and the mother can’t help staring at all the royal treasures sitting in her humble house. She becomes momentarily crazed and sings a soliloquy, the opera’s only true aria, “All that gold! I wonder if rich people know what to do with their gold.” What that wealth could do for her child! She is caught stealing, and in the dénouement, Amahl offers to give up his crutch to the newborn child (“Who know, he may need one, and this I made myself”). The grace of his gesture miraculously heals him of his condition and he joins the convoy.

The power of that mother’s aria has stayed with me always. I sometimes even wonder how such a class-conscious piece of music ever received repeated national broadcasts in the anti-Communist witch-hunt era. But of course, she is a thief—one driven by need, to be sure—and in the end apprehended and forgiven. More than the theme of her aria made an impression on me. As I grew older and developed a real love of operatic and other music, I also slowly became aware that social ideas are often expressed in these larger-than-life dramas. After all, does any composer or artist truly work in a vacuum totally disjointed from time and place? In a concrete way I can point back to 1951 and this popular family opera by an American composer as a source for so many of the intellectual and esthetic concerns I have wrestled with all my life as an academic researcher, biographer, critic, and of course as a member of the audience.

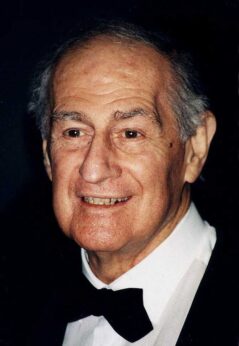

Menotti (1911-2007) was much in demand for decades, not only as a twice Pulitzer Prize recipient composer but also as the organizer of the Spoleto Festival with locales in both Italy and Charleston, S.C. Only a few of his larger works have achieved a real stake in the repertory, such as The Consul. I am especially fond of his insightful comic opera The Last Savage, which I have seen in two different productions (The Met and Santa Fe), and I deeply admire The Unicorn, the Gorgon and the Manticore, a story about conspicuous consumption set in madrigals, which I’ve never seen on stage.

Menotti wrote his own libretti, which almost always embedded some redeeming social messages. Although he lived a life of considerable privilege, as a gay man (long partnered with fellow composer Samuel Barber) and an immigrant he had a sense of empathy for the outcast and the mentally disturbed. Unfortunately, he rushed to completion many of his later works, and the results often disappointed. He slowly sank into virtual irrelevance to the evolving art, remembered almost exclusively for his work from decades before.

When I moved to New York in late 1978, I introduced myself to Adelaide Bean, cultural editor of the Daily World (a former banner of People’s World), and volunteered to do some arts reviews for the paper. It was one way of gaining entrée to opera houses and theaters. In 1979, the New York City Opera premiered Menotti’s latest opus, La Loca, the story of Juana, the mad daughter of Spanish rulers Ferdinand and Isabella, wife of Philip the Handsome and mother of Charles V, especially written for the sparkling diva Beverly Sills then in the twilight of her singing career. I panned the opera as “dreary recitative unrelieved of its pall of permanent gloom.” And followed that saying, “Curiously, the orchestra occasionally drifts into noticeable strains of Vietnamese operetta, while no appreciable use is made of Spanish themes other than some corny castanets.” Of course, I had not written “Vietnamese!” Some typesetter or editor had changed it, and two days later they published a correction, to “Viennese.” (One of my favorite anecdotes from my writing career.)

Lyric Opera of Orange County

Okay, now I’m ready to address Lyric Opera of Orange County’s latest production, The Menotti Radio Hour, comprising two shorter works on a double bill. There were three performances over one weekend, and we attended on Saturday afternoon, Oct. 26. The conceit here is that we are in a live radio studio (KLOOC) and we witness the comings and goings of the artists, their outfits, the cigarettes and drinks they consume, the little jealousies, disagreements and gestures of affection among them, the actions of the Foley man for the sound effects off to one side, the announcer at his desk. It’s not a totally original idea: see The 1940’s Radio Hour. But in Menotti, we (illogically) hear the sharp tap of the ladies’ high heels on an uncarpeted floor, which could well have been picked up by the microphones.

Interestingly, the first-act piece, The Old Maid and the Thief, originally was commissioned by NBC in 1939 as the first opera ever written for radio. The composer was 28. Menotti created a stage version of it that premiered two years later and helped establish him as a successful American composer. It tells the charming tale of a handsome beggar who appears in a small town at Miss Todd’s door, announced by her servant Laetitia. The era, long before “women’s liberation,” determined that a woman’s worth was primarily measured by her relationship to men—father, husband, sons—and the opera depends on that assumption. In order to keep Bob around, as a possible future husband for one or the other of the two women, they house him, feed him, and give him money. “A hungry man is easily bent,” they say, and though he’d planned to get back on the road again, “even ideals listen to reason.”

Interestingly, the first-act piece, The Old Maid and the Thief, originally was commissioned by NBC in 1939 as the first opera ever written for radio. The composer was 28. Menotti created a stage version of it that premiered two years later and helped establish him as a successful American composer. It tells the charming tale of a handsome beggar who appears in a small town at Miss Todd’s door, announced by her servant Laetitia. The era, long before “women’s liberation,” determined that a woman’s worth was primarily measured by her relationship to men—father, husband, sons—and the opera depends on that assumption. In order to keep Bob around, as a possible future husband for one or the other of the two women, they house him, feed him, and give him money. “A hungry man is easily bent,” they say, and though he’d planned to get back on the road again, “even ideals listen to reason.”

