A third of the Amazonian rainforest is threatened by extreme pressure. For the last few years, the deterioration has intensified. The following is a special interview with Julia Jacomini from a publication of the Amazonian Network of Socioenvironmental Information (RAISG), which puts the latest data about the rainforest into perspective, in the first additions to the original document published in 2012.

Atlas: The Amazon Under Pressure was released on Dec. 8 by the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA). The document, the first version of which was published in 2012, includes a series of indicators that together represent an X-ray of the region’s current situation. The time period of the study, based on the majority of the statistics, is between 2000 and 2018 and includes different degrees of data classified as “pressures and threats” and “symptoms and consequences.”

As geographer and researcher Julia Jacomini explains, in an on-line telephone interview, “in the 2020 Atlas, we classify as ‘pressures and threats’ all infrastructural works, including roads and hydroelectric plants, extractive activities like drilling for oil and mining (including prospecting for precious metals and stones) and mixed crop and animal farming. We also have data we call ‘symptoms and consequences,’ like deforestation, slash and burn clearing, and variations in carbon density, which has been incorporated recently in the Amazon Web of Georeferenced Socioenvironmental Information (RAISG) analyses.

“In recent decades we have witnessed very rapid growth of pressures and threats and of the symptoms and consequences of human activities in the entire Amazon region. The first analysis in 2012 revealed what was already a complicated picture, now all these matters have become more acute. Unfortunately, not a single threat has ceased to exist. Now all threats are increasing.”

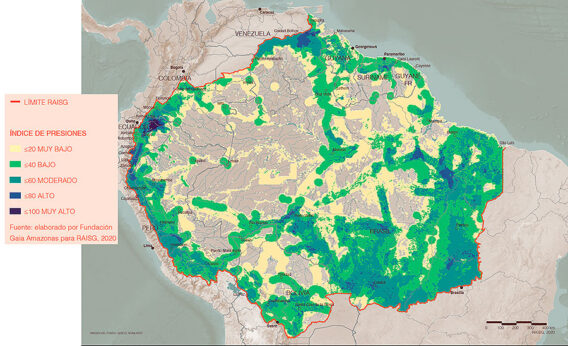

The document points out that, beginning in 2012, there was a resumption of the rise in deforestation that intensified between 2015 and 2018, when the size of the affected area tripled. “The final results show that, between 2000 and 2018, more than 500,000 square kilometers of Amazon forest were cleared, a territory the size of Spain. Among the main pressures leading to this deforestation is mixed crop and animal farming, responsible for 84% of the total,” according to Julia. “All these threats accumulate, leading to the current situation: 30% of the Amazon is under high or very high pressure. This means that apart from the evaluation of each theme separately, we attempt to make an integrated analysis of all the data.”

If, on one hand, the scene is far from hopeful, it has demonstrated that what has happened to the protected natural areas and Indigenous territories is an excellent indicator of what we have to do to protect the forest. “Almost 90% of the deforestation, in these last 18 years, occurred outside of Indigenous territories and nature preserves,” Ms. Jacomini emphasizes.

Julia Jacomini is a researcher with ISA and RAISG. She has a degree in Geography from UNESP-Rio Claro, specialized in Applied Geoprocessing at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, and has a Masters in Latin American Integration from the University of São Paulo. [Brazilian custom is to refer to individuals by their first name, such as “Lula” and “Dilma.”]

Julia Jacomini’s interview with IHU (Humanitas Institute, Unisinos)

IHU—Which indicators are studied and presented in Atlas: The Amazon Under Pressure?

Julia Jacomini—RAISG is a non-governmental network of organizations from six Amazonian countries. One of the great contributions of the publication of Atlas: The Amazon Under Pressure (2020) is to present a regional analysis that extends beyond the politico-administrative borders of those countries. Usually, we content ourselves with studies on a national scale, whereas a study like this one by RAISG provides an integrated, Amazonian standpoint.

RAISG began in 2007, ready to provide this kind of regional analysis, and published the first Atlas: The Amazon Under Pressure in 2012. Subsequently, some maps were published, but more thorough analyses were only published in 2020, in the document we are discussing. In this context, it was important to make comparisons, but from then until now some new themes were incorporated in the analyses and new methodologies were developed. For that reason, any comparisons have to be made carefully.

When it comes to pressures and threats, we consider works of infrastructure, like highways and hydroelectric plants, extractive activities such as drilling for petroleum and all sorts of mining (including riverine prospecting) and, finally, mixed crop and animal farming, all incorporated in the 2020 Atlas.

