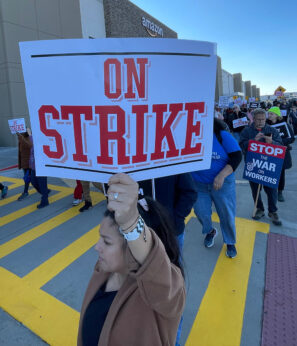

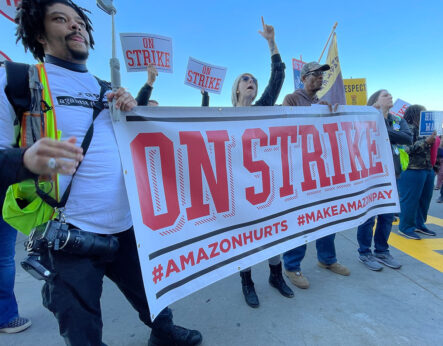

ST. LOUIS — On Black Friday, 2022, Amazon workers went on strike over brutal working conditions in 30 countries across the world. Saint Louis’s Amazon Fulfillment Center 8 would not be left out.

Black Friday, the day following Thanksgiving, is the USA’s largest shopping day of the year. It has been so for decades, generally marking the unofficial first day of holiday shopping.

However, in recent years Black Friday sales have begun earlier and earlier in the morning. Ten years ago, it was not uncommon to see lines of consumers waiting mirthfully in the cold outside of retailers at 2:00 am, hoping for a chance to buy one of five televisions marked at half off.

In the years since the retailers have gradually adjusted their hours to be the first open. In the American spirit of consumerism, Black Friday sales began being extended all the way through the following weekend and beyond. During all this hype, fanfare, and the added activity during the holiday season, little time has been considered for those who make Black Friday happen: service workers.

It was when Black Friday hours stretched far enough to begin on the evening of Thanksgiving itself that the level of criticisms began to rise to the point where they had to be heard. Workers that unload the trucks, receive goods, drive the forklifts, stock the shelves, work the register, help with makeup, answer questions, process warranties, de-escalate conflicts, collect carts, straighten merchandise, unlock secured goods, and clean the aisles have been expected to work mandatory overtime and even sacrifice their own holiday time with family for a day of consumerist bedlam.

The lockdowns associated with COVID-19 collectively gave workers time to consider their own working conditions and work/life balance. Capitalism itself has been reconsidered by millions of American workers.

As a result, workers have shown a new exuberance for unionizing, refusal to accept substandard wages and conditions, and a willingness to go on strike. Starbucks had zero unionized locations in 2020, and now more than 250 locations have union recognition.

Fast food chains changed their narrative from “$15 per hour is impossible” in 2020 to posting “$15 per hour and paid today” in less than two years. Railroad workers have voted to strike, shutting down a third of all transportation of retail goods less than 3 weeks before Christmas.

Online retail giants like Amazon declared incredible growth and profits during the COVID-19 lockdowns, yet Amazon has doubled down on union-busting and ignoring workers complaints.

“Get up! Get Down! Saint Louis is a union town!”

Thirty minutes before the afternoon shift change on Black Friday, about 200 workers from the community arrived outside the massive Amazon facility in Saint Peters, Missouri, and started warming up. Amazon employs an astounding 1.5 million workers worldwide, of which around two-thirds are employed in the United States.

Every American knows someone who works or has worked for Amazon. It is no longer a secret that Amazon treats its workers without dignity. Documentaries like Truth Behind the Click (2014), films like Nomadland (2020), and books like Seasonal Associate (2018) and The Warehouse (2021) give incredible insight into Amazon’s working conditions, but none of this media hits home like a family member or close friend with a personal account of being dehumanized.

The crowd who showed up to support Amazon workers included members of unions like the Glazers, Painters and Allied Trades, Pipefitters, Teamsters, United Sheetmetal Workers, CWA, UFCW, SEIU, Machinists, and retirees from the Operating Engineers and the Insulators unions. The president of UAW Local 2250 was there.

Political and social justice organizations were also present: CPUSA, Democratic Socialists of America, Missouri Jobs with Justice, Saint Louis Workers Education Society, Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, and the Missouri Workers Center. The Missouri Workers Center has been the driving force behind the organizing efforts at Amazon in Saint Louis.

