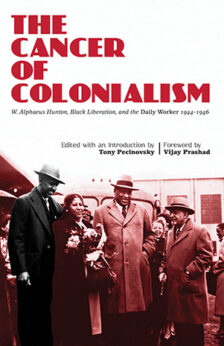

People’s World continues its interview series with authors of the latest books from International Publishers. In this edition, we talk with Tony Pecinovsky, author and editor of The Cancer of Colonialism: W. Alphaeus Hunton, Black Liberation, and the Daily Worker 1944-1946.

Q: This is the third book you’ve had in as many years dealing with different aspects of and personalities in Communist Party USA history. Can you tell us a bit about how the idea for a book on Alphaeus Hunton came about?

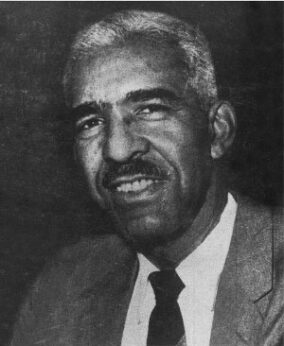

A: Well, I have been fascinated by Alphaeus Hunton’s life since first beginning research on Let Them Tremble, my collection of short Communist biographies. He was such an important figure in what is now called the “long civil rights movement.” His activism spanned from the mid-1930s Popular Front through the late 1960s Civil Rights and Black Liberation era. He was a central figure in groups like the National Negro Congress, the Council on African Affairs, and the Civil Rights Congress.

A: Well, I have been fascinated by Alphaeus Hunton’s life since first beginning research on Let Them Tremble, my collection of short Communist biographies. He was such an important figure in what is now called the “long civil rights movement.” His activism spanned from the mid-1930s Popular Front through the late 1960s Civil Rights and Black Liberation era. He was a central figure in groups like the National Negro Congress, the Council on African Affairs, and the Civil Rights Congress.

As a leader of the CAA, he also developed relationships with many of the then-emerging movements for national independence and their leaders in Africa. As a result, he forged links between those struggling for African American equality with those struggling for Black Liberation in Africa. He was essential to the forming of a cross-Atlantic alliance to combat both colonial subjugation and Jim Crow.

Interestingly, due to the racist political repression he faced domestically, he spent the last 10 years of his life living in Africa in the newly independent nations of Guinea, Ghana, and Zambia, where he died in 1970. In contrast to the political persecution Hunton faced in his native United States, he was treated like a visiting dignitary on the African continent.

Yet, he seems to be largely unknown outside of the academic left—outside of those who have specialized in research of groups like the CAA. Further, he has often been eclipsed by his better known peers Paul Robeson and W.E.B. Du Bois, his two closest co-workers and friends at the CAA. Of course, this isn’t Robeson or Du Bois’ fault; they are just better known and studied more often.

Q: Why is that? How have Hunton’s life and work gone unnoticed by a larger audience?

A: Until the publication of The Cancer of Colonialism, no book-length study of Hunton existed, aside from his wife Dorothy Hunton’s excellent, self-published, out-of-print biography Alphaeus Hunton: Unsung Valiant, which has just been reprinted by International Publishers. This seemed odd to me.

Obviously, there are hundreds of volumes on Robeson and Du Bois. Hunton is mentioned, often in passing, in these volumes. He is – sometimes more, sometimes less – mentioned in volumes on African American links to the global movements for African independence. Penny M. Von Eschen’s Race Against Empire, John Munro’s The Anti-Colonial Front, and Lindsey Swindall’s The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World, are excellent examples that place Hunton’s activism squarely into the narrative as a central figure.

Yet, no in-depth study of Hunton, his life and work, existed. So, I sought to fill this gap in the historiography, to provide a book-length review of Hunton’s political life, while also republishing his Daily Worker columns.

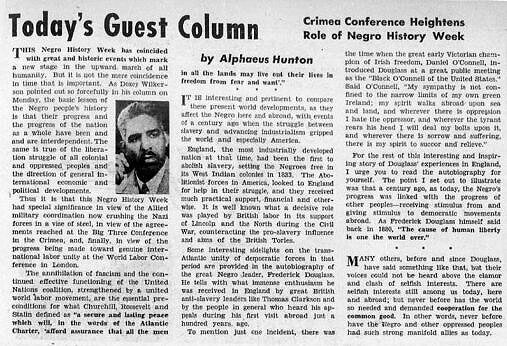

Since Hunton had been marginalized, I felt it was important for him to speak for himself. His Daily Worker columns allow him to speak for himself. They provide a window into his Marxist worldview. The Cancer of Colonialism actually takes its title from a comment Hunton makes in one of his Daily Worker columns. In the October 19, 1944, issue of the paper, he noted: Of all the “social and economic ailments from which the world at present suffers…the cancer of colonialism is one of the gravest.”