Aside from the pressures and threats, we have data we call “symptoms and consequences,” namely, deforestation, burn-offs, and variations of carbon density, the latter incorporated for the first time in the RAISG analyses.

IHU—What are the main weaknesses of the current Amazon region?

Julia Jacomini—I want to start with the data about deforestation since it is information produced by RAISG. Each of the six countries produced its official statistics, but if we were to put them together, the periodicity and the methodologies are not contradictory. RAISG developed its own methodology, beginning with an analysis of the use of the soil, so the data may be similar to that divulged by INPE (National Institute of Spatial Studies), for instance.

The base year is 2000 and we continued analyzing the data until 2018. During this period, the largest proportion of the historical series is in 2003. Beginning that year, we have a decline in deforestation, whose smallest numbers are in 2010. As of 2012, the numbers begin to increase again, but the most rapid acceleration is between 2015 and 2018 when deforestation triples. The final results demonstrate that between 2000 and 2018 more than half a million square kilometers of rainforest were demolished, an area the size of Spain! Among the main pressures leading to this deforestation are land cleared for crops and pasture, responsible for 84% of the total.

Against the background of this desolation, there is something noteworthy: the effect of the Indigenous territories and protected natural areas. Approximately 90% of the deforestation, in the course of these 18 years, took place outside these two areas. This shows that such territories are important barriers and also highlights the importance of the activities of the Indigenous peoples and traditional communities in maintaining the surviving forest. At the same time, although they are important barriers, these territories are being ceaselessly threatened.

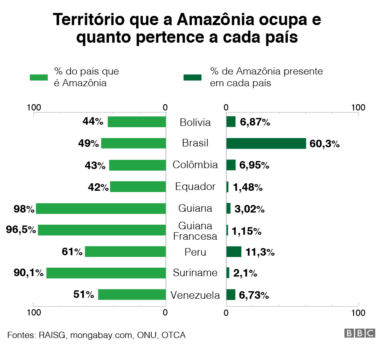

This tendency to destroy the Amazon forest is being pushed, in great part, by Brazil. This is because the country has more than 60% of the Amazon territory, but also because Brazilian deforestation is moving ahead faster than any other country, which raises the average of the region as a whole.

IHU—What are the indicators that the Amazon forest is at risk and deteriorating?

Julia Jacomini—There are other indicators than deforestation. In the case of cutting and burning the vegetation, we did an analysis from 2001 to 2019, showing that 13% of the Amazon had been affected by fire. This equals an area the size of Bolivia, more than a million square kilometers. Although we know that just one fire will not cause deforestation, we observe that there are various repetitions of fires, year after year, and these consecutive burns can lead to a great deterioration of the ecosystems and provoke deforestation.

The country in the Amazon region most devastated by slash and burn agriculture happens to be Bolivia, with 27% of its Amazon territory stricken by fire. Next comes Brazil. This helps us understand that, depending on the theme, some threats are more serious in some countries than others.

Mining

Mining is another very serious issue in the Amazon which affects 17% of the region’s territory and is present in all the countries touched by the rainforest. However, 90% of all such activity is concentrated in four nations: Brazil, Venezuela, Guyana, and Peru. Brazil is the country that has the greatest interest in extractive areas with 75% of all such areas located within its borders. This does not imply that all these areas are already being exploited.

Prospecting is another subject presented in this study. First, it is necessary to stress that this kind of data collection is difficult, mostly because it is an illegal activity and thus has no official information source. Data collection via satellite is made difficult by the number of clouds in the Amazon and also because prospecting is a very itinerant activity, with sites that are activated and deactivated surreptitiously, according to the advance of inspectors. There is still a lot of gold mining that takes place in riverbeds with light wooden rafts that are used to move explorers and equipment from place to place. Therefore, the data we present in the report are classified as “the best information available,” which falls far short of substantive.

In the 2020 Atlas, we collected evidence of more than 4,400 activities of illegal prospecting in the Amazon region, of which more than 87% are actively exploiting available resources at their own risk and to the detriment of the region’s natural resources. More than half of these prospecting locales are in Brazil. The runner-up is Venezuela, which accounts for 32% of this total although only 6% of the Amazon territory falls within that country’s borders. Both strip mining and panning for gold and gemstones represent great threats in both Brazil and Venezuela.

IHU—What is going on with oil drilling in the Amazon?