“Come on out. We’ve got your back! Come on out. We’ve got your back!”

The time for shift change is upon the crowd. At that point, dozens of Amazon employees walked off the job and joined in with the cheering and smiling workers outside. Some even took the bullhorns and led the chants. The atmosphere was jubilant. Handshakes and hugs were exchanged. Energy was high.

An hour after supporters first arrived, Amazon sent out one representative to clear away the elated gathering. He repeated, in a barely audible voice, that those without an ID badge needed to leave. One attendee supporting the workers told the man that she was sorry for Amazon putting him in such a position.

The exchange highlighted one of Amazon employees’ collective complaints about workers’ security. There simply is no sufficient security staff to protect the workers inside, should an actual malicious trespasser arrive.

“We are the workers, the mighty-mighty workers, fighting for a fair wage and unions for all!” the demonstrators chanted.

Warehouse workers unions are not new. The ILWU (familiarly known as “the dockers” or longshoremen), famous for refusing to load scrap iron being sold to Japan during WWII for the Empire’s war effort, organized warehouse workers as far back as 1937. In Saint Louis, Teamsters Local 688 organized warehouses half a century ago. So, how is Amazon different?

Worker turnover at Amazon is extremely high. Amazon’s employment methods are designed to keep seniority low. Signing onto work at a fulfillment center means entering into an agreement to work mandatory 50-hour work weeks. After two years, Amazon will begin to offer payoffs to workers to get them to resign. Amazon also relies heavily on seasonal workers and arguably makes its relationship with seasonal workers the standard for all employees. Visibly, Amazon’s plan is to keep workers miserable and uninvested, in hopes that they quit before long because it is historically workers with seniority and vested interest in the company that organize unions.

Unionizing is a threat to Amazon’s employment model of turnover. Workers who have entered into a bargaining agreement with an employer generally cannot be disciplined or terminated without just cause. A union contract means a grievance procedure, which means job security, workforce stability, and ultimately a massive eventual boost to seniority among the workforce.

“When workers rights are under attack, what do we do? Stand up! Fight back!”

Workers who have never been on strike, or possibly never been a union member, might not understand how non-union workers can call a strike. The National Labor Relations Act (1935) legalizes workers’ greatest weapon: the strike.

Workers do not actually need union recognition to strike, but it definitely helps. Existing unions have experience with filing an Unfair Labor Practice (“ULP”) with the National Relations Board that provides great protection from employer retaliation. The Act allows workers to strike, however, if the stated reasons are economical, the employer retains the right to try to replace the striking workers.

What made the Fight For $15 campaigns so dramatic and effective was the use of the ULP strike. Fast food workers walking off the job for a day caused major disruption and financial hardship, but the employers were unable to make a legitimate case for replacement. Starbucks workers, represented mostly by the Workers United Labor Union, have been using strikes to great effect against the corporation who has been refusing to bargain in good faith by delaying negotiations.

If you read the comments in any coverage of campaigns to organize Amazon workers, you might see some misguided advice like “go to school” or “get a good union job.” Warehouse positions have become “Mcjobs” in recent years as online shopping has exploded in popularity.

The public perception is that “robots do all the work,” and subsequently the labor becomes devalued. In reality, shipping/receiving/fulfillment is exceptionally fast-paced and labor-intensive.

A century ago, manufacturing jobs were misperceived as “unskilled,” yet those workers organized to become the United Auto Workers. The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) began with janitorial staff and “soda jerkers” in drug stores in the 1930s, then swelling with healthcare workers to become one of the largest labor unions.

Migratory workers in California formed the legendary underdog United Farm Workers (UFW) organized popular boycotts and successful international work stoppages. All of these unions mentioned, and countless others began as groups of workers that lacked respect from the public at large.

The organizing committee of Amazon Fulfillment Center 8 is known as “STL8.” It has not been made public whether the STL8 wish to become part of the Teamsters, UAW, Machinists, or whether they will become an independent union like the Amazon Labor Union of Staten Island’s JFK8. Regardless, these workers need all the possible support from their fellow workers to succeed. When they do succeed, society will be better for it.