WASHINGTON – Employer associations are predicting a raise in the federal minimum wage will cause employers to lay off workers.

According to a new study, this is a false alarm.

The analysis was done by four economists. It shows the minimum wage hikes that 18 states and Washington, D.C. have enacted in the past three years have raised the pay of the lowest-paid workers without cutting the numbers of jobs or hours they work.

The analysis was published in early December by Sandra Black, Jason Furman and Wilson Powell, members of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors, and by University of Miami economist Laura Giuliana.

Minimum wage foes, led by the lobbies for restaurants and retailers – including Andrew Puzder, President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee as Labor Secretary – contend a minimum wage hike would cost jobs.

Actually, every time raising the minimum wage has been suggested over the years, employer groups pull out this claim. It has never been true.

The federal minimum wage, $7.25 an hour, has not risen in a decade, and many leisure and hospitality workers work for the “tipped minimum” of $2.13 hourly, which hasn’t increased in more than 22 years.

However, many states and 60 cities have raised their minimum wages, and the four economists studied the impact of doing so. They looked particularly at the impact of the wage hikes on the leisure and hospitality industry, which includes bars and restaurants. Federal data show that industry had 15.6 million workers in November – 34,000 more than a year before.

But the average leisure and hospitality worker toiled for only 26.2 hours weekly – unchanged from November 2015 and the lowest among all sectors. That average worker earned $394.57 a week in November, dead last among all the major sectors and more than $160 weekly behind the next-worst sector, the retail trade. The average paycheck for leisure and hospitality workers in November was $15.46 more than the prior November.

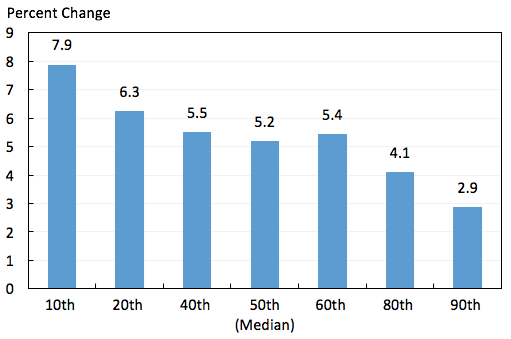

The poorest workers gained the most from the minimum wage hikes, the Obama CEA economists reported. While median average hourly earnings grew 1.4 percent for all workers since 2012, the median for the 10th percentile workers – the lowest-paid – rose 7.9 percent in 2014-15 alone, the fastest growth since 1968.

“Minimum wage increases implemented over the past three years by 18 states and the District of Columbia have contributed to substantial increases in average wages for workers in low-wage jobs, helping to reverse a pattern of stagnant or falling real wages in the preceding years,” they said.

“Moreover, this has occurred without any sign of an impact on employment or hours worked. As a result, average wages and weekly earnings for those who work in the lowest-paid jobs are at least 6.6 percent higher in these states than they would have been in the absence of these policy changes, based on a conservative” calculation.

Meanwhile, “employment in the leisure and hospitality industry follows virtually identical trends in states that did and did not raise their minimum wage. Moreover, employment in this low-wage industry grew somewhat more quickly than employment in the private sector overall,” the economists reported.

“This finding is consistent with a well-established empirical literature in which minimum wage increases are often found to have no discernible impact on employment. It is also supported by economic theory. In fact, when employers have sufficient market power” to unilaterally set wages “below what would prevail in a perfectly competitive market, there is scope for a higher minimum wage to raise both wages and employment,” they said.

In the states and D.C. that raised their minimum wage, “the average minimum, weighted by the number of private sector workers in each state, rose from $7.66 in December 2013 to $9.34 in October 2016 – an increase of 22 percent,” they added.

“In contrast, in 22 states, the minimum wage has not risen at all in the years since the last federal increase. And of this group, only one state has a wage floor that is above the federal minimum of $7.25,” they noted.

The economists used federal Bureau of Labor Statistics data for the leisure and hospitality workers because they’re “most likely to be affected by minimum wage policy.”

“As of December 2013, the typical leisure and hospitality worker earned $9.25 per hour – roughly the 17th percentile of the national wage distribution – and nearly half of these workers earned an hourly wage less than 120 percent of the minimum wage in their state.”

When previously enacted state minimum wage hikes started to kick in in 2014, the leisure and hospitality workers’ pay started to shoot up, the economists said.

“In states that took action, the average industry wage grew by 14.2 percent between December 2013 and October 2016 – resulting in wages that were 14.8 percent higher than they would have been had the downward trend prior to January 2014 continued.

“By comparison, the average wage in the comparison group of states” – the ones that didn’t raise their minimum wages – “grew by 7.2 percent and was only 4.5 percent higher by October 2016. And by the same month, the difference in weekly earnings growth for the leisure and hospitality workers in the minimum wage states was even more: 16.4 percent since 2014, compared to 4.7 percent in the other states.

“Raising the wages and incomes of working Americans is one of the country’s greatest policy challenges,” and an Obama administration goal, the economists stated. “The analysis presented here, along with a larger body of economic research, provides further support for the view that moderate minimum wage increases can substantially boost earnings for low-wage workers with little or no impact on employment,” they concluded.