Julia Jacomini—In Brazil, there is little oil drilling, but in Ecuador, the situation is very grave. From a general point of view, drilling lots occupy 9.4% of the Amazon area, and most of this is in the so-called “Andean Amazon” in territories of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Ecuador is the country with the greatest percentage occupied in this kind of activity, 51.5% of it in Amazonian territory.

When it comes to petroleum, there are significant impacts caused by spills. Much of the activity characteristic of this pursuit involves the construction of infrastructure. It is always important to think of these pressures and threats with an eye to associated requirements, because all these explorations, including mining and generating hydroelectric power, are associated with the building of roads, which are the great vectors of deforestation. A region that is impacted by petroleum and mining will also have to deal with subsidiary needs for roadways, railways, and powerlines and, especially in the Amazon, with construction of hydroelectric facilities.

All these threats mount up, leading to the 30% of the Amazon that is currently subjected to high or very high pressure. This means that, as well as evaluating each theme separately, we attempt to make an integrated analysis of the data. The same region may be subject to more than a single pressure or threat. It follows then, that a completed roadway has more impact than one that is still in the planning stage. Thus, our analyses must also take into account the weight of each theme, depending on the stage of the work and activities, as well as how such activities are superimposed.

Returning to the problem of Ecuador, this is the most dramatic case of the pressures and threats in relation to petroleum production. According to RAISG analyses, 88% of the Ecuadorian Amazon is being affected by some kind of pressure, from the lowest to the highest, all of them in active process.

IHU—What is the importance of thinking about these themes as connected?

Julia Jacomini—The Amazon region is very large, and the realities of each nation involved in the study are quite different, so it is fundamental that we think in a connective way. Even when we consider the data within a single country, we see that there are regions more affected by one or another activity. However, when we analyze the data in an integrated way, we get a more complex and realistic image of the situation, that helps us to understand the process of accelerated deterioration. But at this moment we have highlighted the problems of mining, deforestation, and the burn-offs as the great threats that are rapidly encroaching on the Indigenous territories and the environmentally protected natural areas that, while they are important barriers of contention, are becoming increasingly fragile.

In Brazil’s case, the illegal prospecting on Yanomami Indigenous Land, apart from being a big threat in relation to environmental impact, has brought an additional risk to bear, as the prospectors are contaminating the local populations with the COVID-19 virus. We had high contamination rates as a result of the invasion of prospectors transmitting the virus.

IHU—By the way, how has the global COVID-19 pandemic impacted the Amazon region?

Julia Jacomini—We have been working on consolidating this data on a regional scale. The difficulty we have had to face is how this data is being employed by the countries in question when it comes to differentiating the Amazonian populations. Also, sometimes the countries’ data do not include specific information about the Indigenous populations.

The effect of the pandemic has been very problematic in the Amazon region, particularly because of the difficulty of isolating when these territories are very fragile and being subjected to invasion, as is the case with the Yanomami. In Brazil, there have been cases where frontline health workers themselves are vectors of the virus within the villages, especially because of the systemic weakness of the environmental and government agencies charged with the protection of the Indigenous peoples, with ever fewer teams and resources, with the result that supporting the traditional populations has become increasingly difficult. Venezuela has also carried out a COVID-19 survey in its Indigenous territories but as yet we have nothing consolidated on a regional scale.

IHU—Putting things into perspective, relative to the first Atlas produced in 2012, what has changed from then to now?

Julia Jacomini—First, the methodology, and that has had an impact on the analyses. That is why, in the current edition, our area of analysis has widened. Before, we were considering only the Amazon basin and its political and administrative aspects. Whereas now we are contemplating the headwaters of the Amazon tributaries. This means that we are analyzing the Andean region, as well as the forested Bolivian Chaco and the Cerrado, an area of dense, herbaceous vegetation and short twisted trees in the high plains of central Brazil.

Unfortunately, none of the threats have disappeared. Rather, they are in an expansive mode. As for the comparisons, it is important to emphasize that, since the last edition, published in 2012, the RAISG analyses have improved in terms of methodology, information access, and cartographic precision. As a result, it is possible to find some disparities in relation to the 2020 data. That is why the temporal comparative analyses are merely referential.

The following data, in quotes, are citations extracted from the 2020 Atlas: The Amazon Under Pressure.

Roads

“The density of roads in the Amazon, calculated from the extension of roads and territory, grew by 51% between 2012 and 2020, growing from 12.4 square kilometers to 18.7 square kilometers. The countries that led this expansion were Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela.”