Q: It’s clear that Hunton and the work of the National Negro Congress and the Council on African Affairs were in a lot of ways forerunners of the more widely-known Civil Rights Movement and national liberation solidarity movements of the 1960s and 1970s. What aspects of the NNC and CAA’s work impacted the movements that followed them?

A: To clarify, the NNC and CAA are also the forerunners of the Black Lives Matter Movement. Many of the issues the NNC and CAA addressed are—unfortunately—the same issues being addressed by BLM. I say unfortunately because the assault on Black lives today has led to the need for a movement like BLM, just as the assault on Black lives in the 1930s led to the need for a movement like the NNC.

The NNC and CAA organized pickets, protests, and marches. They lobbied in Washington, D.C., for an end to segregation in the U.S. armed forces. When appropriate, they used theatrics to garner public attention; for example, the NNC held public trials to convict “killer cops” of murder. The NNC was a mass organization with hundreds of coalition partners and chapters across the county almost exclusively focused on African American equality and workers’ rights. While NNC chapters did embrace other issues, such as the fascist invasion of Ethiopia, equality and workers’ rights were the main focus. As such, there was a close partnership with the then-emerging industrial unions affiliated with the CIO and with a growing Communist Party USA. It is this activism that led Alphaeus Hunton to join the CPUSA, which may also be a partial reason for his neglect by mainstream academia.

The CAA was not a mass organization; it was an education council. It published a regular newsletter edited by Hunton, New Africa, and later Spotlight on Africa. It organized conferences and petitions. It issued press releases, published pamphlets, and made a film about the racist barbarity of apartheid in South Africa. Often it would partner with the NNC, the Southern Negro Youth Council, the CRC, with various Communist-led CIO unions, such as Ferdinand Smith’s National Maritime Union, to mobilize pickets and protests. But it saw itself as an information provider that could build alliances with, for example, Broadway celebrities and stars to bring attention to the links between domestic Jim Crow and colonial subjugation. Of course, Robeson was a celebrity and lent his name and financial resources to the CAA, but it was Hunton who was responsible for the CAA’s day-to-day operations. He did the unglamorous grunt work.

I think the main thing that was lost with the marginalization and forced dissolution of the NNC, CRC, and CAA was their ties to an internationalist movement. While the 1960s and ’70s Civil Rights and solidarity movements weren’t solely domestic by any means, they also didn’t have the international ties or connections of the CAA or CRC. This was a strategic goal of the 1950s Red Scare—to confine the permissible boundaries of domestic civil rights within the boundaries of liberal Western capitalism.

Hunton’s CAA—as well as the NNC and CRC—refused to acquiesce to this constraining of permissible political boundaries. They refused to acquiesce to anti-communism. Hunton actively sought out and built alliances with world socialism. He sought to build what I call a “Red-Black alliance.” This was tantamount to treason as far as Washington was concerned. As a result, he had to be punished. Like their CPUSA comrades, Robeson, Du Bois, and Hunton were all marginalized to make way for groups more willing to confine their critiques of the civil rights problem comfortably within the bounds of liberal Western capitalism, groups more willing to acquiesce to anti-communism—from the left and from the right.

This narrowing of political discourse had a negative impact on the 1960s and ’70s movements for Civil Rights and Black Liberation. Still today, I think we have yet to recover. Ironically, it is precisely this aspect of the CAA’s work that activists should spend time pondering and rebuilding.

Q: There are a number of continuing themes in your edited volumes, among them Black Liberation and the struggle against colonialism and neo-colonialism. How does Hunton’s story fit within this thread?

A: In short, I think it is impossible to understand the domestic struggle for Black Liberation and colonial independence without Hunton and the CAA. Excluding Hunton and the CAA from the historical record is tantamount to the falsification of history, just as excluding the National Anti-Imperialist Movement in Solidarity with African Liberation, which was founded in 1973 and helped to lead the South African divestment movement, is also tantamount to the falsification of history.

That the CAA and NAIMSAL were both led by Communists complicates our discourses on the permissible boundaries of Civil Rights and Black Liberation. With the current attacks on Critical Race Theory—often by people who don’t even know what it is—coupled with Hunton’s longstanding neglect among historians, now is the perfect time to bring more attention to this history, to use it as a teachable moment, to complicate the historical record.

For example, Hunton didn’t spend six months in prison in 1951 because he was a bad person, because he had done something wrong. Hunton spent six months in prison because he refused to cower in the face of political repression, because he refused to sacrifice his belief in our inalienable rights as outlined in the Bill of Rights. This was a man of tremendous conviction and moral fortitude, unlike the political sycophants and charlatans who sent him to prison.