Now, Miss Todd is not a rich woman, although she’s a highly prominent one—on every church and civic community board, the very model of an upright, respectable citizen. So the two resort to petty theft, and even breaking into a liquor store, to hold onto their prize. They have to keep him as a virtual prisoner in the house because there are reports of a thief in town, and he is—at least to them—the primary suspect. Miss Todd’s close friend, another spinster Miss Pinkerton, is the town busybody whose suspicions are aroused by the continued presence of Todd’s visitor in the house. The anti-moral of the story is the ironic conclusion, “The devil couldn’t do what a woman can—Make a thief out of an honest man.”

As an old Menotti hand, this was a treat for me. I knew the score from a recording but had never seen it on stage—even semi-staged as here. The performers did it proud and extracted much laughter from the audience—Leeza Yorke as Miss Todd, Christine Oh as her sidekick Miss Pinkerton, Lauryn Jessup as Laetitia, and Christopher Walters as Bob. J. Bradley Baker did the honors on the piano.

Composed as a modern opera buffa for all its comic potential, this one-act opera continues to delight performers and audiences. It’s especially popular at music schools for its ingratiating, accessibly written roles, where generally the full orchestra version of the score would be employed. It also summons up the spirit of comic opera in the sense that pretensions are exposed and hypocrisy unveiled. Respectability is tenuous at best, and inconvenient when urgent passions of the heart take hold. In his gentle manner, Menotti satirizes small-town social mores and the widespread inclination toward poking noses in other people’s private affairs. At a time when no public voice could be heard for the queer community, this was about as far as Menotti could go in terms of social criticism. In fact, the opera stems from a visit he made with his partner to Barber’s family, where he found gossip, scandal, and backbiting in what on its public face seemed a quaint little town.

A descent into madness

The Medium, a 1946 one-act that usually is paired with a second opera (Menotti’s The Telephone, frequently), was also made into a radio production, as well as a live TV presentation and a 1951 noir film starring Marie Powers as Madame Flora and Anna Maria Alberghetti as her daughter Monica. The same artists who appeared in Old Maid also sing in the second act: Christine Oh as Monica, Lauryn Jessup as Mrs. Gobineau, one of the medium’s clients at her weekly seance, Christopher Walters as Mr. Gobineau, Leeza Yorke as another client, Mrs. Nolan, and introducing Christine Marie Li as Baba, the medium. The opera has a mute actor, Toby, “a little starving gypsy, roaming the streets of Budapest,” according to Baba, whom she rescued from hunger and adopted. He and Monica form a relationship that is close and loving, perhaps veering on romantic, which looms increasingly threatening as Baba descends into madness. But this character, since he has no speaking role, is not in the broadcast studio.

Recently we have seen an efflorescence of directorial choices to present a work through the medium of another form of technology (a recent Madame Butterfly here staged as though on an early movie sound stage where the audience gaze is mainly directed to what they see on the screen over what they see on the stage). Here the conceit of the radio studio, which was unobtrusive and even authentic-looking in Old Maid, broke down. The character of Baba (the new singer to the cast) was announced even in the dialogue of Act 1 by her absence—where is she? why is she so late? will she come? will another singer have to fill in for her? So when she does arrive for Act 2 we already have a negative impression of her, and the other singers tend to avoid her, abandoning her alone in the studio at the end once their own parts are over. She acts like the diva, she smokes, she drinks, she has her hands all over people, and is especially jealous of the evident affection between Christine Oh and—not Toby, who is only referred to and doesn’t appear on stage—but the Foley man, Milton Salazar. In this production, the focus is overwhelmingly on Ms. Li as the performer, not the protagonist and title character, Baba the medium. Where we might have had empathy with this older woman going mad from her own life of deceit and cheating her customers, she is reduced in stature to a pathetic hallucinating drunk.

In her climactic aria “Am I Afraid?” I was struck anew by her revelations. By 1946, World War II is barely over, and we don’t even know exactly where this opera takes place—it’s enveloped in a kind of tragic Central European fatalism. But she recalls scenes from her “young days,” perhaps in the aftermath of World War I (audiences in 1946 no doubt could relate to more recent holocausts), and we must, we simply must take account of the horror and suffering she has gone through. She is a sympathetic character:

Can it be that I’m afraid?

In my young days I have seen many terrible things!

Women screaming as they were murdered,

And men’s hands dripping with blood,

And men haunted by knives.

And little grotesque children drained

White by the voraciousness of filth,

And loathsome old men insane with vice,

And young men with cankers crawling

On their flesh like hungry lizards.

This I’ve seen, and more, and never been afraid.

As in the first opera, the singing here is magnificent, though again, it’s just the solo piano for accompaniment. LOOC recruits top-notch local talent with a good deal of stage experience. The feisty company—Orange County’s only opera company—chooses its repertoire thoughtfully, and I appreciate their sense of proportion and modesty.

The stage direction is by Jen Stephenson, and the music director is pianist J. Bradley Baker. Diana Farrell, executive director of the company, designed the stage. The technical director and props guy is Grant Cornish. Raul Valdez is the stage manager. Gabriel Cazaras played the Station Manager reading the announcements and setting the scene (a little soft-spoken situated as he was way at rear stage). An excellent system for supertitles gave us the entire text in both English and Spanish. The venue was the OC Music & Dance Black Box Theatre in Irvine, an intimate space that fit the program perfectly.