Hydroelectricity

“In 2012, 171 hydroelectric plants were registered as functional or under construction within the RAISG limits for the Amazon, a number that does not include the headwaters located in the Andes and in the southeastern region of the Brazilian Amazon. In 2020, this number had grown by 4%, reaching a total of 177 hydroelectric facilities. Their proliferation rate was 47%, from 51 in 2012 to 75 in 2020.”

Petroleum

“Between 2012 and 2020, the Amazon region registered 13% growth in the number of drilling sites (from 327 to 369 in 2020). However, in the same period, the use of land by petroleum extractors diminished by 350,184 square kilometers. This does not necessarily mean that the petroleum industry is shrinking in the Amazon region as the reduction is related to lots listed as potential extraction sites which, when they have no lessees, are removed from the official database.”

Mining

“In the period from 2012 to 2020, the Amazon region registered an increase in the number of mining zones (52,974 in 2012 to 58,432 in 2020). However, there was a reduction in the territorial lands occupied (from 1,628,850 square kilometers in 2012 to 1,322,600 square kilometers in 2020), which does not necessarily mean that there was a diminution of such activities in the Amazon region.”

Deforestation and burn-offs

“The analytic methodology was improved from 2012 to 2020, invalidating direct comparisons. However, the following information was highlighted and discussed in the preceding interview.”

Deforestation

“Although 2003 continues to be the worst year for Amazon forests since 2000 with a total loss of 49,240 square kilometers, deforestation has accelerated since 2012, after reaching the minimum 2010 (17,674 square kilometers). The annual area lost tripled between 2015 and 2018. In 2018 alone, 31,269 square kilometers were deforested in the entire Amazon region, the largest yearly deforestation since the 2003 peak.

“Between 2000 and 2008, the cumulative loss of forest native to the Amazon region was 513,016 square kilometers, a loss equivalent in size to the total landmass of Spain, as we have said before, or 8% of the total area of 6.3 million square kilometers of rainforest that existed in 2000.

“The regional reality can be different from the national in each of the Amazon countries. The tendencies described above as Amazonian are strongly determined by the Brazilian situation which contains 61.8% of the Amazon territory. Outside Brazil, Bolivia and Colombia are the countries that have most closely imitated these tendencies in recent years, with a total deforestation of 425,051 sq. km. (Brazil), 31,878 sq. km. (Bolivia), and 20,515 sq. km. (Colombia). The other RAISG member countries have not exhibited clear tendencies of growth or diminution.”

Slash and burn damage

“Around 13% of the surface of the Amazon region burned, at least once, since 2001; in all, 1.1 million square kilometers were affected. This area is comparable in size to the whole of Bolivia, which, coincidentally, is the country most affected by the phenomenon, with up to 27% of its Amazonian territory subjected to burns. On average, each year since 2001, 169,000 sq. km. of land were burned in the Amazon region, 26,000 of them inside the Protected nature areas and 35,000 inside Indigenous lands.”

IHU—In a global warming scenario, what could be the consequences for life on the planet if the deterioration of the Amazon region is not immediately braked?

Julia Jacomini —The consequences are already happening, for example, in the case of the annual burn-offs. The Amazon region has some burns that are considered natural in the dry season, when part of the vegetation burns, nourishing and strengthening the forest soil. We have observed that the dry seasons have become longer and longer. So climate changes are not something in the future, they are here now. When the dry seasons last longer, so do the fires, growing increasingly severe and difficult to control, as we have seen the last two years, both in Brazil and in Bolivia. Even though it is a distinct ecology, we have the example of what occurred in the Pantanal this year, because these drought conditions make these ecologies increasingly vulnerable.

In the long term, we have an intensification of all these processes and the impacts that the loss of biodiversity brings to the Indigenous populations and traditional communities, whose lives are very integrated with nature, affecting their ability to adequately manage their territories. What is more, the environmental devastation impacts the way they organize culturally and the way they live.

IHU—Is there anything else you want to say?

Julia Jacomini—It is fundamental to underline the importance of strengthening this vision of the Amazon region in an integral way. That is why it is important that we strengthen the links among Amazonian countries to combat the accelerated advance of the factors we have been discussing. It is necessary to consider the Amazon region in its entirety rather than on a country by country scale.

Translated for People’s World by Peter Lownds, Dec. 18, 2020.