In fact, Hunton was marginalized precisely because he, and those like him, were effective organizers capable of building international alliances strong enough to embarrass Washington on a global stage. Hunton had to be marginalized because he was successful. This is part of that larger thread that goes back to Let Them Tremble and the collection of essays in Faith In The Masses—this idea that the ruling class responded to Hunton out of fear.

The ruling class was fearful of Hunton and what he represented: Black militancy comfortable with red allies. Their jailing of him was a reaction based on weakness, not strength. There was, in fact, a great deal of trepidation, a great deal of “trembling” going on within the ruling class during this time, as world socialism, which Hunton was aligned with, seemed to be ascending.

It is hard to imagine today, but from the post-WWII period until the mid-1970s, socialism really felt like it was on the way for humanity. One-third of the world was governed by Communist Parties. Another one-third of the world was in the throes of revolution and national liberation struggles often aided and led by Communists. Hunton, Robeson, and Du Bois—as well as the CPUSA—were domestic combatants in a global campaign for world socialism. And for a brief moment in time, they seemed to be winning. This is part of the larger thread that is woven throughout Let Them Tremble, Faith In The Masses, and now The Cancer of Colonialism. This is a larger thread others should pay more attention to.

As some have noted, the collapse of world socialism partly explains the decades-long retrenchment of the left and the ascendancy of the far right. Just as the threat of unionization will often compel concessions from the boss, on a global scale the threat of socialism compelled concessions from world capitalism. Among serious scholars, this isn’t even debated anymore. I recommend Gerald Horne’s White Supremacy Confronted or Kristen Ghodsee’s Second World, Second Sex, for examples. Hunton’s story is part of this thread.

Q: In the story of Alphaeus Hunton, we see the familiar use of anti-communism as a tool to discredit those who fight against racism and colonialism. Today, we still observe some right-wing politicians attempting to undermine support for Black Lives Matter and racial justice campaigns by labeling them Marxist or communist. Why do you think this same smear tactic has been employed again and again over the decades?

A: Unfortunately, it is still an effective, divisive tool, among some. As I note in The Cancer of Colonialism, anti-communism became the dominant repressive political ideology of the 20th century and was directly responsible for tens of millions of deaths. While the domestic Red Scare wasn’t deadly for most of its targets—like the massacre of at least one million Indonesian citizens in 1965-66—it had a profound impact on the permissible boundaries of political discourse. As a result, even moderate reforms—such as expanding Medicare to include vision and dental benefits, a hot topic today—are labeled “socialist” by some, thereby creating divisions that are exploited by the ruling class to weaken domestic support for what is taken for granted in other countries.

Fortunately, I think anti-communism is becoming less and less effective. Among many younger people, socialism isn’t a dirty word anymore. Many in the upcoming generations have known nothing but poverty wages, racist police brutality, endless war, and environmental destruction. Capitalism has been a complete failure their entire lives. They are exploring socialism, though the concept means different things to different people. I think Hunton would be heartened by this.

Q: Do you have plans for further research or work on Hunton? And what would you say makes the life and work of Alphaeus Hunton most relevant for activists today?

A: Well, as for the first part of the question: I hope to work on a Selected Correspondences of Alphaeus Hunton in the near to intermediate future. As you can imagine, Hunton corresponded with leaders of Black progressive organizations of the time, Robeson and Du Bois being the most prominent. But he also corresponded with leaders of national liberation movements throughout Africa and the world. I think publishing a selection of these correspondences will be of interest to anyone interested in the evolution of 20th-century resistance to Jim Crow and colonial subjugation.

As far as what makes the life and work of Hunton relevant today, I would say this: Hunton was a tremendously hard-working, self-sacrificing person who never sought the spotlight. According to every account that I’ve read, he was humble to a fault, unassuming, yet deeply committed to the day-to-day grunt work of building a movement strong enough to challenge racial capitalism domestically and internationally. His legacy is internationalist. And I think that, coupled with everything else, is probably the most relevant thing for activists today to learn about the life and work of Hunton. He clearly saw the need for international allies, particularly in the socialist camp, that were strong enough to compel concessions from world capitalism. And he didn’t waver from that conviction. This is an important lesson, a lesson worth studying.

Study the life and work of Alphaeus Hunton with these titles from International Publishers:

The Cancer of Colonialism: W. Alphaeus Hunton, Black Liberation, and the Daily Worker 1944-1946, by Tony Pecinovsky

Decision in Africa: Sources of conflict, by W. Alphaeus Hunton

Alphaeus Hunton: The Unsung Valiant, by Dorothy Hunton

Let Them Tremble: Biographical Interventions Marking 100 Years of the Communist Party USA, ed. by Tony Pecinovsky