Election campaigning closed in Mexico on Wednesday night with left-wing presidential front-runner Andrés Manuel López Obrador promising a “new phase of transformation” in the country.

López Obrador is expected to win Sunday’s vote, with the latest polls putting him at 49 percent, comfortably ahead of his rivals: the right-wing National Action Party’s Ricardo Anaya with 27 percent and more centrist José Antonio Meade on 21 per cent.

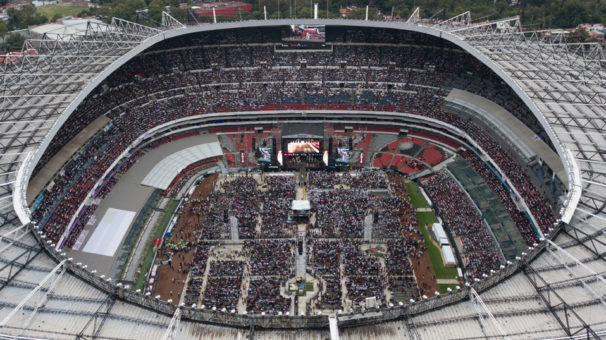

Thousands of supporters gathered in Mexico City’s Aztec Stadium for a concert and live performances to mark the end of a bloody campaign which has seen the assassination of over 100 candidates and journalists. But López Obrador promised a “peaceful transition” which will root out corruption and tackle inequality in the country.

“Nobody be scared of the word radical, which comes from the word ‘the root.’ And it will be a transformation that gets at the roots.

“We are going to end this cancer that is destroying the country. We are going to destroy corruption,” he told the crowds.

“I am the oldest candidate, but the young people, with their rebelliousness, imagination, and freshness, know that we represent the new. The young people know that we represent modernity.”

Though he is expected to win on Sunday, López Obrador says that it will not be an easy time ahead for his administration. There is a corrupt and “rapacious minority” of business executives, he says, who oppose him because they know they will have to “stop stealing” if he wins.

Widely popular among Mexico’s poor and working class, López Obrador, who was Mexico City mayor from 2000 to 2005, has long been viewed with fear by the many in the economic elite—a class that has had tight historic connections with the ruling political parties that López Obrador has lambasted as corrupt.

When he first ran for president in 2006 on promises to “put the poor first,” opponents likened him to then-President Hugo Chavez of Venezuela and launched a campaign branding him “a danger for Mexico.” Fierce opposition from business groups—along with what was believed by many to be widespread vote-tampering—may have cost him an election decided by a razor-thin margin.

His second run in 2012 saw López Obrador moderate his proposals somewhat, but once again he came in second. This time he has sought to be even more cautious, though at the beginning he did not hold back from attacking his critics.

López Obrador announced he would review and possibly reverse business-friendly reforms pushed by current President Enrique Pena Nieto. He has alarmed investors by saying he would scuttle a multibillion-dollar airport project on the capital’s outskirts, drawing the ire of the likes of Carlos Slim, one of the world’s richest men and a partner in the construction of the new terminal.

More recently, though, the candidate softened his stance, saying it’s not necessary to scrap the airport and suggesting instead that it be built entirely with private capital.

He has surrounded himself with economists with mainstream credentials such as Gerardo Esquivel, a Harvard PhD who has consulted for the United Nations and the World Bank. Esquivel is one of those tasked with easing fears among the entrepreneurial class.

“What is being proposed is to seek a better-adjusted balance between the activities of the state and the market,” Esquivel said. “What we learned in these years is that the retreat of the state from economic activity and leaving everything to the market caused mediocre economic growth and poverty.”

López Obrador promises there will be no expropriations or nationalizations, and says reviews of contracts under a planned reform of the state-owned energy giant, Pemex, would seek only to guarantee they were not won through corruption.

So far, López Obrador’s huge lead hasn’t led to a major market loss or precipitous decline of the peso, though the currency has slumped over other concerns, notably contentious trade negotiations and tariff disputes with the U.S., Mexico’s chief trading partner.

Alfredo Coutino, Latin America director for Moody’s Analytics, said the relative stability suggests markets have already baked in the possibility of a López Obrador presidency and are betting that market and institutional counterweights will check his power.

“If he were seen as a real threat,” Coutino said, “I think the markets would be moving very strongly and we would be seeing investment decisions postponed or withdrawn.”

This article features material from Morning Star and the Associated Press.