On November 4, an assembly of Native people and others honored the great warrior for Indigenous rights, Dennis Banks, with a celebration of his life entitled the “Longest Walk” in Nashville. This was in memory of the protest march of 1978 that he initiated.

Dennis passed away on Sunday, October 29, at age 80, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. In Nashville, upon hearing the sad news, myself and others immediately decided to hold a memorial for this stalwart leader of the Native cause.

The memorial celebration was held at the Casa Asafran Community Center, which serves the city’s Latino populace. Among those sharing memories of Dennis was Lou White Eagle, Southern Cheyenne who in the 1970s led an Oklahoma chapter of the American Indian Movement (AIM) chapter, myself, and others.

Although this was a celebration of this prominent leader’s life, it was a very solemn occasion, for we were all very saddened at his passing. I received a call the preceding Sunday night from White Eagle that Dennis had left us.

The celebration began with the AIM Song by Eagle Nation, a local Native drum group. This was followed by a Memorial Song, a Victory Song, and a Traveling Song to ensure Dennis a good journey to the “Spirit World.”

I related how I had the opportunity to meet Dennis over the years at various gatherings and protests. The last time I talked with him was at the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota a little over a year ago. He seemed “fit as a fiddle” at the time.

White Eagle, who knew him much better than I, spoke of his humanity, level-headedness, and sense of humor. He said Dennis told everyone that no matter what happened, always “stay strong.”

An honor song was sung by local musician Kenny Mullins with lyrics comparing Dennis to other great leaders in Indian history. Mullins recounted that he met Dennis, when as a 14-year-old living on the East Coast he ran away from home to join AIM when the Movement held a conference in his area. He related that he actually stayed with AIM for about four days, after which they nicely said that his parents were probably worrying about him and made sure he got home safely.

White Eagle prepared a eulogy, which read, in part: “This is about a very special person in his own powerful and sacred journey among the black, white, yellow, and red races of people. This special person comes from the red nation of Indigenous human beings. This special person is a relative, friend, activist, teacher, lecturer, author, movie star, and a hero that walked and ran a very good path of commitment to many human beings.”

Among the many tributes accorded to Dennis, I read a document entitled, “A Presidential Proclamation of the Oglala Sioux Tribe of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.” This was issued by Troy Scott Weston, president of the tribe, proclaiming November 4, 2017 as “Dennis J. Banks Remembrance Day,” in recognition of his contributions to the struggles on Pine Ridge.

Dennis was a tireless fighter for Indigenous rights and represented what can be called the Old Guard of AIM, alongside figures such as Russell Means, Carter Camp, John Trudell, and Vernon Bellecourt—all of whom have now passed on but never hesitated to put their lives on the line fighting for the rights of Native people.

Dennis was Ojibwe, born on the Leech Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota in the government-imposed poverty that is the lot of the majority of this land’s Indigenous. Dennis was one of the founders of AIM, along with Clyde and Vernon Bellecourt, George Mitchell, and others. AIM started in 1968 to combat the brutal, racist police treatment of American Indians in south Minneapolis. From those beginnings, the Movement organized marches, protests, and takeovers in the quest for justice for the Indigenous. Along the way, Dennis met Russell Means, who was the director of the Cleveland Indian Center and later a frontline leader of the Movement.

Dennis took part in the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz, site of the infamous federal prison that was closed in 1963. He also led AIM in a takeover, in November, 1972 of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington, D.C. that became known as “The Trail of Broken Treaties.”

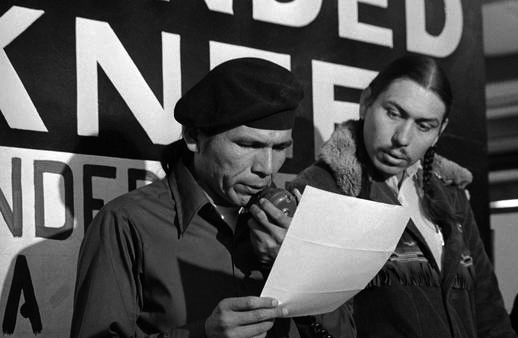

The most well known AIM takeover was that of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in February 1973, which was orchestrated by Dennis and Russell and other movement leaders. AIM was invited to the reservation by the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization (OSCRO) to assist in the struggle against tribal government corruption and racism directed against Native people in South Dakota. The Movement and its supporters held Wounded Knee in a 71-day standoff. Dennis and Russell Means were charged for their roles in the takeover, but after a trial of several months in St. Paul, a judge dismissed the charges on the grounds of prosecutorial misconduct on the part of the government.

Subsequently, in the 1980s, Dennis was incarcerated for 18 months for charges stemming from an AIM confrontation in Custer, S.D. that preceded Wounded Knee by a few weeks in 1973. He had avoided prosecution for several years as Gov. Jerry Brown refused to extradite him to South Dakota on the grounds that his life would be in jeopardy. After California elected a new governor unsympathetic to Native causes, Dennis was given sanctuary by the Onondaga Nation in New York.

Dennis was known for organizing cross-country walks to bring attention to the oppressive plight of Indigenous people. The first was the “Longest Walk” of 1978, which he initiated in response to eleven bills that sat in front of Congress which would have eliminated land and water rights on reservations across the U.S. This was 3,200 mile walk that began in February in San Francisco and reached Washington, D.C. in July of that year.

His last march, in 2016, dubbed the “Longest Walk 5,” was Dennis’ declaration of war on the drug epidemic afflicting so many reservations as well as domestic violence against Indigenous women. In fact, this struck home so tragically and personally as one of his grandchildren, Rose Downwind, died as a victim of domestic violence in October 2015.

This last caravan also focused on the many unsolved murders and assaults on Native women. It was recently reported that missing Indigenous women is the only demographic for which there are no statistics.

In his autobiography, Ojibwe Warrior: Dennis Banks and the Rise of the American Indian Movement, he recounts his episodic life in fighting for Indigenous rights. I read it several years ago and would recommend it for a further in-depth understanding of the Native struggle in the latter 20th century and the pivotal part played by AIM.

Our commemoration concluded with a renewed commitment to continue the great legacy imparted to us by the vision, activism, and leadership of Dennis Banks.